The Great Antler Pick Hoax

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.0.1 The Archaeological Evidence Presented Currently

- 1.0.2 The Problems with This Hypothesis

- 1.0.3 Lack of Evidence in Large Ditches

- 1.0.4 The Lack of Antler Pick Marks in Ditches

- 1.0.5 The Role of Other Tools in Prehistoric Excavation

- 1.0.6 Comparison of Stone Axes and Antler Picks for Cutting Chalk Bedrock

- 1.0.7 Reassessing Radiocarbon Dates and Antler Pick Contexts

- 1.0.8 New Hypotheses and Directions

- 1.0.9 The Neolithic Power Axe: Strength & Speed Gains vs the Antler-Pick Story

- 2 Conclusion

- 3 Glossary of Key Terms

- 4 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 5 Further Reading

- 6 Other Blogs

Introduction

Antler picks, primarily derived from red deer, are frequently cited in archaeological narratives as essential tools used by prehistoric societies for monumental construction and large-scale ditch digging. These tools, often uncovered in association with ancient sites, have been instrumental in dating some of Britain’s most iconic Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments. Despite their prominence in archaeological interpretation, the reliance on antler picks to date sites raises significant methodological and evidentiary concerns. This blog explores the challenges surrounding using antler picks as dating tools, questioning the robustness of current hypotheses. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

The Archaeological Evidence Presented Currently

The discovery of antler picks at sites such as Stonehenge, Cissbury Ring, and other prehistoric monuments has long been interpreted as evidence of their use in earth-moving activities. Often found in ditch fills or nearby deposits, these tools have been subjected to radiocarbon dating, providing approximate ages for the associated construction phases.

For example, antler picks are frequently cited as evidence of early activity at Cissbury Ring, a large Iron Age hillfort in Sussex. Radiocarbon dating of these tools has been instrumental in suggesting Neolithic origins for certain phases of the site’s development (Prehistoric Britain). Similarly, the association of antler picks with the construction of henges and other significant monuments has shaped narratives about labour organisation and the technological capabilities of prehistoric communities. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

The Problems with This Hypothesis

While the presence of antler picks at archaeological sites is indisputable, their use as definitive evidence for dating or construction activities is fraught with challenges:

- Bronze Age Dates for Antler Picks vs. Mesolithic Site Radiocarbon Dates: Many antler picks found at these sites have Bronze Age radiocarbon dates, yet the broader site contexts often yield earlier Mesolithic dates. This disparity suggests that antler picks may have been deposited much later than the initial construction of these monuments. The mismatch in dates raises questions about their relevance to the primary phases of monument construction.

- Antler Picks in Abandoned Mines: Evidence from flint mines, such as Cissbury Ring, suggests that antler picks may have been used in later, opportunistic foraging rather than during the primary phases of mining. This pattern aligns with examples from South Africa, where scavengers using inefficient tools later reopened abandoned gold mines. These scavengers left isolated tool marks and scattered debris, much like the occasional antler pick marks in chalk mines.

- Localised and Isolated Marks: If antler picks were the primary tools for excavation, one would expect to find consistent and widespread marks in ditches and mining walls. Instead, the marks attributed to antler picks are often localised and inconsistent, suggesting they were the efforts of scavengers rather than evidence of systematic use in construction.

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Lack of Evidence in Large Ditches

Large ditches, such as those found at henges and causewayed enclosures, are often attributed to the labour-intensive use of antler picks. However, there is a conspicuous absence of direct evidence supporting this hypothesis. Excavations of these features frequently reveal profiles with sharp, clean edges inconsistent with the marks expected from antler tools.

The scale of these ditches also presents a logistical challenge. For instance, the ditches at Avebury and Durrington Walls span several metres in width and depth. The volume of earth removed from such features would have required a level of labour coordination and tool efficiency that antler picks alone seem ill-suited to provide. Moreover, at Avebury, human bones outnumber antler picks in the excavation layers, raising further doubts about the reliance on these tools for large-scale construction. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

The Lack of Antler Pick Marks in Ditches

One of the most striking issues is the lack of discernible antler pick marks in the profiles of excavated ditches. If antler picks were the primary digging tools, one would expect to find characteristic striations or impressions consistent with their use. However, such marks are rarely, if ever, observed. Instead, isolated antler pick marks, often attributed to later scavenging activity, align with opportunistic rather than systematic tool use.

This discrepancy has led some researchers to speculate that other tools or methods—such as wooden spades, teamwork, or even fire to soften the ground—may have been employed. The reliance on antler picks as the sole or primary digging tools may represent an oversimplification of prehistoric technological practices. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

The Role of Other Tools in Prehistoric Excavation

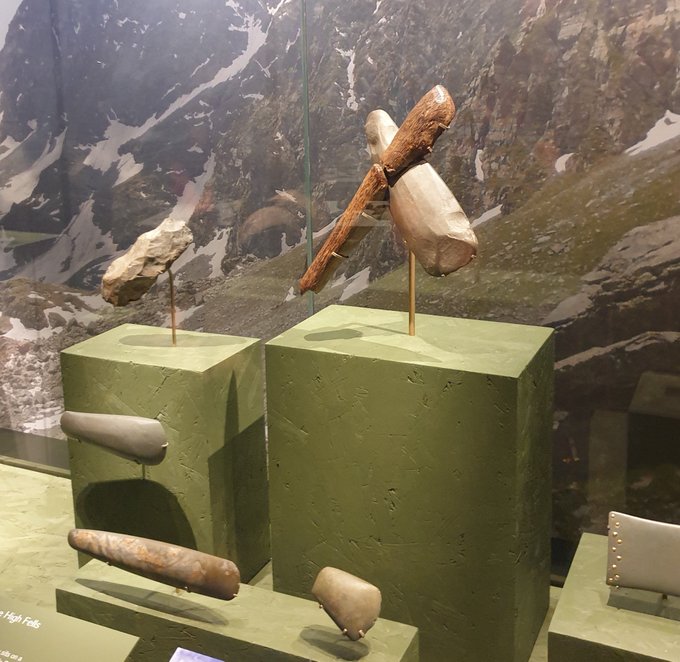

In addition to antler picks, tools such as stone axes, wooden spades, and even simple digging sticks were likely part of the prehistoric toolkit. Stone axes, for instance, are robust and capable of cutting through roots or chopping through more complex soils. Their durability and cutting power would make them a more practical choice for tasks requiring significant force or precision.

Although less durable, wooden spades could be used effectively in softer soils and may have been easier to manufacture in large quantities. Combined with teamwork and systematic labour organisation, these tools could have complemented antler picks in large-scale excavation projects. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

When comparing these tools, antler picks would not have been the most suitable choice for digging ditches as deep as 35 feet, such as those at Avebury. Stone axes offer superior strength and are less likely to break under pressure, while wooden spades provide a more ergonomic option for moving large amounts of soil. Antler picks, by contrast, are prone to wear and breakage, making them less efficient for sustained heavy labour. Their primary advantage lies in their availability and ease of manufacture rather than their effectiveness as digging tools. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Comparison of Stone Axes and Antler Picks for Cutting Chalk Bedrock

| Feature | Stone Axes | Antler Picks |

|---|---|---|

| Durability | High—capable of withstanding repeated impacts | Moderate—prone to wear and breakage |

| Effectiveness | Effective at cutting through chalk and harder soils | Limited effectiveness against hard chalk |

| Ease of Manufacture | Requires skill and time to produce | Easier to craft with available materials |

| Ergonomics | Heavier but provides better leverage for cutting | Lightweight but less effective for sustained effort |

| Suitability for Depth | Suitable for deeper excavation tasks | Unsuitable for large-scale, deep ditches |

| Overall Efficiency | Superior for cutting and excavation in hard materials | Inferior, best used as supplementary tools |

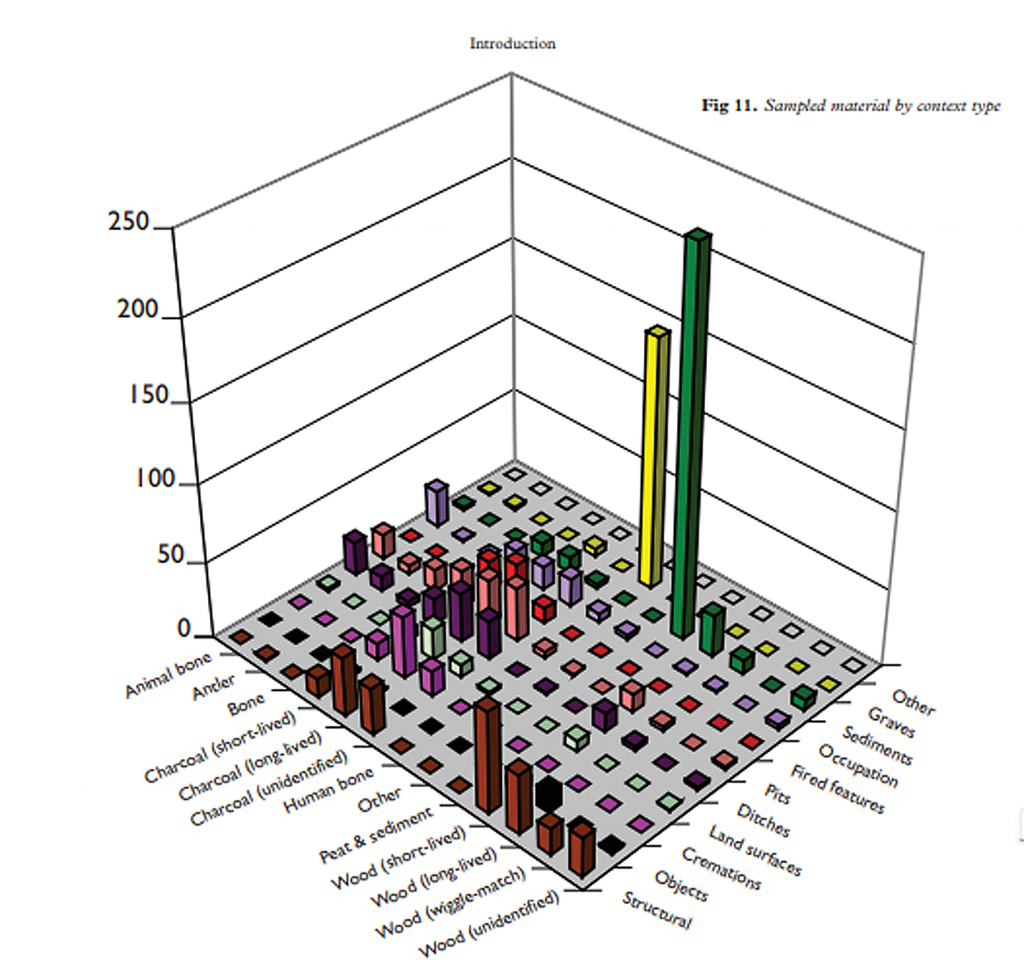

Reassessing Radiocarbon Dates and Antler Pick Contexts

One of the most critical oversights in the current antler pick hypothesis is the radiocarbon dating of associated artefacts. While antler picks generally yield Bronze Age dates, the broader radiocarbon contexts of some sites, such as Avebury, suggest earlier Mesolithic activity. This disparity highlights the complexity of site stratigraphy and challenges the assumption that antler picks were contemporaneous with significant construction phases. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Furthermore, the frequency of human bones in the excavation layers at Avebury surpasses that of antler picks, suggesting a ritualistic or commemorative aspect to these sites that is often overlooked. This pattern further diminishes the likelihood of antler picks as primary construction tools, reinforcing their probable role as opportunistic or supplementary implements.

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

New Hypotheses and Directions

Given the limitations of the antler pick theory, alternative hypotheses must be developed to explain the construction of monumental ditches:

- Integrated Tool Use: A combination of wooden spades, stone tools, and fire-setting techniques could explain the efficiency and scale of prehistoric earthworks. This approach accounts for the lack of visible antler pick marks and the challenges of chalk bedrock.

- Specialised Labour: Prehistoric societies may have organised labour into specialised teams, each equipped with tools suited to specific tasks, enhancing overall efficiency.

- Ritual Contexts: Antler picks may reflect ritualistic deposition unrelated to practical construction, aligning with the broader symbolic landscape of prehistoric sites.

- Temporal Layers of Activity: Recognising the complex, multi-phase use of sites can help untangle the chronological overlap between Mesolithic artefacts and later Neolithic or Bronze Age construction efforts.

By embracing multidisciplinary perspectives and exploring alternative hypotheses, researchers can construct a more accurate and nuanced understanding of Britain’s prehistoric past. This shift challenges outdated assumptions and opens new avenues for investigating the ingenuity and adaptability of ancient societies in creating their monumental landscapes.

The Neolithic Power Axe: Strength & Speed Gains vs the Antler-Pick Story

What makes this tool different from a modern axe?

- Heavier head (stone, often ~2× a steel head).

- Heavier handle (green/undried wood, not kiln-dried), so the whole tool weighs more.

- Short, thick grip built for big hands and close control—more like a sledge than a DIY hatchet.

What that means in the hand (no jargon):

This setup puts much more load on the wrist and forearm. To swing at the same cadence with the same control as a modern 3.5-lb felling axe, a Neolithic user needed roughly 30–50% more wrist/forearm strength. That fits the Langdon‘s Megalithic Builder profile in my books (c. 6′6″, Cro-magnon, large hands/feet): these tools match bigger, stronger users.

Why head-only comparisons are misleading:

Axe performance is a system (head + haft + balance). Modern catalogue rules (“head lbs × 10 ≈ handle inches”) were tuned to lightweight steel heads and kiln-dried ash/hickory. They simply don’t apply to heavy stone heads on green-wood hafts with short, thick levers. The Neolithic design trades long, whippy swings for short-arc, high-impulse blows—superb control, higher local torque.

So what does this do on a real monument? (Avebury as the test)

- Avebury’s ditch ≈ 96,000 m³ of chalk.

- The antler-pick tale asks for ~1.5 million work-hours (≈ 15–16 h/m³).

- Put real tools in the hands of robust users—hafted stone axes + wooden spades—and add the wet-ditch reality (high water table, flat-bottom profile → dredging rather than dry “mining”):

- Conservative (no water help): ~5 h/m³ → about 3× faster than antlers.

- With water assist (moat/dredge): ~2 h/m³ → up to 8× faster than antlers.

Bottom line for this section:

Neolithic builders were not poking chalk with antlers for years on end. They used heavy, close-balanced power axes that suit larger, stronger people—and, in a wet landscape, those tools collapse build times by a factor of 3–8. That’s why large earthworks and stone projects are logistically credible in the timeline we’ve set out.

Conclusion

The so-called “antler pick” narrative wilts under basic logistics, hydrology, and the toolset we actually see. There are nowhere near the numbers of antlers you’d need for industrial-scale ditching; most that are found aren’t pruned for heavy chalk work; and the ditch forms themselves (flat bottoms, standing water) say moat/dredge, not quarry face.

Set the story back on its feet:

- The landscape is wet in the phases that matter. Water does half the labour if you understand it.

- The tools are heavy, close-balanced axes with green-wood hafts and big grips—perfect for larger, stronger builders (the Langdon profile).

- The productivity uplift is real: with proper tools and wet-ditch practice you move from ~15–16 h/m³ (antlers) to ~2–5 h/m³, i.e., 3–8× faster—turning “heroic myth” into practical engineering.

- The timeline holds: these methods make Avebury- and Stonehenge-scale works achievable without fantasy headcounts or modern machinery.

The “Great Antler Pick Hoax” isn’t just about a bad tool; it’s about a bad model. Replace it with water-first engineering and Neolithic power tools built for big hands—and the megalithic world suddenly looks exactly as capable as the monuments they left behind.

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Glossary of Key Terms

- Antler Pick: A tool made from the shed antler of a red deer, traditionally believed to be used for digging and excavating in prehistoric times.

- Bluestones: The smaller stones used in the construction of Stonehenge, originally from the Preseli Mountains in Wales.

- Bronze Age: A period in human history, following the Stone Age, characterized by the use of bronze tools and weapons (traditionally dated in Britain as 2500-70 BCE).

- Bur: The thickest part of the antler attached to the deer’s head.

- Dyke: An artificial waterway, often with raised embankments and drainage systems, used to control water. This term has been reinterpreted by the authors as being a channel for transport.

- Flint: A hard, grey rock used to make tools, weapons, and to start fires during the Neolithic period.

- Flint Knapping: The process of shaping flint by striking flakes off the stone to make tools

- Henge: A type of Neolithic monument, typically consisting of a circular bank and ditch, with an entrance.

- Holocene: The current geological epoch, beginning about 11,700 years ago, following the end of the last Ice Age.

- Iron Age: A period in human history following the Bronze age marked by the increased use of iron tools and weapons. In Britain it traditionally dates from 700 BCE to 43 CE.

- LiDAR: (Light Detection and Ranging) Remote sensing technology that uses laser pulses to measure the distance to the earth’s surface, creating detailed maps.

- Lynchets: Terraced formations on hillsides, traditionally associated with agriculture but reinterpreted as possible dykes used for water control.

- Mesolithic Period: The Middle Stone Age, characterized by hunting and gathering societies.

- Megalithic: Large stone structures, usually built during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

- Neolithic Period: The New Stone Age, characterized by the development of agriculture and settled societies.

- Paleochannel: A remnant of an ancient river or stream channel, often buried beneath sediment.

- Post-Glacial Flooding: The concept of increased water levels that occurred after the last Ice Age, which had a significant effect on prehistoric landscapes and settlements.

- Ramparts: Defensive walls, often made of earth, built around fortifications like hill forts.

- Radiocarbon Dating: A method of dating organic materials by measuring the amount of the radioactive isotope carbon-14 present in the sample.

- Tine: The pointed projections on a deer antler, specifically the brow, bez and trez.

- Trez: The third tine on a deer antler.

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives. (The Great Antler Pick Hoax).

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

(The Great Antler Pick Hoax).