13 Things You Didn’t Know About Hillforts — The Real Story Behind Britain’s Ancient Earthworks

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.0.1 1. Hillfort Classifications Are Outdated and Over-Simplified

- 1.0.2 2. The “Fortress” Definition Has Stuck For Too Long

- 1.0.3 3. Hillforts Were Around Before the Iron Age

- 1.0.4 4. Population Growth Doesn’t Match the Fortress Theory

- 1.0.5 5. Hillforts Were NOT Evenly Distributed — Which Defies Pure Defence Logic

- 1.0.6 6. Little Evidence of Warfare or Prolonged Occupation

- 1.0.7 7. Danebury Hillfort Is Probably Older and Less “Fortress” Than Thought

- 1.0.8 8. Maiden Castle’s Massive Size Was Logistically Impossible to Defend

- 1.0.9 9. Maiden Castle’s “Massacre” Is Much Less Clear-Cut Than Popular Tales

- 1.0.10 10. Old Sarum Is Misunderstood as a Hillfort

- 1.0.11 11. Many Hillforts May Have Been Waterborne Trade Hubs, Not Forts

- 1.0.12 12. Economic Evidence Contradicts Military Function

- 1.0.13 13. Hillforts Were Multifunctional Community Centres

- 2 Conclusion

- 3 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 4 Further Reading

- 5 Other Blogs

Introduction

Hillforts have long been cast as the mighty defensive bastions of prehistoric Britain, iconic symbols of Iron Age tribal warfare and territorial defence. But if you peel back the layers of archaeological evidence, a very different, far more complex picture emerges. While some hillforts were adapted for military use during later periods—particularly during Roman expansion—the majority were multifunctional hubs serving economic, ceremonial, territorial, and social roles rather than purely defensive purposes.

Below, we unravel 13 surprising facts that challenge the traditional fortress narrative, shedding light on the true nature of hillforts across Britain and Ireland. Prepare to rethink what you thought you knew.

1. Hillfort Classifications Are Outdated and Over-Simplified

For nearly a century, archaeologists have tried to neatly categorize hillforts based on size, location, rampart construction, and age. Early scholars like Sir Mortimer Wheeler and later Barry Cunliffe developed classification schemes grouping hillforts into types such as early hilltop enclosures over 10 hectares, smaller settlements of 1–3 hectares, early univallate forts, and more complex multivallate sites. These categories aimed to make sense of the diversity by assigning function and status, often equating larger or more complex sites with defensive importance.

However, these classifications are increasingly questioned because they lean heavily on limited physical evidence and overlook the social and economic functions of these sites. For example, a large enclosure doesn’t necessarily mean a military fortress; it could be a ceremonial gathering place or a centre for trade. Likewise, a simple earthwork might have deep ritual significance rather than being a mere settlement defence. This simplified framework risks distorting the true roles these structures played in prehistoric societies.

By focusing too much on size and fortification features, scholars have missed the multifunctional nature of hillforts. Archaeological evidence now points to a more nuanced understanding: these sites often combined social, economic, political, and ritual functions alongside occasional defensive adaptations. We must therefore treat traditional categories with caution and embrace complexity.

2. The “Fortress” Definition Has Stuck For Too Long

The classical definition of a hillfort, as “a fortified refuge or defended habitation on elevated ground,” still dominates textbooks and popular understanding. Wikipedia and many reference works place hillforts squarely in the Bronze or Iron Age and depict them as military installations designed to control territory and repel attackers. Their defining features are steep earthworks, ramparts, palisades, and ditches, strategically placed to take advantage of high ground.

While this definition neatly fits some later hillforts, it oversimplifies a wide array of prehistoric enclosures that often lack convincing military architecture or evidence of warfare. Moreover, it ignores that many of these sites have much older origins, with some showing continuity of use stretching back thousands of years before the Iron Age, into the Neolithic or even Mesolithic periods. The persistence of this fortress-centric view obscures the diverse social realities of prehistoric communities.

Holding on to this entrenched definition restricts archaeological interpretation and public perception. It encourages viewing hillforts as relics of constant warfare rather than appreciating their complex social, ceremonial, and economic dimensions. The reality, as recent research shows, is far richer and more varied.

3. Hillforts Were Around Before the Iron Age

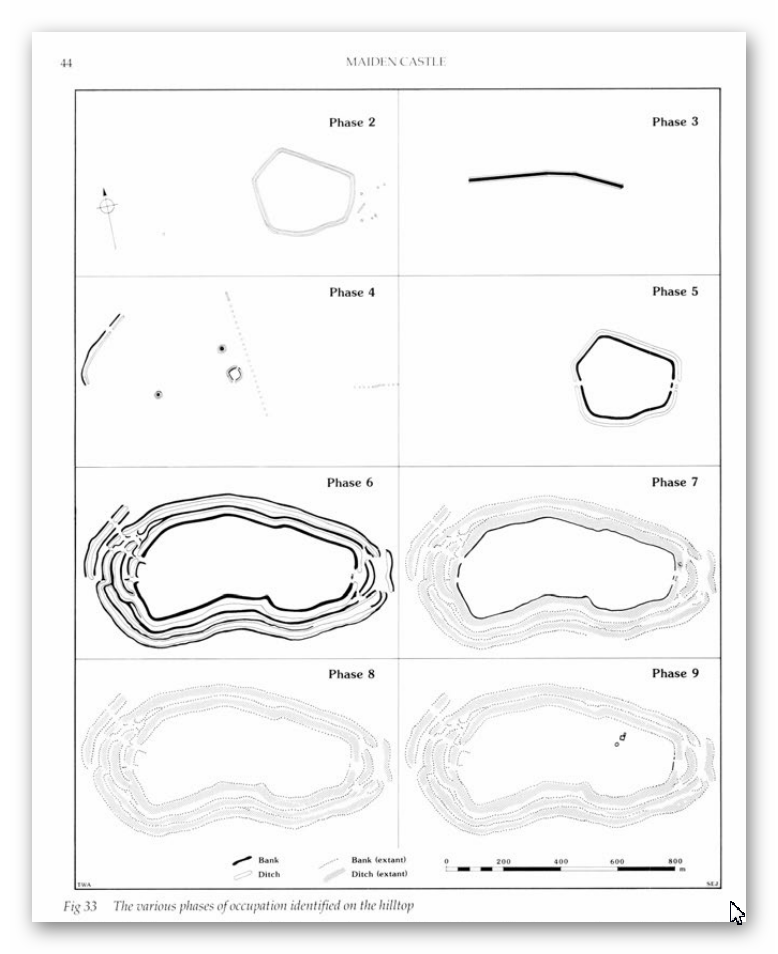

Many people associate hillforts exclusively with the Iron Age, roughly 800 BC to AD 43 in Britain. However, extensive excavations reveal that numerous hillforts have earlier origins, dating back to the Late Bronze Age and even Neolithic times. Cultures such as the Urnfield (1300–750 BC), Hallstatt (1200–500 BC), and La Tène (600 BC–50 AD) saw the proliferation of hillforts, but the groundwork was laid much earlier.

For instance, archaeological layers in famous sites like Maiden Castle and Danebury contain flint tools and pottery shards from the Neolithic and Mesolithic eras. This pushes back their initial construction or use by several millennia before the traditionally accepted Iron Age period.

This deep time depth challenges the fortress narrative by suggesting many hillforts began as community or ritual centres long before any significant tribal warfare. Their repeated reuse over thousands of years indicates multifunctional importance beyond defence and highlights the continuity and adaptation of prehistoric societies.

4. Population Growth Doesn’t Match the Fortress Theory

Prehistoric Britain’s population dynamics don’t quite fit with the idea of a landscape littered with defensive forts. Estimates suggest that during the Neolithic (circa 5000 BC), Europe’s population hovered between 2 and 5 million. By the Late Iron Age, it had swelled to roughly 15 to 30 million. But except for dense pockets like Greece and Italy, most settlements in Britain were small, often supporting fewer than 50 people.

Hillforts stand out as exceptions, accommodating communities as large as 1,000, but such numbers were rare. The later appearance of oppida—urban centers housing up to 10,000—reflects increasing societal complexity. However, the distribution and density of hillforts do not correlate with an equally dense, heavily militarized population needing constant defense.

The logistical challenge of defending thousands of these hillforts, each requiring a substantial population of warriors and support staff, becomes apparent when population estimates are compared to fort numbers. There simply weren’t enough people to maintain standing armies or garrisons in every hillfort, undermining the fortress theory.

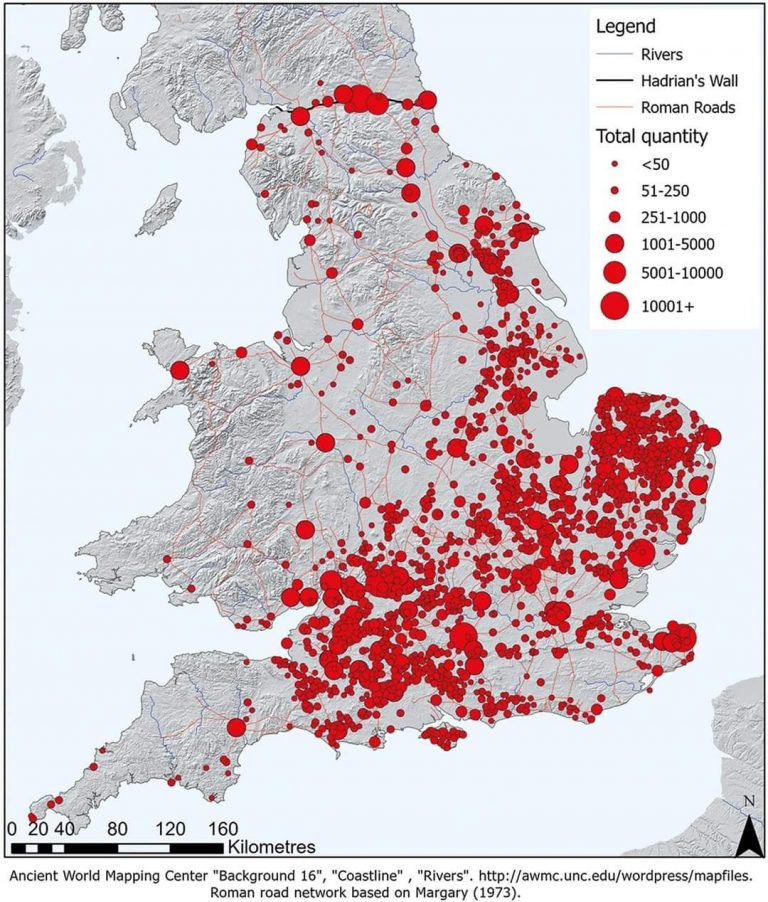

5. Hillforts Were NOT Evenly Distributed — Which Defies Pure Defence Logic

If hillforts were purely defensive, you’d expect them to be evenly spaced, strategically located to guard borders or resources. But the reality is messier. Over 3,300 hillforts are clustered unevenly across the British Isles. Take the Isle of Man—a tiny island of 572 square kilometres—with an astounding 32 hillforts. That’s roughly one hillfort every 5 to 6 square kilometres, far too dense to be defensible or necessary purely for military protection.

Additionally, about 30% of hillforts hug coastlines, with another 50% near prehistoric river systems. This heavy concentration around water suggests that control of waterways, trade, and communication routes were important considerations. Another 70% are near quarrying or resource extraction zones, linking hillforts to economic activity rather than just defense.

Such distribution patterns are inconsistent with a landscape dominated by warring tribes guarding fixed territories. Instead, they imply hillforts functioned as hubs for trade, social interaction, resource management, and ritual gatherings tied closely to natural and economic landscapes.

6. Little Evidence of Warfare or Prolonged Occupation

If hillforts were military bastions, we would expect abundant archaeological evidence of sustained occupation, such as permanent housing, weapon caches, and clear defensive structures like palisades or gatehouses. We would also expect to find mass graves or layers of debris from sieges.

Yet, surprisingly, few hillforts show such evidence. Many have signs of only episodic or seasonal occupation. Archaeologists rarely find weapons stockpiles or large-scale battle remains inside hillforts. Defensive architectural features are often minimal or absent, and many ditches have shapes inconsistent with fortification—flat-bottomed, not steep and V-shaped.

This absence of clear martial evidence points to alternative interpretations: hillforts served multiple roles, perhaps acting as gathering places for trade, ritual ceremonies, or political meetings, with defense being a secondary or occasional function.

7. Danebury Hillfort Is Probably Older and Less “Fortress” Than Thought

Danebury in Hampshire is often cited as a classic Iron Age hillfort, extensively excavated by Barry Cunliffe in the 1970s. While traditionally dated to the 6th century BC and used for about 500 years, recent carbon dating and flint finds suggest it began as a Late Bronze Age stock enclosure 3,000 years ago. Some evidence even points to Neolithic or Mesolithic origins.

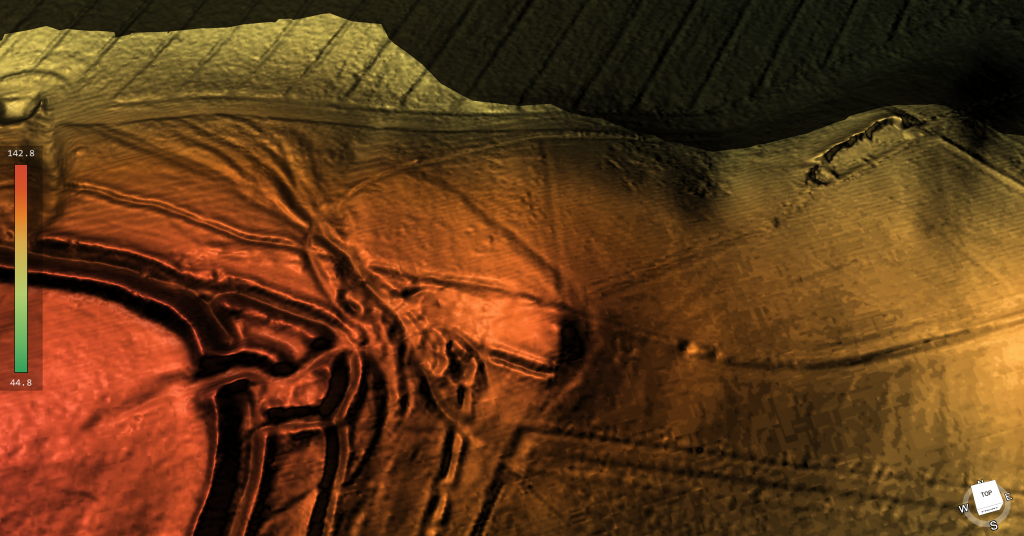

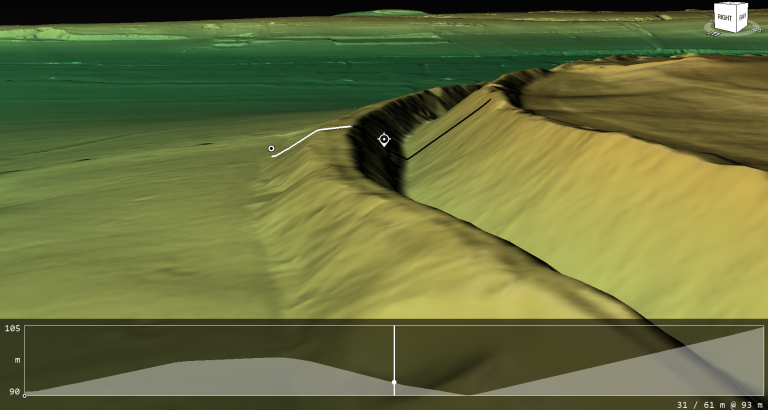

Excavations uncovered thousands of flints spanning multiple prehistoric periods, alongside Beaker pottery, challenging the notion that Danebury was a purely Iron Age military installation. Furthermore, LiDAR technology revealed a linear earthwork or dyke connected to the fort’s outer ditch—possibly a prehistoric waterway—hinting that Danebury might have been linked by boat transport rather than isolated on a hilltop.

Its ditches have soil deposited mostly on the outside rather than the inside, contradicting standard defensive designs. Together, these facts point towards Danebury functioning as a multifunctional site, involved in trade and social activities, rather than solely as a fortress.

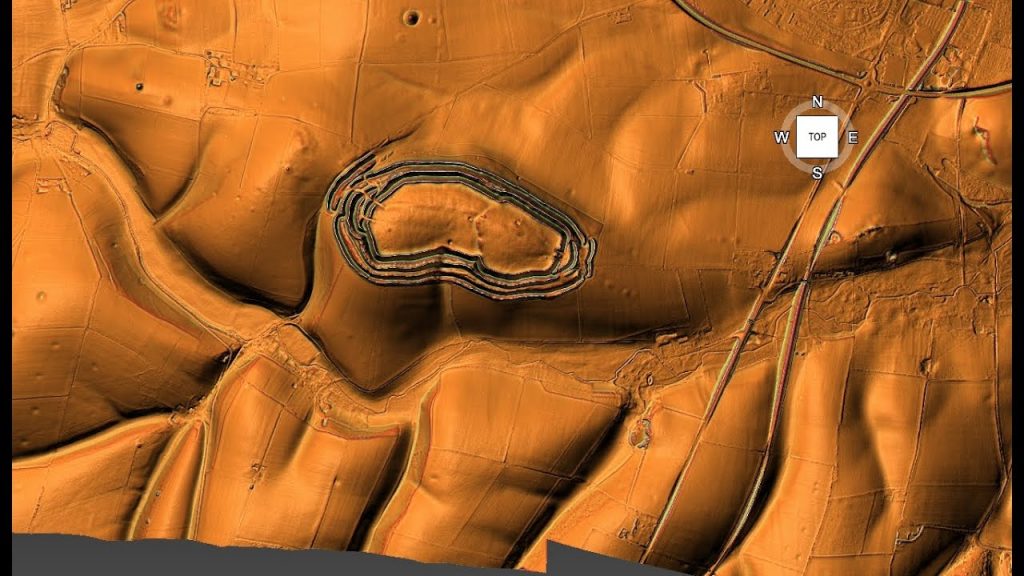

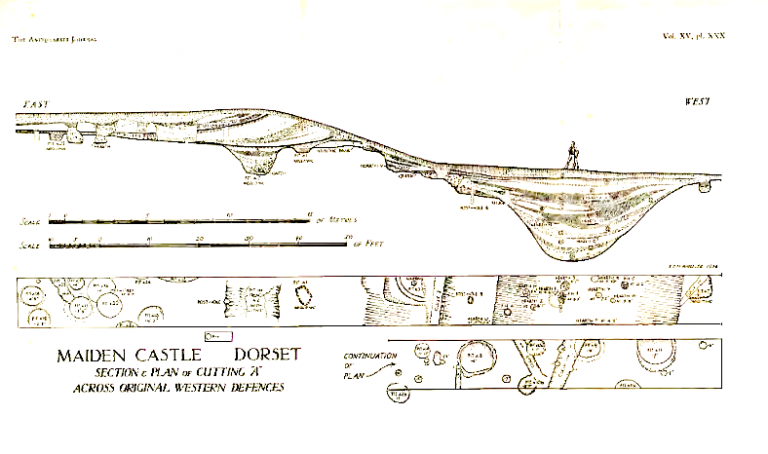

8. Maiden Castle’s Massive Size Was Logistically Impossible to Defend

Maiden Castle in Dorset is Britain’s largest hillfort, sprawling over 47 hectares. This sheer size would require an enormous number of defenders—estimates suggest 155 soldiers per shift, totaling around 465 to cover 24-hour protection. That’s not counting support personnel, families, and provisions.

Feeding and supplying such a large garrison would be a monumental task. Monthly food needs would include vast amounts of grain and meat, requiring extensive storage, pastureland for livestock (around 516 animals per month), and water—at least 15 deep wells, supplying almost 750,000 litres monthly. Yet, archaeological digs and LiDAR surveys reveal only a handful of residential structures and no evidence of such water management infrastructure.

Additionally, no workshops or industrial sites capable of producing weapons and armour at scale have been found. This logistical void casts serious doubt on the idea that Maiden Castle was a continuously manned military fortress rather than a large social or ritual centre.

9. Maiden Castle’s “Massacre” Is Much Less Clear-Cut Than Popular Tales

Popular accounts sometimes describe Maiden Castle as the site of a Roman siege massacre. However, excavations found only a handful of burials near entrances, with no mass graves or battlefield debris layers typical of large-scale violence.

Among the burials were an adult male with a debated projectile wound, a young woman with trauma signs, and several children—not typical combatants. Most bodies showed no direct evidence of violent death.

Over 20,000 slingstones discovered near entrances might suggest defensive stockpiles, but their purpose could also be ritualistic or related to hunting. After the supposed Roman attack, the site was largely abandoned, implying that its defensive role, if any, was limited and temporary.

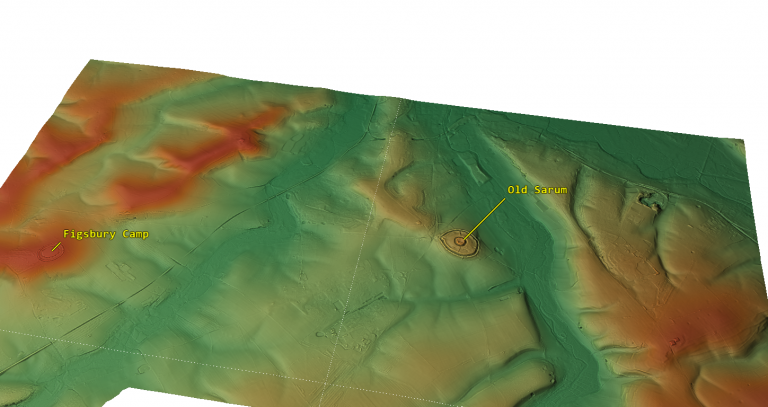

10. Old Sarum Is Misunderstood as a Hillfort

Old Sarum, located in Wiltshire, is often labeled an Iron Age hillfort established around 400 BC. It later became a Roman fort and then a medieval castle site. However, its position on a floodplain island, not a prominent hill, challenges the traditional fortress narrative.

Claims of Roman roads converging there have been questioned by LiDAR and satellite data, which show no clear road leading to Bath or elsewhere. The earthworks around Old Sarum appear more consistent with water management or moated enclosures than defensive ditches. Soil spoil was found mostly outside ditches, suggesting construction to hold water rather than repel enemies.

11. Many Hillforts May Have Been Waterborne Trade Hubs, Not Forts

Some hillfort ditches and earthworks may have functioned as prehistoric moats or canals, filled naturally due to higher ancient water tables or artificially to facilitate boat traffic. This suggests hillforts could have been accessible by water, acting as trading hubs connected through river networks.

LiDAR scans reveal links between earthworks and ancient waterways, highlighting a landscape adapted for waterborne movement rather than isolated hilltop defense. This theory fits with the frequent coastal and riverine siting of hillforts and their association with quarry and resource sites.

12. Economic Evidence Contradicts Military Function

True military sites like Roman forts show dense economic footprints: lost coins, markets, bathhouses, workshops, and dense habitation. Hillforts lack this. Coins are extremely rare even after coinage was common. There are no permanent markets or large public buildings supporting garrisoned troops.

Instead, hillforts yield evidence of seasonal occupation: animal enclosures, storage pits, and sparse artefacts, reflecting episodic use for trade, social gatherings, or ritual. This economic silence is a strong indicator that hillforts were not permanent military bases but multifunctional social centres

.

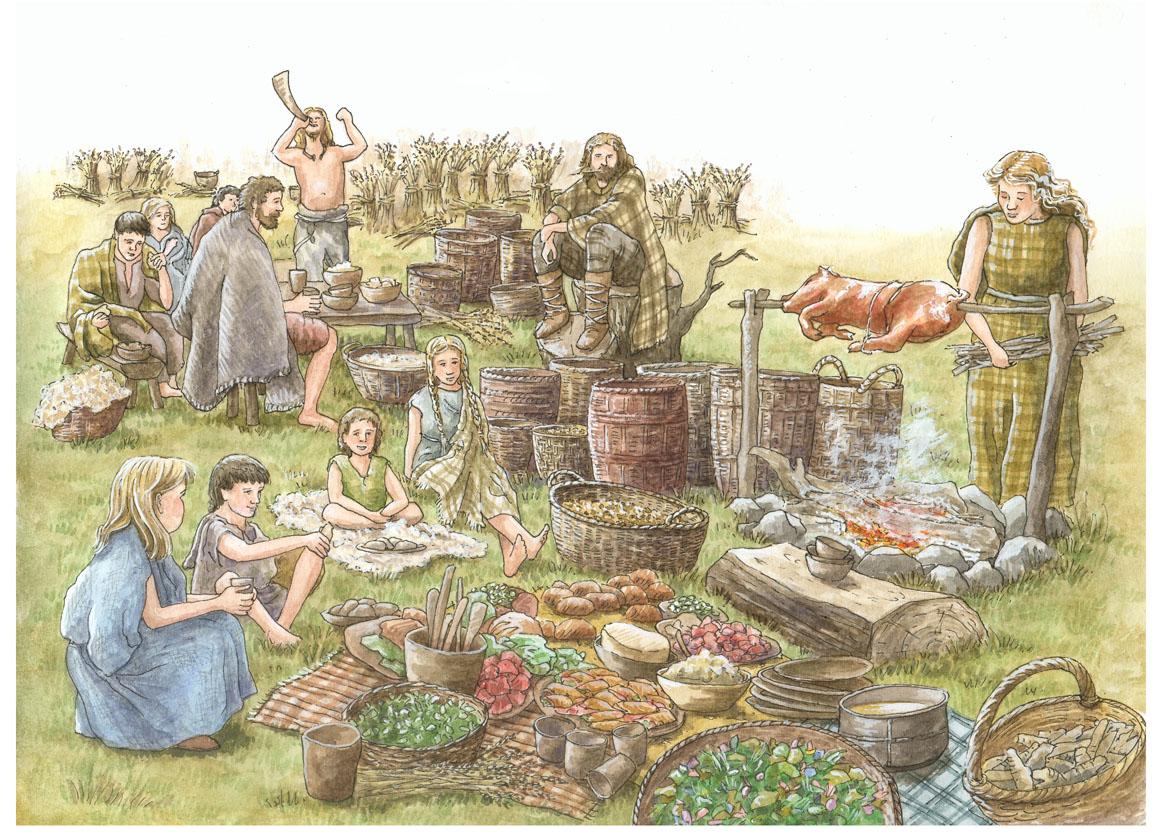

13. Hillforts Were Multifunctional Community Centres

All evidence points toward hillforts as dynamic, multifunctional hubs where prehistoric communities gathered seasonally for trade, political negotiation, rituals, and resource management. Defense may have been a later addition or an occasional function but was rarely the primary purpose.

Their diverse roles challenge the simplistic “fortress” label and invite us to rethink prehistoric Britain as a complex network of interconnected social landscapes, not a battlefield scattered with defensive works.

Conclusion

With new dating methods, LiDAR technology, and detailed excavations, the “hillfort as fortress” idea no longer holds water. We need to embrace a broader, richer understanding of these sites as centers of ancient community life, economy, and ritual.

What Archaeology Must Prove To Call Hillforts “Forts”.

To keep the “fort” label credible, archaeologists must find:.

Large permanent residences and housing clusters.

Reliable water supplies (wells, cisterns).

Dense loss of coins and trade items.

Associated civilian settlements outside gates.

Evidence of workshops making weapons and armor.

Defensible gatehouses and ramparts designed for battle.

Layers showing repeated conflict or siege trauma.

So far? – Those lines of evidence are mostly absent.

Final Thought.

Hillforts aren’t just relics of ancient warfare — they’re dynamic social landscapes, hubs of economy, ritual, and community. It’s time to move beyond outdated militaristic views and embrace their true complexity.

As the saying goes:

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence — and calling hillforts ‘forts’ without it is no longer credible archaeology.”

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

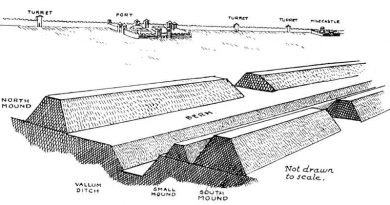

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?