Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

Introduction

When most people hear “Ogham,” they think of mysterious notched stones scattered across Ireland and parts of Britain, their edges lined with cryptic strokes. Officially, these are understood as memorial inscriptions in an early form of the Irish language, a belief held with confidence by most archaeologists and linguists. (Rethinking Ogham)

But what if that story isn’t the whole picture?

What if the origins of Ogham lie not in phonetic language at all, but in something far older and more practical: a tally system?

The Standard Interpretation: A Memorial Script

According to the established view, Ogham was developed around the 4th century AD to write Primitive Irish. It was primarily carved onto standing stones as commemorations of individuals or as boundary markers, with inscriptions typically reading something like: “X, son of Y.”

This interpretation is strongly supported by:

- Bilingual stones with both Ogham and Latin texts.

- Consistent grammatical patterns.

- Repetition of personal and tribal names.

It appears cut and dry—until you step back and ask a deeper question:

Why did this script evolve this way, using notches and strokes, rather than borrowing from the Latin alphabet already available nearby?

The Tally Hypothesis: Origins in Counting and Resource Tracking

Across ancient societies, the earliest writing systems often began as counting tools. Cuneiform in Mesopotamia, for example, started with tally marks and tokens representing quantities of grain or livestock. Why not consider that Ogham may have followed a similar path?

Here’s what supports the tally origin hypothesis:

- Visual resemblance: Ogham characters look remarkably like tally marks grouped in fours and fives—just like traditional wooden tally sticks used well into the Middle Ages for accounting.

- Function before language: In pre-literate societies, marking ownership, trade quantities, or taxation might have required a visual record long before the need for recording names arose.

- Boundary markers: Some Ogham stones stand alone in landscapes, with no clear burial or commemorative context. Were these stones not honouring a person, but marking how many cattle passed or how much land was measured?

- Isolated or partial inscriptions: Several stones contain only a few characters that don’t translate clearly into names or words. These could represent quantities, symbols, or shorthand codes rather than phonetic text.

Stone as Currency and the Role of Stone Circles in Trade

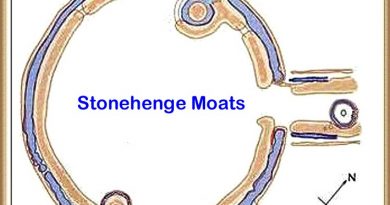

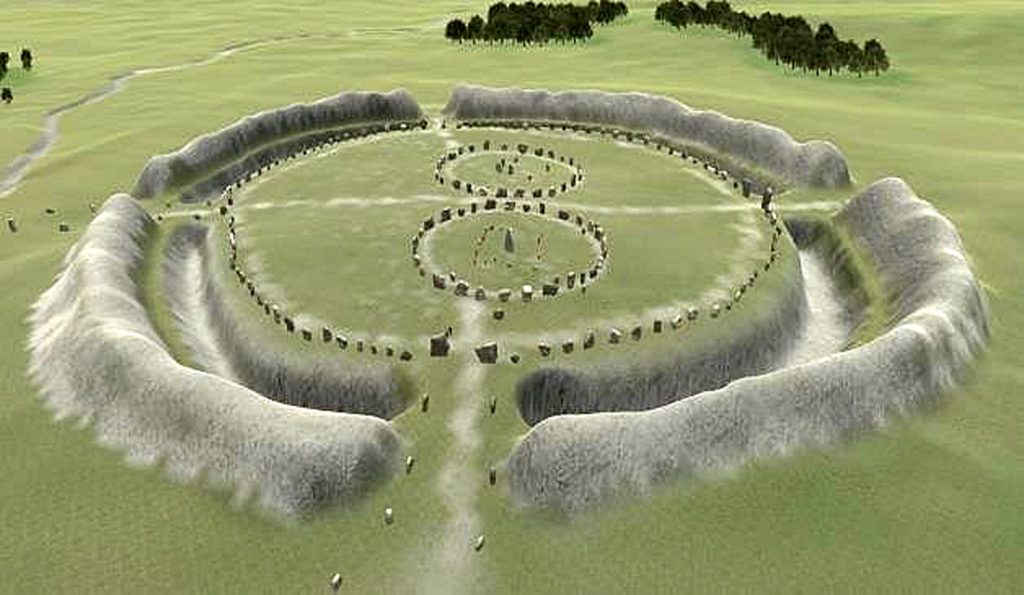

Adding to this picture is the intriguing proposition made in the works of Robert John Langdon, who has argued extensively that stone circles were originally trading hubs. In this interpretation, stone circles were not ritual sites but marketplaces strategically placed along ancient waterways.

If stone circles functioned as trade centres, a credit system would have been necessary to regulate exchanges over time and distance. In a pre-coinage society, a physical tally system would be the most logical tool for tracking trade and credit.

Standing stones surrounding these circles may not have been symbolic or astronomical markers alone, but upright ledgers were used to keep track of who owed what, who traded how much, or who held credit within the community. Each set of notches or strokes on a stone could have represented quantities of goods exchanged, debts owed, or rights to future returns.

Critically, this idea also explains a common counterargument: why don’t we see tally marks on 5,000- to 6,000-year-old stone circles today? The answer may lie in weathering and erosion. Unlike Ogham stones—which are only around 1,500 years old—earlier tally marks carved into upright stones may have been completely worn away over millennia. This supports Langdon’s view that earlier credit-tracking systems would have left only the structural remnants, not visible inscriptions.

Additionally, standalone prehistoric stones—often dismissed as boundary or ritual markers—may have once carried tally marks of their own. These could have served as proto-milestones, indicating distances to the nearest settlement, river access point, or trade centre. The Romans famously used carved milestones for this purpose, and it’s plausible that they borrowed the idea from older, indigenous systems already in place in Britain and Ireland.

The enigmatic symbol stones of the Picts in Scotland further support this. Although still undeciphered, these carved stones often appear as non-phonetic symbols, not a written language in the modern sense. Some researchers have proposed that they may have represented ownership marks, trade identifiers, or tally-like records. The conceptual overlap with Ogham is striking: both use linear carvings on stone in a structured but non-obviously linguistic way, likely reflecting regional traditions of symbolic recording in early societies.

In this context, Ogham inscriptions may represent the final stage of an earlier practice: transforming a basic numerical or symbolic tally system into a formalised script used for legal and social recording. the final stage of an earlier practice is transforming a basic numerical or symbolic tally system into a formalised script for legal and social recording.

So Which Is It: Language or Ledger?

The truth may be that both interpretations are right, just at different phases of development.

As we recognise it today, Ogham may be the formalisation of an older, tally-based visual system. Over time, this practical counting tool could have merged with the growing need to record ownership, identity, and social ties in an increasingly stratified tribal society.

As oral traditions began to falter and literate culture crept in from Roman Britain, tally marks may have been absorbed into a phonetic system shaped by existing tribal practices.

Why This Matters

If true, this rethinking of Ogham would:

- Push its functional origins, perhaps centuries earlier than currently believed.

- Highlight the economic and administrative sophistication of pre-Christian Ireland.

- Challenge the assumption that early scripts always began with language.

- Offer a practical explanation for how trade was regulated in prehistoric stone circles, seen as financial centres rather than ceremonial ones.

It opens the door to re-reading early inscriptions with a new lens—not just as words but as a recording system rooted in trade, movement, and ownership.

From Megaliths to Ogham: The Evolution of Stone Communication

To truly understand the origins of Ogham, we must widen our lens to include the megalithic period, thousands of years before the first recognised Ogham inscriptions. Many standing stones and stone circles erected during that time may not have been purely ceremonial or astronomical — they may have represented the earliest attempts at visual communication. These original stones could have carried tally-like marks, now erased by millennia of weathering, used to track trade, movement, or shared resources between communities.

It’s plausible that some of these early tallies evolved to include rudimentary symbols, perhaps the first representation of names or places, acting as identifiers in a trading or transport network. Much like Roman milestones centuries later, megalithic stones may have marked the distance to key locations, with early carvings denoting either the destination or the owner of credit associated with that point.

Over time, this system would have gradually evolved. As societies became more complex, these proto-marks may have become standardised into recognisable characters, leading to a proto-script — an expandable but straightforward visual language. This natural evolution would explain why some Ogham characters remain indecipherable today: they may originate from symbolic or numeric shorthand and were no longer used when the formalised script emerged.

In this way, Ogham can be seen not as a sudden invention but as the culmination of a much older practice — a lineage of symbolic marking systems rooted in prehistoric credit, trade, distance-tracking, and ownership records. By reframing these early stones as proto-documents, we can better appreciate how literacy emerged organically from practical needs long before it was formalised in stone.

Expanding the Tally Theory Further

One compelling angle to consider is how the shift from oral to visual record-keeping might have required transitional symbolic systems — forms of notation that were neither fully linguistic nor purely numerical. Ogham may represent a transitional form, bridging the gap between primitive counting and emerging literacy. In this light, the earliest users of Ogham weren’t writing names so much as marking values, entitlements, or exchanges, with phonetic clarity emerging later as a natural evolution.

Furthermore, the placement of Ogham stones at key crossroads, near river crossings, or adjacent to prehistoric pathways supports the idea of their role in territorial and economic control. These were not random grave markers — they were visible, public markers possibly denoting access rights, trading permissions, or debt settlements within tribal networks. Their visibility was part of their function.

It’s also worth noting that not all Ogham inscriptions conform neatly to the commemorative formula. Some are fragmentary, cryptic, or contain repeated characters that defy straightforward translation. This suggests that some stones may not be linguistic at all but remnants of earlier or alternative systems — perhaps counting symbolic referencing, or even tally-based rituals linked to cyclical trade or seasonal gatherings.

Finally, Ogham’s survival into early Christian Ireland — where it was used to carve Latin-scripted messages and adapted for secret codes in monastic settings — shows its flexibility and symbolic prestige. This reinforces the idea that it wasn’t just a practical tool but one imbued with cultural continuity, tracing its roots back to practical functions now obscured by erosion and academic convention.

Conclusion

The Ogham script is undoubtedly a linguistic treasure. But before it was used to honour ancestors or declare territory, it may have started as something humbler but equally powerful: a tool for keeping count.

In a world where archaeology is finally embracing landscape patterns, trade infrastructure, and pre-literate intelligence, we re-evaluate what those ancient notches may have meant.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?