Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.0.1 1. Car Dyke Holds Water – The Unignored Proof

- 1.0.2 2. It Was Found With a Boat Inside – Proving Its Role in Trade

- 1.0.3 3. It Predates the Saxons – By Millennia

- 1.0.4 4. It Has a Gradient – But No Locks

- 1.0.5 5. It Follows the Water Table – Not Defensive Terrain

- 1.0.6 6. It’s Not Fortified, Defended, or Manned

- 1.0.7 7. It Connects Economic Zones – Not Battlefields

- 1.0.8 8. Engineers Recognise It as a Canal – Historians Don’t

- 1.0.9 9. LiDAR Shows It Was Designed to Flow – And Modified Over Time

- 1.0.10 10. It’s Ignored Because It Breaks the Narrative

- 1.0.11 Conclusion: The Earthwork That Should Rewrite British History

- 2 Update 2025

- 2.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 2.0.1.1 Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

- 2.0.1.2 1. Historic England’s Own Words

- 2.0.1.3 2. Confusion by Reuse

- 2.0.1.4 3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

- 2.0.1.5 4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

- 2.0.1.6 5. The Official Timeline

- 2.0.1.7 6. What This Means

- 2.0.1.8 7. A New Understanding

- 2.0.1.9 Conclusion

- 2.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 3 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 4 Further Reading

- 5 Other Blogs

Introduction

For a ditch that still carries water and once carried boats, Car Dyke gets shockingly little mention in mainstream archaeology. That’s not just curious—it’s catastrophic for the credibility of those who claim to interpret Britain’s prehistoric and early historic earthworks.

Because if one linear ditch turns out to be a working canal with measurable gradient, scientific dating, cargo evidence, and no locks—then maybe, just maybe, the whole Saxon “defensive ditch” fantasy collapses.

Here are 10 undeniable reasons why Car Dyke demands to be the centrepiece of any earthwork debate—and why ignoring it is a damning indictment of both academia and the clickbait content crowd.

1. Car Dyke Holds Water – The Unignored Proof

For once, we have a dyke that still holds water thousands of years later, and yet it’s been largely ignored by archaeologists. Why? Because even the establishment has been forced to admit it’s at least Roman—centuries before the Saxons ever arrived. That single fact alone should have sent shockwaves through every earthwork discussion in Britain.

But it gets worse (for them). Unlike other so-called dykes that are little more than dried-up crop lines or eroded ridges, Car Dyke actively carries water today—without pumps or modern maintenance. And it does so by using natural hydrology: it tracks springs, palaeochannels, and contours. The water isn’t a fluke. It’s engineered.

Modern canals struggle with long-term viability. Victorian ones break down in less time than it took Car Dyke to outlive them. This canal-that-shouldn’t-be is the empirical smoking gun that makes the entire “defensive ditch” theory look like child’s play.

2. It Was Found With a Boat Inside – Proving Its Role in Trade

Let’s state this plainly: a boat was found at the bottom of Car Dyke, carrying cargo from Horningsea. Not just wood and planks, but a Roman boatload of traded pottery. That isn’t some blurry interpretation of post-holes or hypothetical “ritual deposits.” That’s a working freight canal in action.

And it didn’t run flat like a modern canal. It had gradient. Yet the boat moved through it. That alone busts another myth: the idea that a canal must be flat or filled with locks to function. Car Dyke shows us that early canal systems could operate on natural slope and hydrological flow using primitive yet effective methods—like controlled weirs or paddles.

This isn’t just a quirky detail. This is the central truth about Britain’s forgotten transport systems: they were real, they worked, and they predate every medieval myth people still cling to.

3. It Predates the Saxons – By Millennia

Mainstream archaeology likes to box Car Dyke neatly into the “Roman period.” But a closer look—combining LiDAR, hydrology, artefact stratigraphy, and even water table analysis—suggests something much older. The gradient-following route, the lack of Roman lock systems, and the natural watercourse integration all imply prehistoric origins.

In fact, English Heritage acknowledges that many of the 1,500+ dykes across Britain are Bronze Age in date. That means dyke-building was not a Saxon invention, nor a Roman one. It was native. Indigenous. Advanced. And older than most academic models are comfortable with.

So why is Car Dyke constantly excluded from earthwork discussions? Because it’s the inconvenient truth—the one that doesn’t fit the narrative. Once you admit Car Dyke isn’t Saxon or military, you have to rethink every other dyke in Britain. And that’s a step too far for those defending century-old academic assumptions.

4. It Has a Gradient – But No Locks

Canals are supposed to be flat. Everyone learns this. Or if not flat, then stepped with locks. But Car Dyke defies this rule—and yet it still flows. It has elevation change, yet no locks. How is this possible?

Because Car Dyke was built with hydrology in mind. The route follows springs and contours, allowing gravity to do the work. Springs feed the canal from higher terrain, and water flow was likely managed by weirs or primitive paddle systems—not mechanical locks, which came much later.

This isn’t a fringe theory. It matches what early Victorian canals used before locks became standard: regulated flow control and spring-fed energy. If anything, Car Dyke shows an understanding of natural slope engineering that historians have simply failed to credit. It’s time we stop assuming locks were needed in the ancient world just because modern canal textbooks say so.

5. It Follows the Water Table – Not Defensive Terrain

A defensive ditch should, by all logic, run along strategic high points—ridges, lookouts, and natural chokepoints. But Car Dyke doesn’t. It meanders across the lowlands, carefully hugging springs, ancient riverbeds, and the contour lines of the landscape.

This isn’t bad planning—it’s brilliant hydrological design. LiDAR shows that Car Dyke tracks the natural flow of groundwater, which itself follows fractal branching patterns through subsurface geology. Car Dyke’s course mirrors these patterns, routing water efficiently through what was once a wet, navigable landscape.

This is not accidental. It’s proof that the builders understood how water behaves—and designed accordingly. That’s not military engineering. That’s environmental infrastructure.

6. It’s Not Fortified, Defended, or Manned

There are no ramparts, no towers, no palisades, no weapon caches—nothing you would expect from a genuine defensive installation. No manning posts. No tactical vantage points. No evidence of military occupation. And that’s because Car Dyke was never meant to be defended—it was meant to be used.

From a tactical perspective, its location makes no sense as a defence. It skirts lowland terrain and wetland—areas easy to bypass and of no strategic advantage. If the Romans or Saxons wanted a defensive line, they’d have built it on the ridge, not in the marsh.

Worse still for the defensive theory, it’s too wide and too shallow to serve as an obstacle. Even a half-asleep raiding party could hop across it or walk through it in summer. But make it a watercourse? That makes sense. That width is perfect for flat-bottomed boats. The shallow slope is ideal for managing flow.

What Car Dyke does reflect is infrastructure—something designed to move goods, manage water, and possibly serve agricultural or trade needs. That historians still pitch it as a defensive barrier is an act of historical negligence, not interpretation.

This wasn’t built to repel enemies. It was built to connect people and places.

7. It Connects Economic Zones – Not Battlefields

Car Dyke was not laid out to repel invaders—it was laid out to move goods, grain, pottery, and people. It aligns with known Roman and prehistoric economic zones. To the south lies Cambridge, a well-documented production centre for Roman pottery and agricultural goods. To the north, Lincoln, a vital Roman city that was both a military and trading hub.

The dyke itself snakes through productive Fenland, tapping into river systems and lowland routes that allowed flat-bottomed boats to access key distribution points. It would have enabled the bulk movement of resources from inland production areas out to the east coast or across to the Midlands.

This is not a defensive line—it’s a commercial highway. And unlike other dykes where claims of military use are based on guesswork, Car Dyke gives us empirical evidence: a cargo boat, pottery cargo, and intact hydrology.

It is the model for a prehistoric logistics network—the ancient motorway of its time. To call it a “ditch” is like calling the M1 a gravel track.

8. Engineers Recognise It as a Canal – Historians Don’t

Ask a canal engineer and they’ll tell you: Car Dyke behaves exactly like a canal. From slope gradients to spring-fed input points, from embankment reinforcements to flow behaviour—it’s textbook hydrological infrastructure. Ask a historian or archaeologist? You’ll hear about Saxons, boundaries, and “ritual significance.” One profession is using data. The other, stories.

And here’s where the real divide shows: today’s historians and weekend explorers often walk along hilltop trails and look at steep embankments thinking they’re seeing military architecture. But they’re not seeing the landscape as it was. At the time of construction, these earthworks were surrounded by dense tree cover, underbrush, and a waterlogged landscape. The environment was radically different.

Even modern OS maps reinforce the illusion. They plot the route, not the physical banks and ditches that still survive—or don’t. Many supposed linear features on these maps are conceptual rather than empirically verified.

Moreover, the romantic idea of canal boats drifting lazily through the countryside couldn’t be further from reality. These weren’t pleasure routes. They were brutally practical, engineered for moving heavy goods. Boatmen would often walk the banks, using ropes or animals to haul their cargo over gradients. They weren’t passengers—they were hauliers. The canal was a tool, not a scenic journey.

Car Dyke is a functioning piece of industrial infrastructure—not a footnote to Saxon folklore. The fact that engineers see this clearly while historians do not says everything.

9. LiDAR Shows It Was Designed to Flow – And Modified Over Time

LiDAR mapping doesn’t just confirm that Car Dyke was engineered for water flow—it reveals a dual-phase design that evolved over time. The original sections, which appear as meandering, contour-following paths, reflect prehistoric engineering that closely follows natural watercourses and groundwater patterns. These early routes were likely laid out to access spring heads and maintain gentle gradients through undulating terrain.

Later, the Romans stepped in—not to replace—but to enhance this existing network. They added straighter, more engineered segments, likely to improve water flow through marshier areas and create more direct connections between economic zones. These upgrades demonstrate Roman pragmatism in adapting and augmenting older infrastructure rather than erasing it.

This dual-phase model—prehistoric ingenuity coupled with Roman adaptation—makes Car Dyke a layered landscape of evolving technology. And it serves as a model for reinterpreting other earthworks that may also bear hidden complexities beneath the topsoil. LiDAR makes that possible.

10. It’s Ignored Because It Breaks the Narrative

Car Dyke is the archaeological elephant in the room. It ticks all the boxes that should make it central to our understanding of Britain’s ancient infrastructure—yet it’s nowhere to be found in major discussions about linear earthworks. Why?

Because it’s a narrative breaker. It doesn’t fit the Saxon-defence myth that academics have repeated for generations. It doesn’t have ramparts, it wasn’t built on a ridge, and it didn’t separate warring kingdoms. It carried water, not warriors.

To accept Car Dyke as a canal is to accept that Wansdyke, Offa’s Dyke, and hundreds of other dykes may also be misunderstood. That would mean admitting that archaeology has mislabelled key monuments for decades—if not centuries.

So instead, they ignore it. They avoid referencing it in academic journals. They leave it off comparative studies. They don’t teach it in the university curriculum. Because if Car Dyke is real—and it demonstrably is—then the whole Saxon-centric model starts to unravel.

This isn’t just avoidance. It’s archaeological malpractice.

Conclusion: The Earthwork That Should Rewrite British History

Car Dyke isn’t an exception—it’s the control sample. The reference point. The benchmark. It proves that prehistoric and Roman Britain had the engineering skill and hydrological knowledge to construct vast canal systems without locks, without pumps, and without our modern assumptions.

It demolishes the false dichotomy that dykes are either Saxon boundary markers or defensive trenches. It demands that we revisit every linear earthwork in Britain through the lens of empirical data, not inherited theory.

This isn’t just about one canal—it’s about how we do archaeology. About valuing physical evidence over folklore. About admitting when we’ve been wrong—and finally starting to get it right.

Car Dyke still holds water. But can our institutions?**

Update 2025

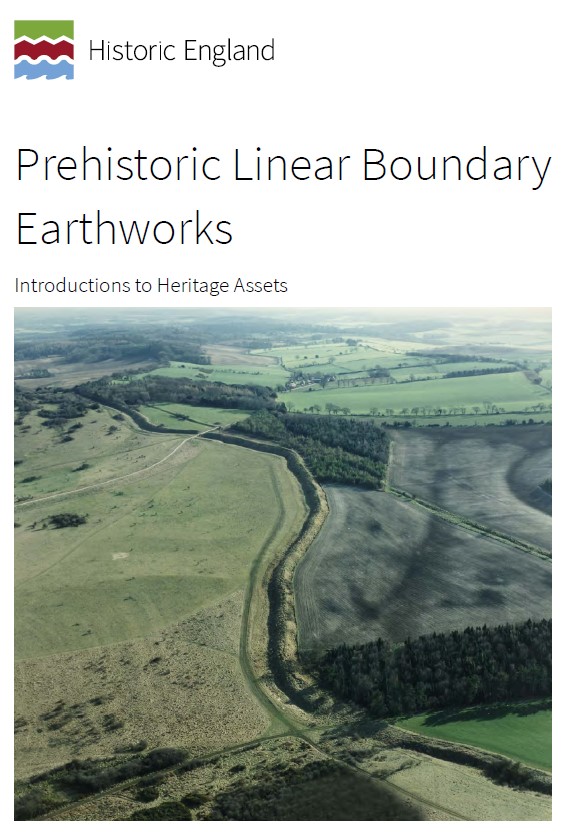

Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

By The Prehistoric AI Team

For over a century, archaeologists have confidently told the public that Britain’s great linear earthworks—Offa’s Dyke, Wansdyke, and their lesser-known cousins—were “Saxon defensive boundaries.” Yet even the government’s own heritage body now quietly admits otherwise.

In its official publication HEAG 219: Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks (Historic England, 2018), the evidence is laid out in black and white: these monumental ditches and banks are not the product of medieval kingdoms but of prehistoric engineering, reaching back thousands of years before Offa or Rome.

1. Historic England’s Own Words

“From the Neolithic period onwards in the British Isles, natural boundaries such as watercourses and escarpments have been supplemented by artificial boundaries, often formed by a ditch and bank.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

That sentence alone demolishes the Saxon myth. These “artificial boundaries” appear from around 3600 BCE, the same period as Britain’s causewayed enclosures and early field systems.

“The earliest conventional linear earthwork so far confirmed, dating to around 3600 BC, follows the crest of the western escarpment of Hambleton Hill, Dorset, for perhaps as much as 3 km.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

In other words, the engineering tradition behind Offa’s and Wansdyke was already flourishing five thousand years earlier than the supposed Saxon period.

2. Confusion by Reuse

“Some of these early boundaries… continued to structure the social and economic landscape through the Iron Age and into the Roman period. Indeed, some have seen continuous use, or repeated re-use, from prehistory to the present day.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This statement is key.

What later archaeologists labelled as “Roman” or “Saxon” were often prehistoric earthworks re-used by later peoples. Defensive adaptations may have been made, but the physical structures already existed—centuries or millennia earlier.

Langdon’s LiDAR analysis of Wansdyke and Offa’s Dyke shows this perfectly: continuous, water-connected segments, truncated by rivers and palaeochannels, betray origins in a hydrological engineering system, not a medieval frontier.

3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

“Prehistoric examples can be confused with medieval or later ones… Their form is not often diagnostic.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This rare confession from within Historic England supports Langdon’s long-standing criticism of archaeological dating methods. When earthworks lack carbonised deposits, dating often depends on surface finds—antler picks, pottery sherds, or even stray Roman coins—leading to circular logic.

As Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) argued, this flawed reasoning has turned prehistoric infrastructure into “Saxon defences” by default.

4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

“It is often difficult to determine whether a particular boundary was used for defence, for stock-herding, or purely as a symbol; in truth, most boundaries probably served all of these functions to varying degrees.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

The report concedes that no single explanation fits. The traditional defensive model collapses under scrutiny: there are no battle remains, no arrowheads, and no consistent rampart orientations.

This aligns with Langdon’s hydrological interpretation—seeing these earthworks as water management and navigation canals formed when Britain’s post-glacial landscape still retained a higher water table. Their engineering precision makes sense when viewed as prehistoric canalisation, not Saxon militarism.

5. The Official Timeline

Historic England’s own chart places linear boundaries firmly in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, with only reuse continuing into later eras:

Linear Boundaries Timeline (HEAG 219, p.

4000 BC – Neolithic beginnings

1500 BC – Bronze Age expansion

0 AD – Roman reuse

The Saxon period doesn’t even feature.

6. What This Means

The implications are profound. Historic England has, perhaps unintentionally, validated the central premise of the Prehistoric Dyke Hypothesis:

Britain’s linear earthworks are prehistoric hydraulic and boundary systems, later adopted but not created by historical kingdoms.

The narrative of “Saxon kings digging 100-mile ditches by hand” finally collapses under the weight of its own impossibility—and the evidence from both LiDAR and the nation’s own heritage authority.

7. A New Understanding

The HEAG 219 publication is cautious in tone, but its data speaks volumes. The earliest linear boundaries coincide with the rise of complex water management systems, just as Langdon’s LiDAR work shows canal-like forms and river terminations.

It is time to update the textbooks:

Wansdyke, Offa’s Dyke, Car Dyke and their lesser cousins are prehistoric canals—part of a sophisticated hydrological network that once crisscrossed a flooded Britain.

Conclusion

Even Historic England now concedes that Britain’s linear earthworks belong to prehistory, not the Dark Ages.

By accepting this evidence, we move beyond folklore and into a genuinely scientific framework—one where landscape engineering, water management, and maritime trade define our ancestors’ genius.

Sources:

- Historic England (2018) Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks: Introductions to Heritage Assets (HEAG 219).

- Langdon, R.J. (2022) Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Wansdyke v1.2.

- Langdon, R.J. (2024) Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?