Archaeology: A Bad Science?

Archaeology, often hailed as the key to understanding our past, stands at a contentious crossroads between the humanities and the sciences. Archaeology is largely interpretative and subjective, unlike pure sciences, which rely heavily on quantitative data and mathematical models to test hypotheses. The field depends on analysing artefacts, structures, and cultural remains, often incomplete or degraded. This reliance on fragmentary evidence means that much archaeological interpretation is speculative, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. The subjective nature of archaeology raises questions about its scientific rigour, as interpretations can vary significantly depending on the archaeologist’s perspective, cultural background, or theoretical framework.

In contrast, pure sciences like physics, chemistry, and biology adhere to strict methodologies that prioritise empirical data and mathematical precision. These disciplines employ controlled experiments, reproducible results, and quantitative analysis to validate theories and build on existing knowledge. Hypotheses in pure sciences are rigorously tested, often through repeated experiments, to prove or disprove them. The mathematical models in these fields are designed to predict outcomes with high accuracy, leaving little room for personal bias or interpretive flexibility. This reliance on complex data and reproducibility sets pure sciences apart from more interpretative disciplines like archaeology, where conclusions are often inferred from indirect evidence and subject to ongoing debate.

While archaeology provides invaluable insights into human history and culture, its status as a “science” is frequently challenged due to its inherent subjectivity. The field’s heavy dependence on interpretation rather than objective data can lead to multiple, often conflicting, narratives about the past. Archaeology usually deals with probabilities and possibilities rather than certainties, unlike pure sciences, where theories can be definitively proven or disproven. This makes archaeology a unique and valuable discipline. Still, one that straddles the line between science and the humanities, leading some to argue that it is more of a social science than an actual, data-driven science. As a result, the conclusions drawn in archaeology should be viewed critically, understanding that they are often shaped as much by the archaeologist’s perspective as by the evidence itself.

In the competitive world of academia, the struggle for funding is fierce, particularly in fields like archaeology, where financial resources are often scarce. Universities and research institutions face significant pressure to secure grants and sponsorships, which are essential for conducting fieldwork, preserving artefacts, and supporting academic staff. Given the limited budget allocated to archaeology, institutions are often forced to prioritise projects that promise high visibility and public interest, sometimes at the expense of rigorous scientific inquiry. This competition can lead to a climate where sensationalism takes precedence over careful, evidence-based research, with archaeologists making bold claims to capture the media’s and potential funders’ attention.

The egos of leading professors and researchers further complicate this landscape. In their quest for prestige and recognition, some academics may undermine their peers to secure funding and enhance their credibility. This can create a toxic environment where collaboration and peer review are replaced by rivalry and one-upmanship. The need to stand out and secure funding can lead to premature announcements of discoveries or theories that have yet to be fully vetted or substantiated. These announcements often make headlines and capture the public imagination. Still, they also contribute to a growing perception that archaeology is a field rife with contentious guesses rather than solid, verifiable knowledge.

As a result, the discipline of archaeology risks becoming a series of unproven hypotheses, each vying for attention but needing more robust evidence to withstand critical scrutiny. This trend diminishes the field’s credibility as the public becomes increasingly sceptical of claims that are later debunked or revised. The focus on media appeal and public interest, driven by the need for funding, can overshadow the meticulous and often slow scientific validation process essential to any credible discipline. In the long run, this erodes trust in archaeology and undermines its potential to contribute meaningful insights into our understanding of the past.

The misinterpretations surrounding Stonehenge, Iron Age hill forts, and linear earthworks like dykes stem from a failure to fully integrate emerging technologies and scientific methods into archaeological research. For instance, Stonehenge is often dated to the Neolithic period, around 3000 to 2000 BCE. However, as discussed in the blog “The Stonehenge Code”, significant evidence, including Mesolithic carbon dates from quarry sites associated with Stonehenge, was largely ignored. The Mesolithic carbon dates suggest activity at these quarries—and potentially the beginnings of Stonehenge itself—could have occurred much earlier, possibly as far back as 8500 BCE.

This oversight exemplifies how the subjective nature of archaeology can lead to selective interpretation of data. Suppose a more scientific approach incorporating probability and statistical analysis had been employed. In that case, it might have revealed that the likelihood of these earlier dates being relevant to Stonehenge’s construction was much higher. Instead of discarding the Mesolithic evidence, a rigorous application of mathematical models could have provided a more nuanced understanding of the site’s history, possibly redefining the origins of one of Britain’s most iconic monuments. This tendency to favour prevailing theories over emerging evidence highlights the risk of allowing unproven hypotheses to dominate the discourse.

Similarly, classifying over 3,300 sites across Britain as “Iron Age hill forts” reveals another instance of entrenched archaeological assumptions. As discussed in the blog on Iron Age hill forts, many of these earthworks have no concrete evidence that they were constructed during the Iron Age or served as fortifications. The absence of mass graves or signs of warfare at these sites challenges the accuracy of their classification as “forts.” This misclassification has stifled further research, as archaeologists may need to pay more attention to evidence suggesting alternative uses or periods.

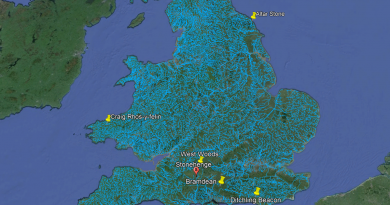

The issue extends to linear earthworks or dykes, traditionally attributed to the Saxon period due to their names. However, LiDAR technology has revealed these structures to be much older and likely filled with water, suggesting they served as transport hubs rather than defensive boundaries. Discoveries such as the Roman barge at Car Dyke indicate that these features predate the Saxon era, further supported by recent scientific analyses pointing to a Mesolithic origin. This evidence fundamentally changes our understanding of these dykes, emphasising the need to integrate new findings into the archaeological narrative.

The failures to interpret these sites accurately often stem from a broader oversight in archaeological analysis: the post-glacial flooding that reshaped Britain’s landscape. According to research on post-glacial flooding, large portions of Britain were submerged underwater for thousands of years after the last Ice Age. This created waterways essential for transportation, trade, and monumental construction, allowing a megalithic civilisation to thrive. Many archaeologists, lacking training in hydrology, have not fully grasped the significance of this waterlogged environment, leading to misinterpretations about the origins and functions of these prehistoric sites.

This dysfunction has contributed to a discipline of arguably 70% suggestive fiction and only 30% scientific fact, where speculative interpretations often overshadow hard evidence. By failing to consider the dynamic nature of ancient landscapes and the significance of waterways, archaeology risks misrepresenting the true complexity of Britain’s prehistoric past. A more interdisciplinary approach, incorporating hydrology, geology, and climate science, is crucial to reconstructing these environments accurately and moving beyond preconceived notions.

In conclusion, while archaeology employs various scientific techniques, it is not immune to human biases and the influence of external pressures. The reliance on subjective interpretation over empirical data, the competition for funding, and a tendency to favour popular narratives have contributed to a discipline that often straddles the line between science and speculative storytelling. By embracing a more evidence-based, interdisciplinary approach, archaeology can enhance its credibility and offer a more accurate exploration of our past, reducing the current imbalance between fiction and fact in the field.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, which has the most extensive collection of archaeology blogs and investigations, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain