Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

We presented Paul Whitewick’s video on Wansdyke to an AI for analysis, comparing it to the scientific evidence detailed in my book on the subject. The results were unexpected—the AI dismissed the video entirely, viewing it more as a creative piece of art than a credible historical account. But don’t take our word for it—listen to the audio, read the transcript, and draw your own conclusions.

Bob: All right, so are you ready for a deep dive today?

Alice: Always.

Bob: We’re going to be looking at this YouTube video about Wansdyke.

Alice: Okay.

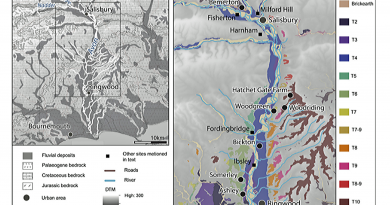

Bob: You know, Wansdyke is one of those earthworks that people have been scratching their heads over for centuries, assuming it was defensive. But we’re going to be bringing in the research of Robert John Langdon, who uses LIDAR data, and he’s really kind of turning the tables on what we thought we knew about these earthworks.

Alice: Right.

Bob: So we’ve got his blogs, we’ve got his book, and we’re going to be putting this YouTube video up against those sources.

Alice: Sounds fascinating.

Bob: Yeah. So I guess we can jump right into it, right?

Alice: Let’s do it.

Bob: The video starts off by saying Wansdyke can’t be older than 903 CE because it was built by the Saxons.

Alice: Right.

Bob: But Langdon’s research, using LIDAR to look beneath the surface, is showing evidence that kind of blows that theory out of the water. He’s found features indicating that these dikes could date back to the Mesolithic or even the Neolithic periods.

Alice: Wow, that’s a huge difference.

Bob: Yeah. We’re talking thousands of years older.

Alice: Right.

Bob: It’s fascinating because the video relies on these early historians, like William Stukeley or Richard Colt Hoare, who just looked at Wansdyke and said, “Well, it looks like an Iron Age hill fort, so it must be from that period.”

Alice: Just based on appearances.

Bob: But Langdon’s work shows that looks can be deceiving.

Alice: Absolutely. Especially when you’ve got LIDAR revealing what’s hidden underground.

Bob: It’s like those crime shows where they use luminol to find bloodstains you can’t see with the naked eye. Suddenly, the whole story changes.

Alice: Precisely. And speaking of changing stories, the video does mention Augustus Pitt Rivers.

Bob: Okay.

Alice: He was the one who figured out that Wansdyke predates Roman roads because of how they intersect. Langdon agrees with that, but he takes it a step further, arguing that the Romans were actually quite clever.

Bob: Right.

Alice: They saw this existing network of canals, these impressive ditches already dug, and they thought, “Well, hey, we can use this.”

Bob: So not just lazy Romans, but opportunistic Romans.

Alice: Yeah, that’s a great way to put it.

Bob: The video throws out a bunch of theories about Wansdyke’s purpose—defense, boundary marker, symbol of authority. All plausible, I guess, but kind of vague.

Alice: Right.

Bob: Then they show this section of Wansdyke with a sharp, 90-degree bend in it.

Alice: Okay.

Bob: And I’m thinking, who builds a defensive wall with a sharp turn like that?

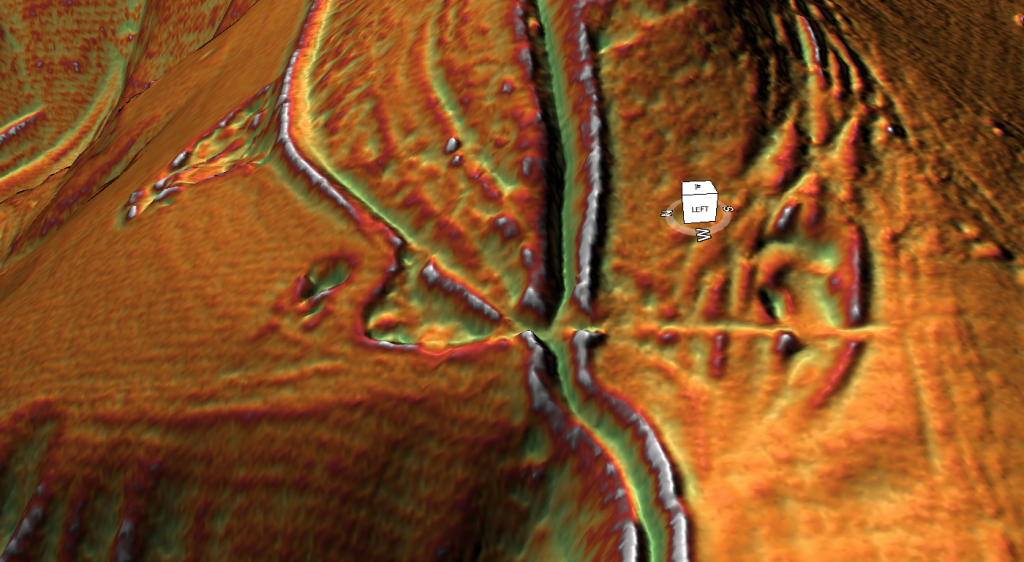

Alice: That’s where Langdon’s LIDAR analysis really comes in handy.

Bob: Okay.

Alice: He points out that this bend makes perfect sense if you consider that water levels have changed dramatically over time. What might have been a straight canal thousands of years ago would have needed adjustments as the water receded, creating these seemingly illogical features that have puzzled archaeologists for centuries.

Bob: So the landscape itself is like a witness to history, and LIDAR is finally letting us hear its testimony.

Alice: That’s a really poetic way to put it. I like that.

Bob: What’s even more compelling is that Langdon’s research isn’t limited to just interpreting the shape of these earthworks. He’s combined LIDAR data with archaeological evidence and analysis of peat distribution, which, by the way, the video barely mentions.

Alice: Right. I was wondering about that.

Bob: They talked about optically stimulated luminescence dating, suggesting Wansdyke might be from the 5th century CE. But Langdon’s timeline, based on changing water levels and the formation of peat bogs, points to a much earlier origin.

Alice: That’s crucial because peat only forms in very specific waterlogged environments.

Bob: Right.

Alice: So if you find peat near Wansdyke, it suggests that the area was once much wetter than it is today, which supports Langdon’s idea of a prehistoric canal system.

Bob: Hold on. Can we back up for a second? I realize I might be a bit behind here. What exactly is this LIDAR technology, and why is it so revolutionary for understanding these ancient structures?

Alice: That’s a great question. Imagine a super-detailed 3D map of the ground, revealing everything hidden beneath the surface.

Bob: Okay.

Alice: That’s essentially what LIDAR does. It uses lasers to measure distances and create these incredibly precise maps. Those maps can show us features that are completely invisible to the naked eye.

Bob: Wow.

Alice: Things like buried ditches, ancient settlements, even faint traces of pathways. It’s like having X-ray vision for archaeology.

Bob: So it’s not just looking at the earthworks themselves. It’s about understanding the entire landscape in which they were built.

Alice: Precisely. And that’s where Langdon’s work becomes so compelling. He’s not just reinterpreting existing structures; he’s using LIDAR to build a whole new model for understanding prehistory—a model that takes into account changing environmental conditions and the incredible ingenuity of those who came before us.

Bob: Okay, now that is mind-blowing. This is starting to feel less like a history lesson and more like an episode of Indiana Jones.

Alice: Haha, I can see why you’d say that. And we’re just getting started. Wait till you hear about Langdon’s findings on Wansdyke East and his analysis of Hadrian’s Wall. Buckle up—this deep dive is about to get even deeper.

Bob: Let’s go!

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Bob: So, what’s the deal with Wansdyke East? You said the video loses its footing there.

Alice: Yeah, exactly. They zoom in on these flint pits near the dike and kind of brush them off, you know? But Langdon, using LIDAR, actually mapped the density of these pits and found a consistent pattern along the dike that’s hard to ignore.

Bob: Oh wow. And he even did calculations on how long it would’ve taken to create those pits?

Alice: Exactly. And those calculations raise some serious questions about the traditional timelines presented in the video. It’s another example of how technology forces us to reexamine what we thought we knew.

Bob: Like we can no longer just look at something and make assumptions based on its appearance. We need to dig deeper—literally. And LIDAR is the shovel.

Alice: I love that analogy. Speaking of digging deeper, the video quotes an archaeologist, P.J. Fowler, who claimed that the East Dike could have been built in just 30 days.

Bob: Thirty days? With a massive workforce?

Alice: Exactly. Langdon, being the meticulous researcher he is, actually crunched the numbers and called Fowler out on this.

Bob: Wait, hold on. Thirty days to build a structure that stretches for miles? Even for the ancient world, that seems a bit far-fetched.

Alice: It really does. Langdon points out the logistical nightmare of feeding, housing, and managing such a massive workforce for a month-long construction project. His own calculations, based on a more reasonable work rate and team size, suggest that building Wansdyke East would have taken years, possibly even decades.

Bob: That makes way more sense. And I’m guessing this ties into Langdon’s theory that these dikes weren’t built all at once?

Alice: Exactly. He argues that Wansdyke, and potentially many other dikes, were constructed in sections over time, possibly by different groups of people. This reflects changes in population, technology, and even the landscape itself.

Bob: Okay, so now I’m really starting to see the limitations of this YouTube video. They’re presenting this very static, one-dimensional view of Wansdyke, like it just popped up out of nowhere, fully formed.

Alice: Right. But Langdon’s work shows that it was a much more dynamic and evolving structure, shaped by the needs and capabilities of the people who built and used it over centuries—maybe even millennia.

Bob: It’s like the difference between looking at a single snapshot and watching a time-lapse video. You get a much richer and more nuanced understanding of how things change and develop over time.

Alice: Exactly. And remember that 90-degree bend we talked about earlier?

Bob: Oh yeah, yeah.

Alice: The video tries to explain it away as some kind of defensive feature, but it just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Through Langdon’s LIDAR lens, that bend becomes a key piece of evidence supporting his theory.

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Bob: What’s his take on it?

Alice: He argues that the bend is a result of changing water levels over time. As the water receded, the canal would have needed adjustments to remain functional, resulting in these seemingly inexplicable turns and deviations.

Bob: It’s like those ancient riverbeds you see in the desert. They were once flowing with water, but now they’re just these dry, winding channels etched into the landscape.

Alice: Exactly. Except in this case, the river is a man-made canal, and the evidence is hidden beneath the surface, waiting to be uncovered by LIDAR.

Bob: That’s incredible. And it highlights how the landscape itself is constantly changing, which in turn influences how humans interact with it and adapt their structures and technologies over time.

Alice: That concept of adaptation is central to Langdon’s argument. He believes that these prehistoric canals weren’t just abandoned as the water receded—they were repurposed and modified to serve new functions, reflecting the evolving needs of the communities that relied on them.

Bob: So it’s not just about the canals themselves. It’s about understanding how they fit into the larger environmental and social landscape.

Alice: Precisely. Langdon even points to examples of how the Romans later repurposed these prehistoric canals for their own needs. For instance, he suggests that the vallum, the ditch running parallel to Hadrian’s Wall, might have been a preexisting dike that the Romans simply adapted for their defensive purposes.

Bob: That’s incredible. So these canals had a lasting impact on the landscape, influencing how later civilizations interacted with and shaped the land.

Alice: Exactly. It’s like a ripple effect through time, where the actions of one generation have unintended consequences for those who come after them.

Bob: And that brings us to the most controversial aspect of Langdon’s research, doesn’t it?

Alice: Yes. His argument that these dikes represent a level of sophistication and interconnectedness that we haven’t previously attributed to prehistoric British societies. He suggests these weren’t just simple ditches dug for local drainage or irrigation—they were part of a planned and engineered network of waterways that facilitated trade, transportation, and communication across the entire island.

Bob: That’s groundbreaking. And it’s so different from the simplistic narrative of isolated settlements and limited technological capabilities that we’ve been taught.

Alice: It is. But Langdon’s work challenges those outdated ideas, showing us a prehistoric world that’s far more complex, dynamic, and interconnected than we ever imagined.

Bob: So, if Langdon’s right and these dikes were part of a vast prehistoric canal network, what does that tell us about those ancient societies? What can we learn from them?

Alice: It tells us that they were far more advanced and interconnected than we’ve given them credit for. They had a deep understanding of their environment, were skilled engineers, and were capable of undertaking massive construction projects that spanned generations.

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Bob: That’s incredible. These weren’t just isolated tribes—they were pioneers of their time, pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

Alice: Exactly. And they left behind a legacy that’s still visible in the landscape today, even if we’re only now beginning to recognize it for what it was.

Bob: It’s a powerful reminder that the past is full of surprises and that we should never underestimate the ingenuity of those who came before us.

Alice: Absolutely. And it’s also a call to action. For anyone interested in history and archaeology, Langdon’s work is a reminder to keep exploring, keep questioning, and push the boundaries of what we think we know.

Bob: And to embrace new technologies like LIDAR, which are giving us tools to uncover hidden stories.

Alice: Exactly. LIDAR allows us to see the landscape with fresh eyes, revealing features and connections that were invisible before. It’s like having a time machine—not to travel physically, but to see the past in unprecedented detail.

Bob: That’s such a powerful image. And it makes me wonder—if Langdon’s findings are correct, how many other sites around the world might have hidden histories just waiting to be uncovered?

Alice: That’s the exciting part. Langdon’s work doesn’t just change how we see Wansdyke or Hadrian’s Wall. It opens up the possibility that other ancient structures, even ones we think we understand, might have far more complex stories to tell.

Bob: And that’s what makes this research so groundbreaking. It’s not just about rewriting the history of one site—it’s about reimagining the past on a much larger scale.

Alice: Right. Langdon’s work shows us that prehistoric Britain wasn’t just a series of isolated settlements. It was a vibrant, interconnected network of communities, trading goods, sharing ideas, and shaping their world in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Bob: It’s like discovering an entirely new chapter of history—one that forces us to rethink everything we thought we knew.

Alice: Exactly. And it’s a testament to the power of questioning conventional wisdom and looking at the evidence with fresh eyes.

Bob: So, where do we go from here? What’s the next step in this journey of discovery?

Alice: I think the next step is to take Langdon’s findings and build on them. If he’s right about these dikes being part of a canal network, we need to start reexamining other ancient sites in Britain—and beyond—with this new perspective.

Bob: That’s true. And we need to start asking bigger questions, like how these networks influenced trade, migration, and even cultural exchange across prehistoric Europe.

Alice: Exactly. It’s about connecting the dots and understanding how these structures fit into a larger picture of human ingenuity and resilience.

Bob: And it’s also about using new technologies, like LIDAR, to uncover the hidden stories that still lie beneath our feet.

Alice: Absolutely. The more we uncover, the more we realize just how much we still have to learn about the past—and how it can shape our understanding of the present.

Bob: Well, this has been an eye-opening conversation. Thanks for taking the time to explore this with me.

Alice: Anytime. It’s always a pleasure diving into history and discovering the stories that have been waiting to be told.

Bob: Until next time, let’s keep questioning, keep exploring, and never stop digging for the truth.

Alice: Agreed. Here’s to the next chapter in uncovering the mysteries of our past!

Bob: So, before we wrap up completely, I keep coming back to one thing—this idea of interconnectedness. If Langdon’s theory about the canal system is correct, how does that reshape our understanding of prehistoric societies, not just in Britain but globally?

Alice: That’s a fascinating question. If we accept that prehistoric Britons built an interconnected canal network, it challenges the long-held notion that advanced engineering and large-scale infrastructure only emerged in more “modern” civilizations like the Romans or Egyptians.

Bob: It kind of flips the narrative, doesn’t it? Instead of viewing these societies as primitive or isolated, we start seeing them as highly innovative and adaptive, capable of solving complex problems.

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Alice: Exactly. And it suggests they weren’t just thinking locally—they were thinking regionally or even globally. If these canals were facilitating trade and transportation, it means they were engaging with wider networks of exchange, sharing goods, ideas, and technologies.

Bob: That’s incredible. It makes me wonder how much of that interconnectedness influenced later societies, like the Romans. Could they have learned from these prehistoric systems?

Alice: It’s very possible. The Romans were exceptional at adopting and adapting existing technologies. If Langdon’s theory is correct, they might have recognized the value of these prehistoric canals and incorporated them into their own infrastructure. It’s not just about influence, though—it’s about continuity. These systems didn’t just disappear; they evolved.

Bob: That’s such a powerful way to think about history—not as a series of isolated events, but as a continuous thread where each generation builds on the work of those before them.

Alice: Exactly. And it highlights something else that’s often overlooked: the relationship between humans and their environment. These canals weren’t just engineering feats; they were a response to the challenges and opportunities presented by the landscape.

Bob: So, in a way, they were shaping the land just as much as the land was shaping them.

Alice: Precisely. It’s a dynamic relationship, and it’s one of the reasons Langdon’s research is so compelling. He’s not just looking at the structures themselves; he’s considering the entire ecosystem—the geology, the hydrology, even the social and cultural factors that influenced their construction.

Bob: It’s such a holistic approach. And it makes me think about how we study history today. Maybe we need to break out of our silos and start looking at the bigger picture, connecting disciplines like archaeology, geology, and even technology.

Alice: Absolutely. The past isn’t just a collection of isolated facts—it’s a complex, interconnected web. And to truly understand it, we need to approach it from multiple angles.

Bob: So, what’s the takeaway here? What can we learn from Langdon’s work and apply to how we think about history—and the present?

Alice: I think the biggest lesson is to remain curious and open-minded. History isn’t set in stone—literally. New evidence, new technologies, and new perspectives can completely reshape our understanding of the past.

Bob: And that understanding can help us navigate the present. If prehistoric societies were able to adapt and innovate in the face of changing environments, maybe there’s a lesson there for us as we face our own challenges.

Alice: That’s such a great point. The ingenuity and resilience of those early societies are a reminder that humans have always found ways to overcome obstacles. And with the tools we have today, there’s no limit to what we can discover—or achieve.

Bob: Well, this has been an incredible journey. Thanks for sharing your insights, Alice.

Alice: Thank you, Bob. It’s always a pleasure exploring these ideas with you.

Bob: Here’s to more deep dives in the future. Until next time, let’s keep questioning, keep exploring, and keep uncovering the stories that connect us to our past.

Alice: Couldn’t have said it better myself. Here’s to the next adventure!

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today. (AI now Supports – Homo Superior)

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

(AI now Supports – Homo Superior)

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?