Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.0.1 Preconceived notions

- 1.0.2 The Subjectivity

- 1.0.3 The Case of Bluestonehenge: A Shift in Narrative Due to Contradictory Evidence

- 1.0.4 The Craig Rhos-y-Felin Quarry: Cherry-Picking Evidence to Fit a Hypothesis

- 1.0.5 Waun Mawn: The Search for a Lost Circle and the Limits of Peer Review

- 1.0.6 Conclusion: Moving Beyond the Illusion of Infallibility

- 2 Prologue

- 3 Further Reading

- 4 Other Blogs

Introduction

The peer-review system in archaeology is often regarded as a safeguard for academic integrity and quality control. However, it has become a gatekeeping mechanism that suppresses alternative interpretations and enforces conformity to prevailing theories. Michael Gordin, a historian of science, has noted that peer review is often mistaken for a flawless vetting system when, in reality, it is prone to bias and conservatism. He argues that the process tends to favour established paradigms, making it difficult for groundbreaking ideas to gain traction.

Archaeologist E. Thomas Lawson has pointed out that the peer-review system is highly susceptible to institutional biases. In a study published in Science and Technology Studies, Lawson demonstrated how reviewers often reject submissions that challenge dominant models, not necessarily based on weak evidence but because they disrupt the consensus. This issue is particularly acute in archaeology, where entrenched narratives about cultural evolution, settlement patterns, and technological development dominate scholarly discourse. Those who propose alternative chronologies or challenge the attribution of artefacts often find their work dismissed outright, regardless of its empirical rigour.

A stark example of this suppression can be seen in the case of the Cerutti Mastodon site in California. When Steven Holen and his team published their findings in nature in 2017, suggesting that humans may have been in North America over 130,000 years ago, the backlash was immediate. Critics did not merely question the dating methods; they dismissed the research as implausible despite using multiple independent dating techniques. This reaction illustrates how peer review often functions not as an objective filter but as a reinforcement of accepted timelines and theories, even when the evidence demands reconsideration.

Further, the peer-review system is primarily controlled by a small number of academic gatekeepers. A 2020 analysis by J. Scott Turner in The Journal of Scholarly Publishing revealed that many archaeological journals rely on a narrow pool of reviewers, many of whom share institutional affiliations and research backgrounds. This influence concentration creates an echo chamber where dissenting voices struggle to be heard. Turner’s study found that papers proposing unconventional interpretations had a rejection rate nearly three times higher than those aligned with mainstream archaeological views.

This lack of openness is compounded by the anonymous nature of peer review, which allows reviewers to dismiss or delay controversial findings without accountability. In some cases, reviewers have been found to recommend rejection of papers that later, when published through alternative means, proved to be groundbreaking. For instance, the discovery of pre-Clovis human presence in the Americas faced decades of dismissal until mounting evidence from sites like Monte Verde forced a reassessment of long-held beliefs. The delay in accepting such evidence highlights how peer review can be a brake on scientific progress rather than a facilitator of truth.

Another fundamental flaw of the peer-review system is its failure to recognise the evolving nature of scientific inquiry. History has shown that many discoveries initially rejected by the academic establishment later became widely accepted. The heliocentric model, continental drift, and the role of bacteria in ulcers were all dismissed before overwhelming evidence overturned the consensus. In archaeology, similar patterns emerge, where findings that contradict prevailing models are routinely discarded until the weight of evidence makes resistance untenable.

Archaeology must embrace a more open and transparent review process to foster true scientific progress. Double-blind peer review, in which authors and reviewers remain anonymous, could help mitigate personal and institutional biases. Additionally, encouraging post-publication peer review—where studies are critiqued and refined after publication rather than being blocked before dissemination—would allow for a more dynamic and evidence-driven discourse. Greater interdisciplinary collaboration, incorporating fields such as genetics, geophysics, and AI-assisted analysis, could also help challenge entrenched assumptions and promote a more balanced evaluation of new findings.

If archaeology aims to uncover the truth about the past, then the discipline must acknowledge and address the limitations of its review system. Suppressing dissenting ideas only delays the inevitable reevaluation of flawed theories. By reforming the peer-review process to prioritise empirical validity over academic orthodoxy, archaeology can become a more dynamic and self-correcting field that genuinely pursues knowledge rather than merely defending existing paradigms.

Preconceived notions

The peer-review process stands as a cornerstone of modern scientific inquiry, intended to filter research, uphold quality, and ensure the validity of published findings. It is a system whereby experts in a particular field critically evaluate a submitted manuscript before it is accepted for publication, ideally identifying flaws, inconsistencies, and errors. While the intention behind peer review is laudable, the assumption that all peer-reviewed papers are inherently accurate and devoid of error is a dangerous oversimplification. Particularly within archaeology, where interpretation plays a significant role and definitive proof can be elusive, placing unwavering faith in the peer-review stamp can hinder progress and perpetuate flawed narratives. The provided sources offer compelling insights into the limitations of peer review in archaeology, highlighting instances where the process has failed to prevent the dissemination of questionable findings, often due to the inherent subjectivity of the field and a tendency to prioritise the reporter’s preconceived notions over objective facts.

The investigations surrounding the dating and origins of Stonehenge, particularly the peer-reviewed publications stemming from Mike Parker-Pearson’s (MPP) work on Bluehenge, the bluestone quarries and Waun Mawn, serve as stark examples of how the peer-review system can be flawed and how its weight of evidence can be unduly influenced by the author’s reputation and desired outcomes. The case of Bluestonehenge further highlights how prior assumptions can drive research conclusions, even when contradictory data exists. These cases illustrate a broader issue within archaeology: a tendency to align findings with prevailing theories rather than rigorously testing hypotheses against all available evidence.

The Subjectivity

Unlike the hard sciences that rely on quantifiable data and reproducible experiments, archaeology frequently deals with fragmented evidence requiring interpretation. Archaeological findings are often unique to specific sites and cannot be replicated. This reliance on interpretation opens the door to interpretative bias, where an archaeologist’s perspective, cultural background, or theoretical framework can influence the narrative constructed from the available evidence. Consequently, the peer reviewers, who are also subject to their own biases, may inadvertently endorse interpretations that align with prevailing theories or the author’s established viewpoint rather than rigorously scrutinising the factual basis of the claims.

This can lead to “possibilities are often presented as certainties, creating a misleading view of the past.” The “establishment’s over-reliance on ‘peer review’ as a conformity standard of credibility” has been criticised, with Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, suggesting that peer review is merely a “crude means of discovering the acceptability—not the validity—of a new finding.” This crucial distinction underscores that peer review may often reinforce existing paradigms within the archaeological community, potentially hindering the acceptance of genuinely novel or contradictory evidence.

The Case of Bluestonehenge: A Shift in Narrative Due to Contradictory Evidence

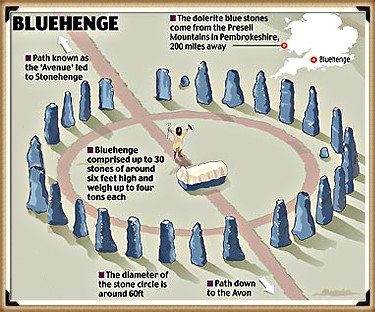

The first site to consider, Bluestonehenge, was under excavation in 2009. At that time, MPP was preparing to announce it as his bluestone site and believed it predated Stonehenge Phase I. However, the author of The Stonehenge Enigma (2013) raised concerns about this dating during their meeting. Based on his research of the surrounding 50 sites around Stonehenge and his post-glacial flooded environment hypothesis, they pointed out that Bluestonehenge would have been below water during the Neolithic period due to the River Avon remaining flooded.

MPP dismissed this research and published, but later carbon dating confirmed this point and supported the author’s hypothesis, as it is now accepted that Bluestonehenge was constructed between 2840–2230 BCE, which falls into the Early Bronze Age rather than the Neolithic period as initially proposed by MPP. This raises significant concerns about the reliability of peer-reviewed interpretations, as the initial dating—endorsed by peer review—was later found to be incorrect.

The Craig Rhos-y-Felin Quarry: Cherry-Picking Evidence to Fit a Hypothesis

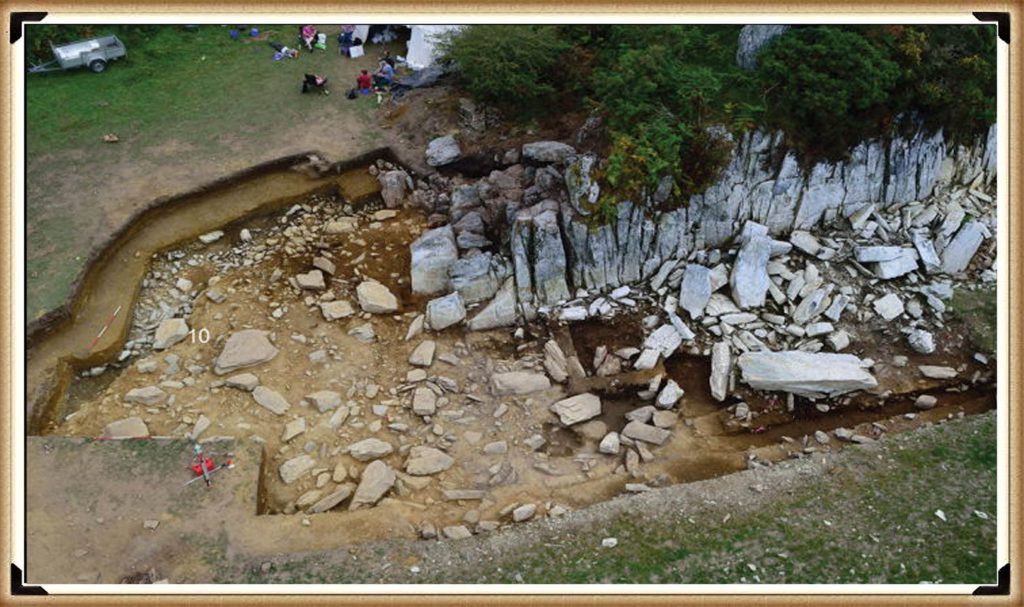

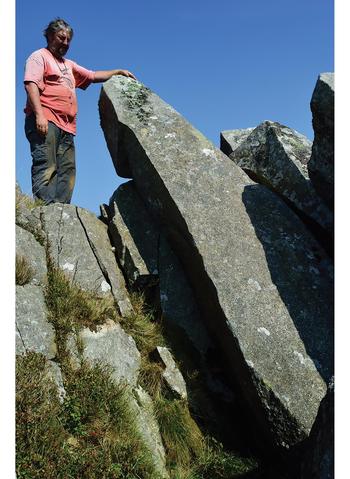

The investigations led by MPP into the origins of Stonehenge’s bluestones provide a compelling case study of how the peer-review process can be intertwined with pursuing a specific hypothesis, potentially overlooking contradictory evidence and leading to flawed conclusions. The initial breakthrough of finding the bluestone quarry at Craig Rhos-y-Felin was significant. However, the subsequent attempts to date the quarry and link it definitively to a specific construction date for Stonehenge, particularly around 3300 BCE, demonstrate a tendency to “attempt to find a date that would vindicate their Stonehenge dating methods.”

At Craig Rhos-y-Felin, over 42 carbon dates were obtained. However, the peer-reviewed reports emanating from this investigation were criticised for emphasising only a couple of Neolithic dates that appeared to support the 3300 BCE hypothesis while mainly overlooking the “extensive evidence found in the site’s man-made hearths, which showed that the quarry was first occupied in the Mesolithic Period.” These Mesolithic hearths, dating significantly earlier than the desired Neolithic timeframe, presented a challenge to the pre-existing narrative but were seemingly marginalised in pursuing a specific conclusion. This selective presentation of data, which the sources label as “clear ‘cherry-picking’ of the archaeological evidence,” suggests that the weight of the reported evidence was skewed by the author’s desire to validate a prior claim and that the peer-review process in this instance, did not sufficiently challenge this biased interpretation.

Waun Mawn: The Search for a Lost Circle and the Limits of Peer Review

The discrepancy between the desired 3300 BCE date and the slightly earlier dates obtained at the quarry site fueled the hypothesis of a “Welsh prototype stone circle which was moved 500 years later.” This second claim by MPP and subsequent peer-reviewed papers and TV programmes “claimed to find this ‘mysterious site,’ later to discover that it was nonsense raises serious questions about the rigour of the research and the extent to which the peer-review process scrutinised these evolving and ultimately unsubstantiated claims.

At Waun Mawn, only four bluestones were found, leading to a “sad attempt to fit a square peg into a round hole” by identifying ten further stone holes and guesstimating the existence of the remaining stones needed to match Stonehenge. Furthermore, the dating evidence from Waun Mawn is heavily criticised. While the program highlighted a single OSL date that appeared to align with the desired timeframe, the sources reveal that “there was not one OSL sample taken but 18, which gave results in the range of 6980+/- 2120 BCE to AD 1900 +/- 20.” The fact that “17 dating samples did not verify MPP’s Hypothesis, ONLY a single one,” strongly suggests a selective emphasis on a single data point to support a pre-existing claim.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond the Illusion of Infallibility

While the peer-review process remains a vital component of archaeological scholarship, it is crucial to recognise its inherent limitations and avoid believing that all peer-reviewed papers are accurate and error-free. The case studies surrounding Mike Parker-Pearson’s investigations into the origins of Stonehenge highlight how the subjectivity of archaeological interpretation, the pursuit of pre-existing hypotheses, and the potential influence of the reporter’s authority can lead to the publication of flawed findings. The selective use of data, the downplaying of contradictory evidence, and the development of speculative theories underscore the need for a more critical engagement with peer-reviewed publications, prioritising rigorous examination of the factual evidence and methodologies employed rather than relying on perceived authority.

Prologue

Archaeological research, while often considered a rigorous discipline, faces challenges concerning the reach and reliability of its published work. Studies have shown that a significant portion of academic papers receive minimal attention post-publication. Approximately 44% of all published manuscripts are never cited, indicating that nearly half of these works remain largely unread or unreferenced within the scholarly community.

Furthermore, citation analyses reveal that the average number of citations per paper is below ten. Achieving ten or more citations places a manuscript in the top 24% of the most cited works worldwide, underscoring the limited engagement many papers receive.

Regarding the accuracy of scientific publications, the rate of retractions has seen a notable increase. Although retracted papers still constitute a small fraction—under 0.1%—of the more than 25 million papers indexed in PubMed since the 1940s, this uptick highlights ongoing concerns about the reliability of published research.

In the realm of archaeology, the prevalence of flawed studies is challenging to quantify precisely due to the field’s interpretative nature and the scarcity of replication studies. However, documented cases, such as the Himalayan fossil hoax involving Vishwa Jit Gupta, illustrate that significant errors and even fraudulent activities can persist undetected for extended periods, thereby influencing subsequent research.

These insights emphasize the necessity for heightened scrutiny and critical engagement within archaeological scholarship to ensure the integrity and impact of its contributions.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.(Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: All Is Not Golden In Archaeology – theoarch