Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

Discover the Truth Behind Offa’s Dyke – Groundbreaking New Evidence Unveiled

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 2025 Update

- 2.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 2.0.1.1 Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

- 2.0.1.2 1. Historic England’s Own Words

- 2.0.1.3 2. Confusion by Reuse

- 2.0.1.4 3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

- 2.0.1.5 4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

- 2.0.1.6 5. The Official Timeline

- 2.0.1.7 6. What This Means

- 2.0.1.8 7. A New Understanding

- 2.0.1.9 Conclusion

- 2.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 3 Author’s Biography

- 4 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 5 Further Reading

- 6 Other Blogs

Introduction

For centuries, Offa’s Dyke has been enshrined in history as one of Britain’s most significant earthworks, stretching over 200 miles from coast to coast, dividing England from Wales. Traditionally thought to be a defensive structure built by the Mercian King Offa in the 8th century, its true origins and purpose have remained a mystery. Now, with the release of “Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Offa’s Dyke,” new evidence has emerged that challenges this conventional narrative, shedding light on a more ancient and complex history.

This meticulously researched book by Robert John Langdon introduces fresh findings, particularly through the use of cutting-edge LiDAR technology. This first-ever comprehensive LiDAR survey of Offa’s Dyke has revealed structural details and landscape features that point to the dyke being far more than a simple medieval boundary. What if this massive earthwork, long believed to be a Saxon fortification, was in fact part of a prehistoric system of canals? Langdon’s revolutionary hypothesis is poised to change the way we view not only Offa’s Dyke but Britain’s ancient landscape as a whole.

One of the most striking revelations presented in the book is the sheer number of gaps in the dyke’s construction. Archaeologists have long puzzled over the 60% of Offa’s Dyke that appears incomplete, with gaps large enough for people to pass through easily. This new research proposes a radical solution to this mystery: Offa’s Dyke was not intended as a continuous defensive wall but was instead designed to function as part of a prehistoric canal system. The dyke’s ditches, rather than being solely defensive, could have been designed to channel water during a time when Britain’s landscape was dramatically different.

The book delves into the environmental conditions during the post-glacial period, illustrating how rising water tables and extensive flooding following the Ice Age could have supported such a canal system. Langdon’s “Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis” suggests that many of Britain’s so-called “earthworks” were in fact canals, used for transport and irrigation in a landscape dominated by water. Offa’s Dyke, along with other ancient dykes, may have once been part of a vast network of water channels used by prehistoric civilizations.

In support of this theory, “Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Offa’s Dyke” provides detailed hydrological analysis and case studies that explore how these canals could have functioned. The evidence points to an era when the water levels were significantly higher than today, allowing these canals to serve as essential transportation routes. With rivers much wider and faster flowing, the dykes could have been the key to traversing the landscape and managing resources.

Langdon’s work also touches on the architectural ingenuity of these prehistoric people. The book highlights how the construction of dykes took advantage of natural springs and rivers, using water management techniques that predate Roman engineering by millennia. This challenges long-held assumptions about the technological capabilities of prehistoric societies and underscores their sophisticated understanding of hydrology.

Perhaps most controversially, the book re-examines the dating of Offa’s Dyke. While traditionally attributed to the medieval period, this new evidence suggests that parts of the dyke could date back thousands of years earlier, to the Mesolithic or even Neolithic periods. This would place the construction of Offa’s Dyke firmly in prehistory, long before the reign of King Offa, and would suggest that the structure was repurposed by later civilizations.

What makes “Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Offa’s Dyke” so compelling is its reliance on scientific evidence. Through the use of LiDAR imaging, Langdon has been able to provide a more accurate and detailed survey of Offa’s Dyke than ever before. This technological advancement allows researchers to see the landscape as it was in prehistoric times, revealing features that had previously gone unnoticed and challenging the interpretation of this structure as merely a medieval boundary.

For history enthusiasts and professionals alike, this book offers a fresh perspective on an ancient monument that many thought they already understood. By revisiting Offa’s Dyke with a modern, scientific approach, Langdon opens up exciting new possibilities for understanding Britain’s ancient past. The implications of these findings are profound, not only for historians and archaeologists but also for anyone interested in the evolution of human societies and their interaction with the environment.

Yet, as time’s river winds, a reconsideration of conventional wisdom has emerged. The once unassailable truth, akin to the impregnable ramparts of the past, is now scrutinised anew. The continuous defensive rampart, upon closer inspection, reveals fissures, like the fault lines in the crust of the Earth. These fissures disrupt the seamless narrative, prompting the inception of a new theory – that of a ‘prehistoric canal’.

This theory, wrapped in a shroud of reassuring promise, advances the notion that these ancient earthen works bore witness to water rather than martial or border marker endeavours. An absence of battle-scorned remains amidst both the 22 miles of Wansdyke and the 177-mile stretch of Offa’s Dike leaves the battle-defence hypothesis marooned on a metaphorical island of scepticism. This realisation uncovers a new vista like a chisel, removing layers of misconception.

Yet, amidst this scholarly voyage, there remain islands of perplexity. The Dykes, replete with the scars of incompleteness, resist easy classification as boundary markers. Their emergence, akin to the appearance of constellations in the night sky, has defied logic’s grasp. The tendrils of mystery intertwined with questions that seem to emerge like apparitions: why do these boundary markers etch their beginning and end points upon the landscape without a warrant? The echo of this query resonates across epochs, unanswered.

A symphony of scepticism further crescendos when examining the geographic tapestry. In their silent proclamation of territorial dominion, these ‘border markers’ traverse excessive expanses. The grandeur of significant rivers, echoing the pulse of nature’s handiwork, stands as a more overt marker. The irony is stark: these markers, established over years, even decades, stand as silent witnesses to the past while their purpose is shrouded in ambiguity.

In the grand theatre of scholarship, these revelations are like light cast upon a darkened stage. The archaeologists, guardians of historical truths, have overlooked the symphony of 1500+ ‘other’ scheduled Dykes that grace the British realm. A profusion of these markers, strewn across uninhabited islands, punctuates this narrative of ‘Boundary Markers.’ The paradox of these silent sentinels adorning barren shores challenges the very essence of this notion.

In this intricate dance between the past and the present, the story of Offa’s Dyke and its ilk unfolds. Like a mosaic, it emerges piece by piece, forming patterns that intertwine reality and speculation. The journey, mirroring Bronowski’s belief in multidisciplinary exploration, invites us to ponder the landscapes of our ancestors, adorned with markers that whisper tales of ownership, defence, or something yet unfathomed. And in this contemplation, the spirit of inquiry, kindled by the enigma of Offa, mirrors the enduring legacy of those who seek understanding amid the mysteries of time.

Boundary Markers – A lesson in time

With their reliance on earthworks as territorial markers, the historical hypothesis surrounding land boundaries emerges as a thought-provoking inquiry. Yet, as we delve deeper into the evidence, a poignant need for more compelling proof becomes evident. Throughout history, societies have indeed relied on markers to delineate their domains, be they natural features like rivers or human-made constructs like hedgerows. The practicality and economy of such choices are undeniable, especially when contrasted with the labour-intensive and costly endeavour of constructing extensive ditches and banks.

In the case of the renowned Offa’s Dyke, a perplexing puzzle emerges. The border, at times, gracefully follows the course of a river, a logical and sensible demarcation. However, the sudden shift to an earthwork set behind the same river defies easy explanation. Such inconsistency leaves us questioning the premise of these earthworks as unequivocal markers. The presence of inexplicable gaps in the land border only deepens the enigma, raising further doubt about the validity of the hypothesis.

We must seek coherence and reason within any historical proposition. The current hypothesis falls short in offering a convincing rationale for this transition from river to earthwork, and it fails to address the glaring accessibility of the river as a natural and readily available boundary marker.(Wansdyke flipbook)

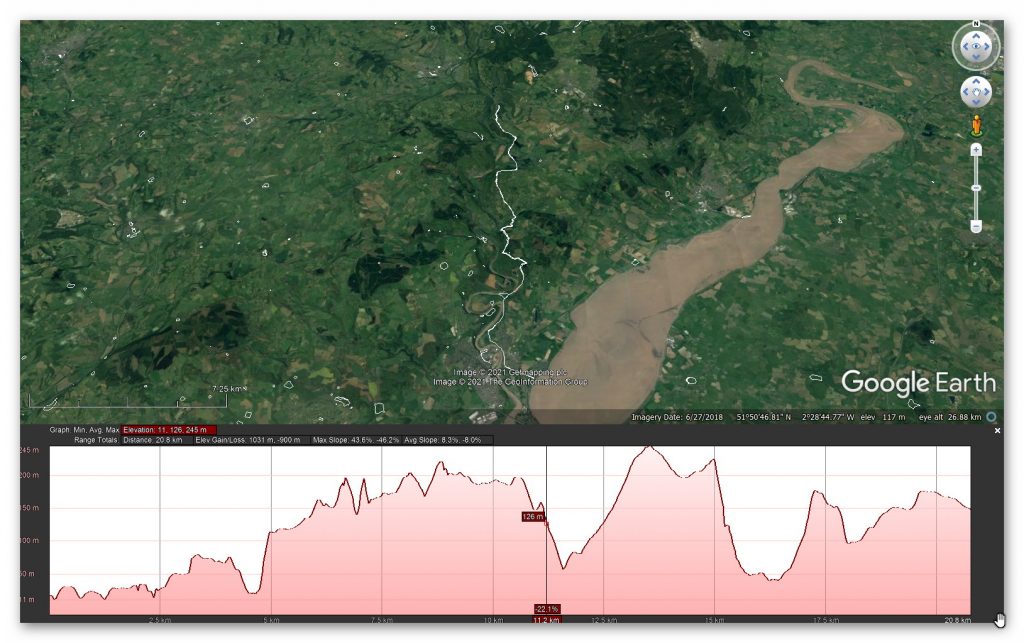

| Figure 2 – Path of Offa’s Dyke – showing its not remotely straight |

As we navigate the terrain of ancient earthworks, a commitment to rigorous scrutiny is paramount. Only by subjecting our hypotheses to relentless examination can we hope to uncover the authentic truths that lie obscured beneath the layers of time. In embracing a spirit of inquiry and humility, we may yet unlock the profound secrets of these age-old earthworks, shedding light on the intricate relationships between humanity and the landscapes they once inhabited. The pursuit of understanding is a journey marked by discovery and wonder, and in this voyage, we honour the legacy of those who once shaped the contours of history upon British soil.

Defensive Features

According to the pronouncements of esteemed Historical England, discerning the precise function of ancient boundaries proves to be an intricate endeavour. Whether they were intended for defence, stock-herding, or carrying symbolic significance remains elusive. In truth, most boundaries likely fulfilled a mosaic of roles, their purpose evolving and adapting over time. To presume that significant boundaries were solely for defence and smaller ones merely for livestock control would be an oversimplification of the intricate tapestry of history.

These artificial boundaries’ form, extent, and very existence offer vital clues, providing glimpses into their intended purposes. Additionally, their construction’s social and political context can provide insightful context. Yet, as we probe deeper into the historical narrative, it is evident that the written accounts primarily speak of Roman and Norman defence systems. With their ingenuity, the Romans devised the “ankle breaker” ditch – a V-shaped trench with a heightened counterscape masterfully designed to ensnare attackers or thwart mounted assailants.

These ingenious Roman ditches, predominantly surface near Roman sites, are conspicuously absent from 90% of excavations across Linear Earthworks. This absence challenges the prevailing hypothesis and prompts a reevaluation of past assumptions. In particular, investigations into Dykes such as Offa’s have uncovered an unsettling revelation – the defensive banks, in over 10% of the alignment, face the “wrong way.” This finding raises questions about the potential bias that may have influenced the support for this theory in the past.

As the archaeological landscape evolves, a shift is subtly underway, with many archaeologists quietly distancing themselves from this 20th-century hypothesis. The quest for truth demands unyielding inquiry, and as more mysteries come to light, the intricacies of ancient earthworks unfurl before our eyes. In the spirit of intellectual progress, we must approach each enigma with an open mind, ever eager to shed the limitations of preconceived notions and embrace the unfolding revelations of history.

2025 Update

Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

By The Prehistoric AI Team

For over a century, archaeologists have confidently told the public that Britain’s great linear earthworks—Offa’s Dyke, Wansdyke, and their lesser-known cousins—were “Saxon defensive boundaries.” Yet even the government’s own heritage body now quietly admits otherwise.

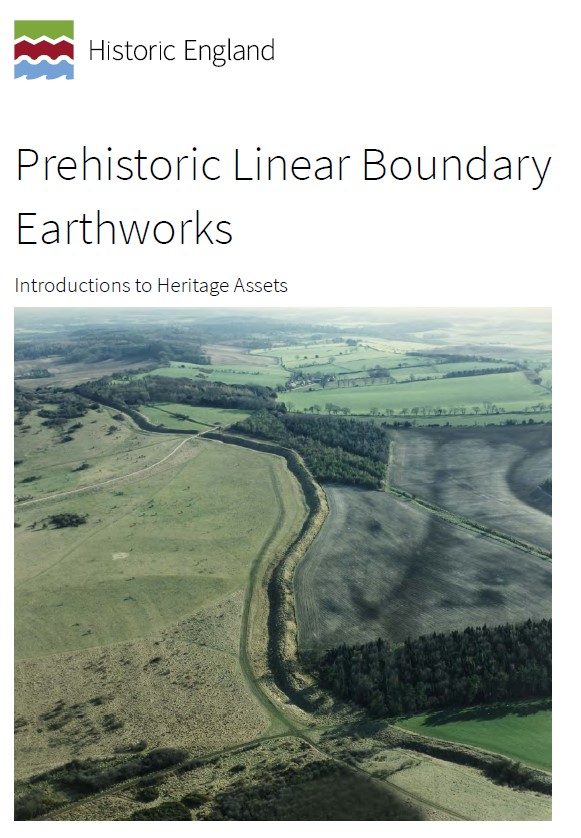

In its official publication HEAG 219: Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks (Historic England, 2018), the evidence is laid out in black and white: these monumental ditches and banks are not the product of medieval kingdoms but of prehistoric engineering, reaching back thousands of years before Offa or Rome.

1. Historic England’s Own Words

“From the Neolithic period onwards in the British Isles, natural boundaries such as watercourses and escarpments have been supplemented by artificial boundaries, often formed by a ditch and bank.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

That sentence alone demolishes the Saxon myth. These “artificial boundaries” appear from around 3600 BCE, the same period as Britain’s causewayed enclosures and early field systems.

“The earliest conventional linear earthwork so far confirmed, dating to around 3600 BC, follows the crest of the western escarpment of Hambleton Hill, Dorset, for perhaps as much as 3 km.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

In other words, the engineering tradition behind Offa’s and Wansdyke was already flourishing five thousand years earlier than the supposed Saxon period.

2. Confusion by Reuse

“Some of these early boundaries… continued to structure the social and economic landscape through the Iron Age and into the Roman period. Indeed, some have seen continuous use, or repeated re-use, from prehistory to the present day.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This statement is key.

What later archaeologists labelled as “Roman” or “Saxon” were often prehistoric earthworks re-used by later peoples. Defensive adaptations may have been made, but the physical structures already existed—centuries or millennia earlier.

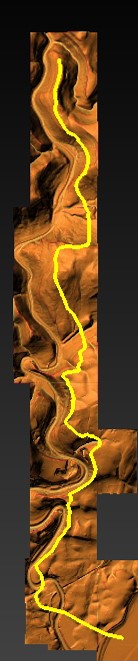

Langdon’s LiDAR analysis of Wansdyke and Offa’s Dyke shows this perfectly: continuous, water-connected segments, truncated by rivers and palaeochannels, betray origins in a hydrological engineering system, not a medieval frontier.

3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

“Prehistoric examples can be confused with medieval or later ones… Their form is not often diagnostic.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This rare confession from within Historic England supports Langdon’s long-standing criticism of archaeological dating methods. When earthworks lack carbonised deposits, dating often depends on surface finds—antler picks, pottery sherds, or even stray Roman coins—leading to circular logic.

As Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) argued, this flawed reasoning has turned prehistoric infrastructure into “Saxon defences” by default.

4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

“It is often difficult to determine whether a particular boundary was used for defence, for stock-herding, or purely as a symbol; in truth, most boundaries probably served all of these functions to varying degrees.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

The report concedes that no single explanation fits. The traditional defensive model collapses under scrutiny: there are no battle remains, no arrowheads, and no consistent rampart orientations.

This aligns with Langdon’s hydrological interpretation—seeing these earthworks as water management and navigation canals formed when Britain’s post-glacial landscape still retained a higher water table. Their engineering precision makes sense when viewed as prehistoric canalisation, not Saxon militarism.

5. The Official Timeline

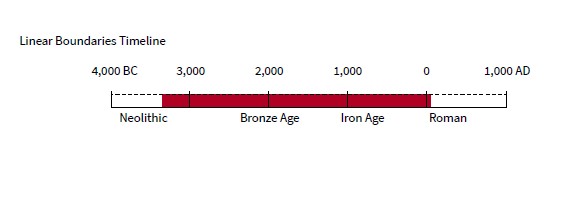

Historic England’s own chart places linear boundaries firmly in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, with only reuse continuing into later eras:

Linear Boundaries Timeline (HEAG 219, p.

4000 BC – Neolithic beginnings

1500 BC – Bronze Age expansion

0 AD – Roman reuse

The Saxon period doesn’t even feature.

6. What This Means

The implications are profound. Historic England has, perhaps unintentionally, validated the central premise of the Prehistoric Dyke Hypothesis:

Britain’s linear earthworks are prehistoric hydraulic and boundary systems, later adopted but not created by historical kingdoms.

The narrative of “Saxon kings digging 100-mile ditches by hand” finally collapses under the weight of its own impossibility—and the evidence from both LiDAR and the nation’s own heritage authority.

7. A New Understanding

The HEAG 219 publication is cautious in tone, but its data speaks volumes. The earliest linear boundaries coincide with the rise of complex water management systems, just as Langdon’s LiDAR work shows canal-like forms and river terminations.

It is time to update the textbooks:

Wansdyke, Offa’s Dyke, Car Dyke and their lesser cousins are prehistoric canals—part of a sophisticated hydrological network that once crisscrossed a flooded Britain.

Conclusion

Even Historic England now concedes that Britain’s linear earthworks belong to prehistory, not the Dark Ages.

By accepting this evidence, we move beyond folklore and into a genuinely scientific framework—one where landscape engineering, water management, and maritime trade define our ancestors’ genius.

Sources:

- Historic England (2018) Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks: Introductions to Heritage Assets (HEAG 219).

- Langdon, R.J. (2022) Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Wansdyke v1.2.

- Langdon, R.J. (2024) Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth.

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Statonbury Camp near Bath - an example of West Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Antonine Wall - Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Mesolithic Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Rivers of the Past were Higher – an Idiot’s Guide - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Extreme Weather & Ancient Subterranean Shelters - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Hoax - (Einkorn Wheat) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: Fact or Fiction? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Debunking the Media Misinterpretation of the "Black Stonehenge Builders" Reports - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Offa's Dyke (Chepstow) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's Giant Prehistoric Waterways - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Newgrange - Monument or Disneyland? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Wansdyke (4) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: From the Rhône to Wansdyke: The Case for a Standardised Canal Boat in Prehistoric Britain - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: 13 Things You Didn’t Know About Hillforts — The Real Story Behind Britain’s Ancient Earthworks - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Silbury Avenue - Avebury's First Stone Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon's Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain's First Monument - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Antler Pick Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnons - An Explainer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Case Study - River Avon - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Migration Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dykes Ditches and Earthworks - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Wansdyke Flipbook - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals - Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Problem with Hadrian's Vallum - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Solved - Pythagorean maths put to use four thousand years before he was born - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Caerfai Promontory Fort - Archaeological Nonsense - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's First Road - Stonehenge Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Stone Transportation Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Troy Debunked - Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeological 'pulp fiction' - has archaeology turned from science? - Prehistoric Britain