Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Book – eFlipbook

- 3 Briefing Document

- 4 Prehistoric Britain: A Study Guide

- 5 FAQ: Prehistoric Britain and Hydrology

- 5.1 1. How did dykes function as waterways in prehistoric Britain, considering they appear dry today?

- 5.2 2. What evidence suggests that dykes were used as canals?

- 5.3 3. How did prehistoric people regulate water flow in dykes to overcome changes in elevation?

- 5.4 4. How did the post-glacial period impact river systems and landscapes in Britain?

- 5.5 5. What is the significance of peat in understanding prehistoric hydrology?

- 5.6 6. What evidence suggests that structures like Stonehenge were once surrounded by water?

- 5.7 7. How did prehistoric communities potentially use these flooded landscapes?

- 5.8 8. What are some modern techniques used to investigate prehistoric hydrology?

- 6 Further Reading

- 7 More Blogs

Introduction

My recent exploration into Britain’s prehistoric landscape has opened my eyes to a fascinating and often overlooked aspect of our history: the impact of post-glacial flooding. The sheer magnitude of meltwater released at the end of the last ice age dramatically reshaped the environment, creating vast waterways that are notably more significant than the rivers we see now. This realisation has sparked my curiosity to understand how these ancient waterways influenced the lives of our ancestors and shaped the landscape we know today.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

Summary

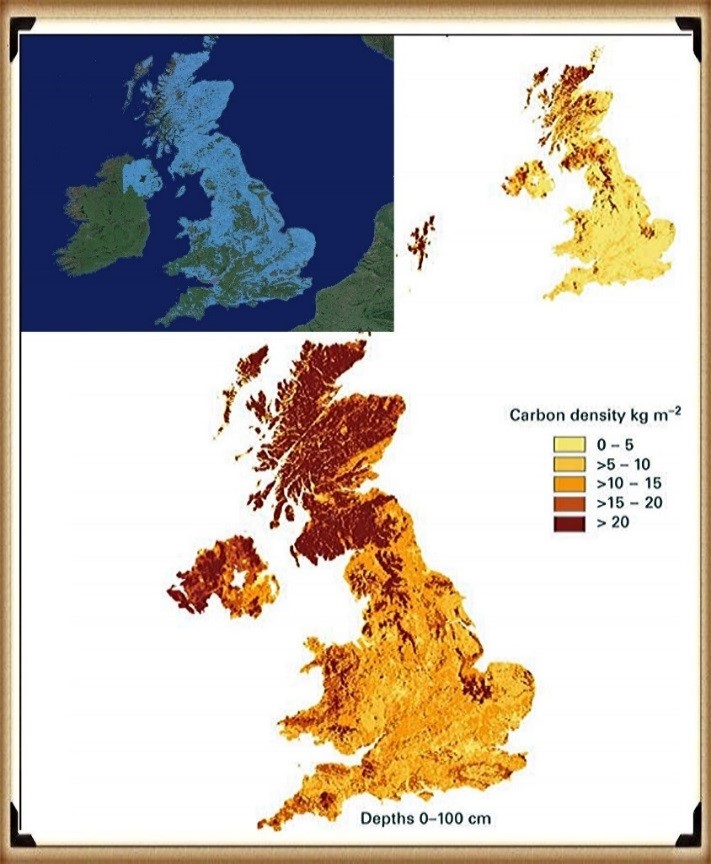

The evidence for these massive, prehistoric rivers lies scattered across the British Isles, often hidden beneath soil layers and obscured by time. But with careful observation and a willingness to challenge conventional thinking, the signs become apparent. Geological maps reveal the presence of extensive superficial deposits, hinting at the scale of these ancient waterways. Peat bogs, formed in the wake of retreating glaciers, offer further clues, with their deep layers interspersed with silt and sand deposits, a testament to the cyclical nature of flooding events.

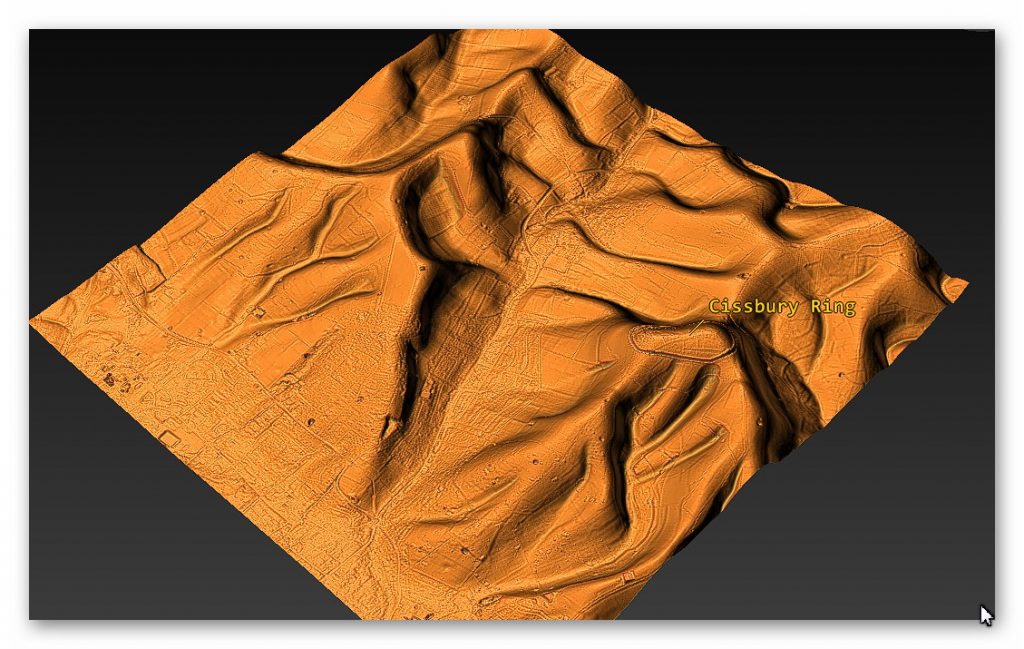

One of the most striking pieces of evidence is the presence of ancient settlements along the shorelines of these long-gone rivers. Iron Age hillforts, often perched atop strategic vantage points, offer a glimpse into the past, suggesting that our ancestors recognised the advantages of settling near these waterways. Once considered solely defensive structures, these hillforts take on a new meaning when viewed through a flooded landscape. Could they have also served as vital hubs for trade and transportation, connected by a network of navigable rivers?

The sources I’ve consulted within my books point to the limitations of traditional archaeological interpretations, which often fail to account for the significant impact of post-glacial flooding. The focus on terrestrial landscapes has usually led to underestimating these ancient waterways’ role in shaping early human settlements and cultural practices. Reexamining existing archaeological data, combined with new insights from techniques like LiDAR mapping, could unlock a wealth of information about our ancestors’ relationship with these flooded landscapes.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

Consider, for instance, the dykes of Britain, enigmatic earthworks that crisscross the landscape. While their purpose has been debated for centuries, my books suggest a compelling connection to the prehistoric river systems. The dykes, they argue, were not simply defensive barriers but intricate components of a sophisticated water management system designed to channel and control the flow of these immense waterways. The fact that every investigated Dyke shows a connection to these ancient rivers is a striking piece of evidence that supports this theory.

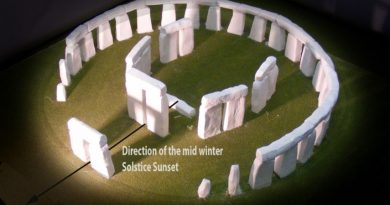

The implications of this hypothesis are profound. If these dykes were indeed part of a vast water management network, it suggests a level of engineering sophistication and social organisation that challenges our current understanding of prehistoric Britain. The books point to specific examples, like the dykes at Winterbourne Crossroads, which not only reveal the presence of water at Stonehenge in both the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods but also provide insights into the burial practices of that time. The alignment of these dykes with the ancient river levels paints a vivid picture of a society deeply connected to and reliant upon the waterways that shaped their world.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

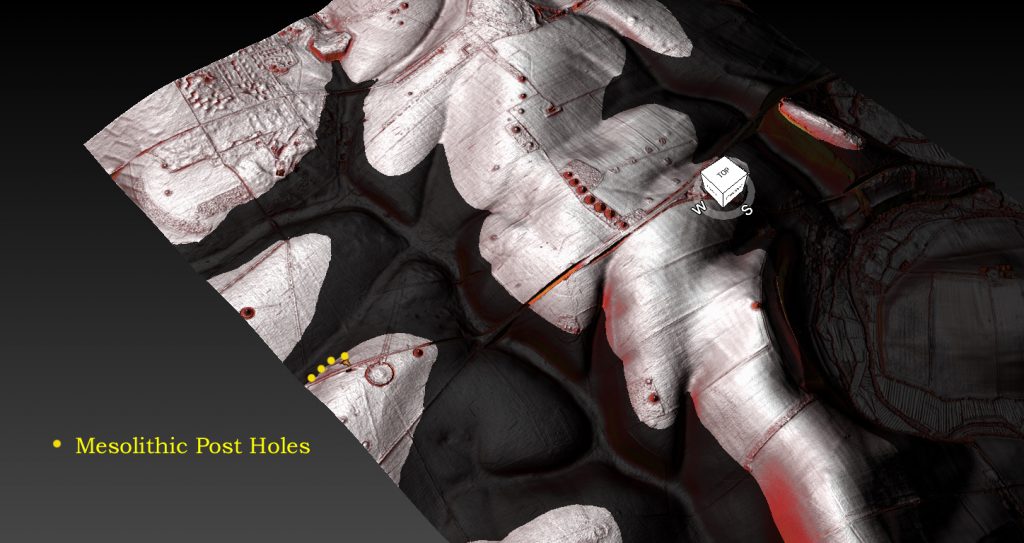

The information also draws attention to post holes and mooring points at sites like Stonehenge and Durrington Walls, further solidifying the case for a significant water presence during the Neolithic period. These seemingly mundane features, often overlooked in traditional archaeological interpretations, offer a tangible link to when these sites were situated along the shorelines of prehistoric rivers. The post holes at Stonehenge Bottom, for example, not only provide evidence of a river’s existence but also suggest its use in transporting the bluestones from the Craig Rhos-Y-Felin quarry.

The books advocate for a shift in our perspective, urging us to view these prehistoric monuments not as isolated structures on a dry landscape but as integral parts of a vibrant, interconnected water world. This paradigm shift could revolutionise our understanding of ancient Britain, revealing the ingenuity and adaptability of our ancestors who navigated and thrived in this dynamic environment.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

The evidence includes numerous examples of how the post-glacial flood hypothesis can shed new light on seemingly inexplicable features of the landscape. Woodhenge, for instance, takes on a new role as a potential fire beacon or lighthouse, guiding boats along the much larger River Avon. Old Sarum’s intricate system of ditches and dykes, once interpreted solely through a defensive lens, is reimagined as a complex system of moats, highlighting the presence of a higher water table during the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.

The remarkable discovery of Silbury Avenue, based solely on a few crop marks and the application of the post-glacial flood hypothesis, further emphasises the power of this new way of thinking. This finding confirms the theory of higher river levels in the past and underscores the potential for using this approach to uncover and date hidden monuments across Britain.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

Another intriguing piece of evidence is the positioning of Long Barrows, often situated on hillsides overlooking ancient waterways. These barrows, far from being random burial sites, served as navigational aids for those travelling along the vast river systems of Mesolithic Britain. Their strategic placement, offering clear lines of sight along the river routes, hints at a society that relied heavily on water transport and understood the importance of visual landmarks in navigating this complex landscape.

Conclusion

This journey into Britain’s flooded past has left me with a profound sense of wonder and a renewed appreciation for the intricate connections between landscape, environment, and human history. The evidence, though often subtle, is undeniable. By embracing the post-glacial flood hypothesis, we can better understand our ancestors’ lives, ingenuity, and deep connection to the waterways that shaped their world.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

The Book – eFlipbook

– Also available as a paperback on Amazon https://www.amazon.co.uk/Prehistoric-Rivers-Robert-John-Langdon/dp/B09L3VXH5F

Briefing Document

Main Theme: The excerpts from “Mini Series Prehistoric Rivers.pdf” and “Post-Glacial Flooded Britain v2.1.pdf”, along with promotional material for LiDAR maps, highlight the significant impact of post-glacial flooding on the British landscape, particularly during the early Holocene period. The authors argue that conventional understanding of river formation and sediment deposition underestimates the scale and intensity of these floods.

Key Ideas and Facts:

- Massive Meltwater Release: Mathematical models presented in the source suggest a minimum release of 8.42 quadrillion tonnes of water on the UK at the end of the last ice age, equivalent to “98425.2 inches of rain falling on every square inch of Britain’s landmass.” This volume significantly impacted river discharge rates, groundwater levels, and overall landscape formation.

- Increased River Discharge: Analysis of the Thames River system, using BGS superficial maps and borehole data, reveals a peak discharge rate of 2450 m3/s during the Holocene, representing a 3723% increase compared to current averages. This finding challenges traditional views of the Thames’ formation and highlights the need to reassess the impact of past floods on other British rivers.

- Peat as Evidence: Peat formation, beginning around 10,000 years ago, provides crucial evidence of post-glacial flooding. The presence of deep peat layers interspersed with silt and sand deposits indicates prolonged periods of wetland conditions punctuated by intense flooding events. Case studies from the Upper Dee and Somerset Plain exemplify this pattern.

- Widespread Flooding: The sources present evidence of significant flooding events across various locations in Britain, including the Thames Valley, the Somerset Levels, and Welsh river catchments. These findings suggest a widespread phenomenon that reshaped the British landscape during the early Holocene.

- Limitations of Traditional Dating Methods: The authors challenge the accuracy of traditional dating methods for river terraces and sediment layers. They argue that questionable dates and inconsistencies in sediment accumulation rates necessitate a re-evaluation of established timelines.

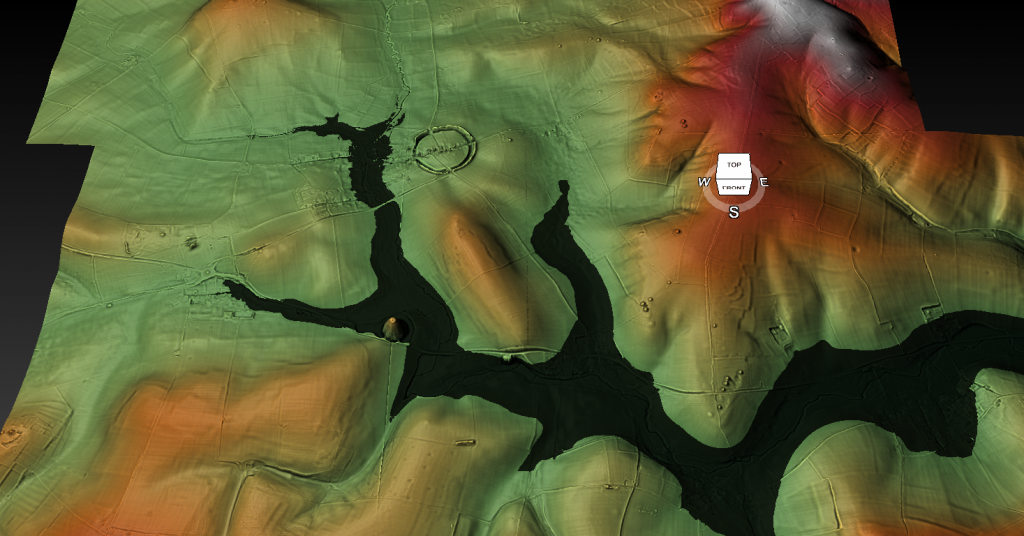

- LiDAR Technology as a Tool: The promotional material for LiDAR maps suggests the technology’s potential to reveal hidden features of the landscape, potentially uncovering further evidence of past flooding events and providing more accurate data for future research.

Supporting Quotes:

- “These models showed us that a minimum of 8.42 quadrillion tonnes of water was released on the UK at the end of the last ice age.”

- “The conclusion of this study was that the current average discharge of 65.8 m³/s was increased by 3723% within the watershed area”

- “This increases the Thames Flood Model from a discharged 2,450 m3/s to 12,250 m3/s, which reflects more accurately the North American Discharge Model.”

- “Peat (turf) is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation… Peat forms in wetland conditions, where flooding obstructs flows of oxygen from the atmosphere”

Further Research:

- Utilize LiDAR data to investigate the topography of river valleys and identify evidence of past floodplains and paleochannels.

- Conduct further analysis of peat deposits across Britain to establish a more comprehensive timeline of Holocene flooding events and their intensity.

- Reassess traditional dating methods for river terraces and sediment layers, incorporating new insights from recent studies and advanced technologies.

- Investigate the impact of post-glacial flooding on early human settlements and their relationship with the changing landscape.

Conclusion:

The evidence presented in the sources suggests that post-glacial flooding played a far greater role in shaping the British landscape than previously acknowledged. These findings have significant implications for our understanding of river formation, sediment deposition, and the history of human presence in Britain. Further research using advanced technologies like LiDAR and improved dating methods will be crucial to refining our knowledge of this pivotal period in British prehistory.

Table of Contents of Source Material

Source 1: “Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101 – Prehistoric Britain” (Blog Post)

- Introduction: The Misconception of Dykes: This section challenges the common perception of dykes as rivers or canals and introduces the concept of groundwater as the source of water in these structures.

- Groundwater Hydrology: This section explains the basic principles of groundwater hydrology, emphasizing how water pressure allows springs and wells to function even on hills.

- Environmental Change and Dyke Adaptation: This section highlights the significant environmental changes that occurred from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age, impacting dyke construction and use.

- Offa’s Dyke: A Case Study in Adaptation: This section examines Offa’s Dyke, suggesting its potential adaptation for navigation across dry river valleys using a prehistoric lock system.

- Dykes as Ancient Roads: This section explores evidence suggesting that dykes, including Offa’s Dyke, may have been repurposed as roads in later periods.

- Prehistoric Lock Systems: This section proposes alternative theories about how prehistoric populations regulated water flow in dykes to facilitate navigation across hills, comparing them to modern lock systems.

- The Role of Springs in Dyke Functionality: This section investigates the connection between springs and dykes, suggesting that dykes were strategically built near springs to replenish water lost due to gradients.

- The Age of Water and Dyke Construction: This section explores the age of groundwater and its implications for understanding the timing and purpose of dyke construction, highlighting the prevalence of linear earthworks in the Northern Hemisphere.

Source 2: “Enigma – Third edition v3.3 (flipbook).pdf” (Book)

- Sea Level Change and River Dynamics: This section investigates the impact of historical sea level changes on rivers, particularly focusing on the discharge rates of the Thames River.

- River Terraces as Evidence of Fluvial Processes: This section examines the formation and significance of river terraces in understanding the long-term evolution of river systems.

- Dew Ponds: Analogies to Prehistoric Moats: This section explores the construction and water sources of dew ponds, drawing parallels to the potential existence of moats around prehistoric sites like Stonehenge.

- Post Holes and Their Significance: This section examines the evidence of post holes at Stonehenge and other sites, suggesting their use in supporting structures, potentially including wooden towers and palisades.

- Doggerland and Its Potential Significance: This section delves into the submerged landmass of Doggerland and its possible connection to the alignment of the Slaughter Stone at Stonehenge.

- Snail Evidence and Environmental Reconstruction: This section analyzes the presence of snail species in archaeological layers to understand past environmental conditions and human activities, particularly concerning the existence of moats.

- The Moats of Old Sarum: This section examines the evidence for moats at Old Sarum, proposing that these ditches were constructed to maintain water levels around the site as the groundwater table dropped.

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks: Origins and Purpose: This section discusses the etymology and historical context of dykes, emphasizing their use in water management and navigation across various cultures and time periods.

- Wansdyke: Evidence for Prehistoric Canal System: This section focuses on Wansdyke, analyzing evidence suggesting its use as a canal system predating Roman occupation and highlighting its repurposing by Roman settlements.

Source 3: “Mini Series A5 format – Prehistoric Rivers.pdf” (Booklet)

- The Last Ice Age: This section provides an overview of the last ice age, including its size and impact on global water distribution.

- Hydrology: This section delves into the basics of hydrology, covering groundwater, aquifers, precipitation, and mathematical calculations related to water volume and density.

- Sea-Level Changes: This section examines sea-level changes throughout history, particularly focusing on the impact of melting ice sheets on global sea levels.

- American Post-Glacial Flooding: This section explores the massive flooding events that occurred in North America during the post-glacial period, highlighting the Mississippi River as a case study.

- Black Sea Post-Glacial Flooding: This section examines the catastrophic flooding of the Black Sea basin, emphasizing the sudden and dramatic nature of this event.

- Germany’s Post-Glacial Flooding: This section explores the post-glacial flooding events in Germany, analyzing the evidence from river terraces and archaeological sites.

- Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding: This section investigates the extensive flooding that occurred in Britain after the last ice age, focusing on the Thames River as a case study.

- Peat: The Ultimate Evidence: This section highlights the role of peat bogs in providing evidence of past flooding events, including case studies from the Upper Dee and the Somerset Plain.

- Holocene Rivers in Britain: This section analyzes the changes in river systems during the Holocene period, focusing on Welsh river catchments as a case study.

- Discussion of River Avon: This section discusses the specific case of the River Avon, analyzing its evolution and the evidence of post-glacial flooding.

Source 4: “Post-Glacial Flooded Britain v2.1.pdf” (Book)

The content of this source largely overlaps with Source 3 (“Mini Series A5 format – Prehistoric Rivers.pdf”). It provides more detailed case studies and examples, but the core topics and organization remain similar.

Source 5: “Prehistoric Britain – The EPIC TRILOGY that Changed History” (LiDAR Map Collection)

This source focuses on providing LiDAR maps of prehistoric sites in Britain. While not directly contributing to a textual table of contents, these maps can be used to visually enhance the understanding of the topics discussed in the other sources.

Prehistoric Britain: A Study Guide

Short-Answer Quiz

Instructions: Answer the following questions in 2-3 sentences each.

- What is the primary source of water for dew ponds, despite their name?

- How does the presence of snails in archaeological excavations help us understand prehistoric environments?

- What is the significance of a flat-bottomed moat, and what tools were likely used to maintain them?

- According to Langdon, what is the connection between dykes and springs, and why is this significant?

- Why does the author suggest that dykes were likely used as canals, and what evidence supports this claim?

- How do the widths of dyke banks compare to Roman roads, and what does this suggest about their later use?

- What is the meaning of the Dutch word “dijk”, and how is it related to the modern understanding of dykes?

- Explain the concept of groundwater and aquifers and their importance in the water cycle.

- What evidence does Langdon present to challenge the traditional understanding of the formation of river terraces in the Avon Valley?

- Describe the process of peat formation and its significance in understanding post-glacial flooding in Britain.

Short-Answer Quiz Answer Key

- Despite their name, the primary source of water for dew ponds is believed to be rainfall, not dew or mist.

- The presence and types of snail species in archaeological excavations can provide insights into the prehistoric environmental conditions. Certain snail species prefer wet or dry, rocky or grassy environments, helping archaeologists reconstruct past landscapes.

- A flat-bottomed moat is significant because it slows down the natural silting process, prolonging the moat’s usability. Tools like antler picks and cow shoulder blades were likely used to remove silt and weeds.

- Langdon suggests that dykes were intentionally constructed near springs to ensure a continuous water supply. This is significant because it implies that the dykes were designed for water transport, not just defense.

- The author argues that dykes were likely used as canals based on evidence like the presence of water in sections of dykes, their connection to springs, and the discovery of possible prehistoric lock systems.

- Dyke banks are often the same width as Roman roads, suggesting that they were repurposed as roadways after their original function as water channels became obsolete.

- The Dutch word “dijk” refers to both the trench and the bank, reflecting the dual nature of dykes as both excavated ditches and raised earthworks. This highlights their historical use in water management.

- Groundwater refers to water found beneath the Earth’s surface in permeable rock formations called aquifers. Aquifers play a crucial role in the water cycle by storing and releasing water, supporting rivers, wetlands, and providing drinking water.

- Langdon challenges the traditional link between river terrace formation and glacial cycles in the Avon Valley by highlighting the consistent thickness of terraces and suggesting alternative mechanisms like sediment overloading and lateral erosion.

- Peat forms in waterlogged environments through the accumulation of partially decayed vegetation, primarily sphagnum moss. Peat layers in soil profiles provide evidence of past flooding events, helping archaeologists date and understand the extent of post-glacial flooding in Britain.

Essay Questions

- Evaluate Langdon’s argument that many prehistoric dykes in Britain were initially canals used for transportation. What evidence does he provide, and how convincing is his case?

- Discuss the impact of post-glacial flooding on the landscape and environment of prehistoric Britain. How did this flooding affect river systems, vegetation, and human settlement?

- Analyze the various dating methods used by archaeologists to understand prehistoric events, such as radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL). What are the strengths and limitations of these methods?

- Compare and contrast the characteristics of “dew ponds” with the moats found around ancient monuments like Stonehenge. What similarities and differences exist in their construction and purpose?

- Explore the potential connections between prehistoric water management systems, such as dykes and moats, and the development of early settlements and social structures in Britain.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Aquifer: A permeable underground layer of rock or sediment that can hold and transmit groundwater.

- Dew Pond: An artificial pond, typically located on hilltops, primarily fed by rainfall and designed to provide water for livestock.

- Dyke: A linear earthwork consisting of a ditch and a bank, historically used for various purposes including water management, boundaries, and defense.

- Groundwater: Water found beneath the Earth’s surface in the spaces between soil particles and rock formations.

- Holocene: The current geological epoch, which began approximately 11,700 years ago, characterized by a warmer climate and the rise of human civilization.

- LiDAR: (Light Detection and Ranging) A remote sensing technology that uses laser pulses to measure distances and create detailed 3D maps of the Earth’s surface.

- Mesolithic: The middle Stone Age, a period between the Paleolithic and Neolithic characterized by the development of microlithic tools and a shift towards a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

- Moat: A deep, wide ditch surrounding a castle, settlement, or monument, often filled with water for defense or symbolic purposes.

- Paleochannel: An ancient river channel that is no longer active but can be identified through geological or archaeological evidence.

- Peat: A dark, spongy material formed by the partial decomposition of plant matter in waterlogged conditions.

- Post-glacial Flooding: A period of significant flooding that occurred after the Last Glacial Maximum as glaciers melted and sea levels rose.

- Spring: A natural point of groundwater discharge where water flows from an aquifer to the Earth’s surface.

- Terrace: A step-like landform created by the erosion and deposition of sediments along a river valley.

- Wansdyke: A large prehistoric dyke in southwestern England, believed to have been constructed in the 5th or 6th century AD, potentially as a defensive barrier.

FAQ: Prehistoric Britain and Hydrology

1. How did dykes function as waterways in prehistoric Britain, considering they appear dry today?

Contrary to the common perception that these dykes functioned like rivers or Victorian canals, their ability to hold water stems from the presence of groundwater. Groundwater, comprising 30% of the planet’s freshwater, is held within bedrock and soil. Dykes were strategically dug to intersect these groundwater pockets, allowing the ditches to fill naturally. This method even worked on hills and mountains, as groundwater pressure could force water uphill until it reached the surface, where gravity would then take over.

2. What evidence suggests that dykes were used as canals?

Several pieces of evidence point to dykes being used as prehistoric canals:

- Consistent bank width: Dyke banks often have a similar width to Roman roads (5-10m), suggesting a standardized design for transportation.

- Adaptation in dry river valleys: Sections of Offa’s Dyke in dry valleys exhibit features like “ponds” (short dyke segments with water) connected by narrow channels, indicating a potential prehistoric lock system.

- “Smoking gun” water: Excavations of some dykes, even today, reveal water at the bottom, supporting the idea of their function as water-holding structures.

- Sediment analysis: Analysis of sediment layers in dyke ditches reveals patterns of silting and peat formation consistent with fluctuating water levels over time.

3. How did prehistoric people regulate water flow in dykes to overcome changes in elevation?

Prehistoric engineers likely employed simple yet effective techniques to manage water flow:

- Unconnected ditches: By creating small, unconnected ditches, water would remain contained and not flow downhill. Short, shallow connecting ditches could then be cut to allow boats to move between these sections without significant water loss.

- V-shaped weirs: Wooden weirs with small grooves or cuts would allow controlled water flow and boat passage between channels.

- Strategic placement near springs: Dykes were often built near natural springs, ensuring a continuous replenishment of water in the ditch, counteracting losses due to downhill gradient.

4. How did the post-glacial period impact river systems and landscapes in Britain?

The end of the last Ice Age brought significant hydrological changes:

- Massive meltwater discharge: Melting glaciers caused a substantial increase in river discharge, leading to widespread flooding and the creation of extensive river valleys.

- Formation of peatlands: Flooding created vast wetland areas where partially decayed vegetation accumulated, forming peat bogs across the British landscape.

- Sea-level rise: Melting ice sheets led to a global rise in sea levels, submerging coastal areas and altering the courses of rivers.

5. What is the significance of peat in understanding prehistoric hydrology?

Peat bogs act as valuable archives of environmental change:

- Flood indicators: The presence and depth of peat layers indicate periods of flooding and wetland formation.

- Dating tool: Radiocarbon dating of peat provides a chronological framework for understanding the sequence of hydrological events.

- Environmental reconstruction: Analysis of plant and animal remains within peat reveals information about past climates and ecosystems.

6. What evidence suggests that structures like Stonehenge were once surrounded by water?

- Moat-like features: Excavations around Stonehenge reveal large ditches with flat bottoms, characteristic of artificial moats designed to hold water and resist silting.

- Snail populations: Analysis of snail populations within these ditches shows patterns consistent with fluctuating water levels. Specific species thrive in wet, rocky environments, suggesting the presence of both water and the Stonehenge stones.

7. How did prehistoric communities potentially use these flooded landscapes?

Flooded areas provided various resources and opportunities:

- Transportation: Waterlogged valleys and dykes served as navigable waterways for transportation of people and goods.

- Resource access: Wetlands offered abundant food sources like fish and waterfowl.

- Ritual significance: Water held symbolic importance in many cultures, and flooded landscapes may have played a role in religious practices.

8. What are some modern techniques used to investigate prehistoric hydrology?

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging): This remote sensing technology creates detailed topographic maps, revealing subtle landscape features like ancient river channels and dykes.

- Sediment analysis: Studying sediment layers provides information about past water flow, flooding events, and environmental changes.

- Radiocarbon dating: Dating organic material like peat allows for the construction of timelines for hydrological events.

- Mollusca analysis: Studying snail populations helps reconstruct past environments and determine the presence of water in archaeological contexts.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(Britain’s Flooded Past)

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Unlocking the Mysteries of British Prehistory

Delve into the depths of time, as we embark on a captivating voyage into the enigmatic world of British prehistory. www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk is your portal to a treasure trove of archaeological wonders, modern LiDAR reports, and fascinating insights from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy. This immersive digital hub is your key to unlocking the secrets of Britain’s ancient past.

A Glimpse into the Robert John Langdon Trilogy

Step into the shoes of Robert John Langdon, a dedicated explorer of Britain’s prehistoric mysteries. His trilogy, comprising “The Stonehenge Enigma,” “Dawn of the Lost Civilization,” and “The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis,” is a literary marvel that unravels the untold tales of our ancestors. These books take you on an exhilarating journey through time, meticulously researched and backed by over 125 references from esteemed scientists, archaeological experts, and geological researchers.

Dive into the World of LiDAR

At www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, we harness the power of LiDAR technology to unearth hidden landscapes and archaeological marvels. Our LiDAR reports offer a modern lens through which you can peer into ancient history. Explore the effects of flooding on the British environment after the great ice age melt, a phenomenon that has shaped the landscape we see today. Join us in decoding the mysteries of our past using cutting-edge technology.

A Multimedia Experience

Our commitment to storytelling extends beyond the written word. Robert John Langdon has curated a rich multimedia experience, including a YouTube web channel featuring over 100 investigations and video documentaries. These visual journeys complement his classic trilogy, providing a multi-dimensional understanding of prehistoric Britain. From Stonehenge’s construction in 8300 BCE to the lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire known as ‘Silbury Avenue,’ these documentaries offer an immersive experience that brings history to life.

Explore the ’13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in Ancient History’

History is replete with anomalies and enigmas that defy explanation. Robert John Langdon has curated a collection of such historical curiosities in ’13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History.’ These peculiar occurrences and unanswered questions will leave you pondering the mysteries of the past, inviting you to join the debate on their possible interpretations.(Britain’s Flooded Past)

(Britain’s Flooded Past)

More Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Statonbury Camp near Bath - an example of West Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Antonine Wall - Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Mesolithic Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Case Study - River Avon - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Hoax - (Einkorn Wheat) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Reimagining Ancient Rivers: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: From the Rhône to Wansdyke: The Case for a Standardised Canal Boat in Prehistoric Britain - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ivory Tower Collapse: How Academia Abandoned Society – and Took Education, Innovation, and Archaeology Down With It - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Silbury Avenue - Avebury's First Stone Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon's Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: 🛑 The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain's First Monument - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Antler Pick Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnons - An Explainer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Migration Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Offa's Dyke Flipbook - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Subtropical Britain Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Problem with Hadrian's Vallum - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Solved - Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Caerfai Promontory Fort - Archaeological Nonsense - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's First Road - Stonehenge Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals - Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Stone Transportation Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Troy Debunked - Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeological 'pulp fiction' - has archaeology turned from science? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked - Prehistoric Britain