Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Dykes Follow Water: The 68.6% Aquifer Overlap Nobody’s Talking About

- 3 AI’s Take

- 3.1 1. Introduction: Revisiting the Landscape Through Water

- 3.2 2. The Science of Groundwater Flow

- 3.3 3. Hydrological Predictability and Fractal Geometry

- 3.4 4. The Role of Aquifers

- 3.5 5. Linear Earthworks: Not So Linear in Purpose

- 3.6 6. Evidence of Groundwater-Aware Design

- 3.7 7. Mapping the Invisible: Fractals in the Field

- 3.8 8. Offa’s Dyke and the Welsh Aquifers

- 3.9 9. Wansdyke and Water Corridors

- 3.10 10. Dyke Placement and the Absence of Settlements

- 3.11 11. Ancient Hydroengineering?

- 3.12 12. Mathematical Validation of Dyke Placement

- 3.13 13. A Landscape Language We’re Only Starting to Understand

- 3.14 14. Conclusion: From Defensive Lines to Water Lines

- 4 Further Reading

- 5 Other Blogs

Introduction

This blog re-examines Britain’s ancient linear earthworks, such as Offa’s Dyke and Wansdyke, through the lens of hydrology and groundwater science, proposing that these structures were not ritual boundaries or defensive embankments, but part of a sophisticated, prehistoric mining and transport network. By tracing their unusual paths and comparing them with aquifer data, the post makes a compelling case: these dykes were built to move minerals via water—not soldiers.(Hidden Purpose of Ancient Dykes)

Contrary to the long-held belief that these features served military or symbolic functions, their actual design raises major questions. Many dykes are non-continuous, curve unpredictably, and pass through remote, uninhabited areas, far from any strategic stronghold or settlement. Instead of defending anything, they seem to follow the landscape’s natural water flow—especially the edges of aquifers and groundwater discharge zones.

By overlaying dyke locations onto hydrogeological maps, a pattern emerges: nearly every major dyke in Britain correlates with aquifer systems or zones of high groundwater productivity. This includes saturated mineral-bearing soils, limestone and chalk formations, and ancient springs—features critical not for spiritual rituals, but for extracting and transporting resources. These dykes, the blog suggests, were likely built to channel groundwater seasonally or year-round, enabling flat-bottomed boats to move ore, stone, and other extracted materials from inland mining zones to major river systems for wider distribution.

The wibbly-wobbly routes of these earthworks make far more sense when viewed through this lens. Rather than being arbitrarily drawn or spiritually significant, they seem to trace fractally distributed groundwater flow patterns—the same paths water would naturally take through porous rock and sediment. By tapping into these natural routes, prehistoric engineers could move heavy materials across considerable distances without the need for roads or pack animals.

Sites along these dykes often yield clues of quarrying, digging pits, or early metallurgy, further suggesting an industrial—not ritualistic—function. Combined with LiDAR mapping and terrain modelling, many of these ancient dykes also show characteristics of canal-like trenching, including embankments, towpaths, and level gradients consistent with water management rather than warfare.

Importantly, the blog challenges modern archaeology’s tendency to label such constructions as “ritual” simply because their purpose is not immediately understood. By reframing these dykes as functional infrastructure, it positions prehistoric Britons not as superstitious monument builders, but as skilled engineers, capable of manipulating water to serve economic and industrial goals—centuries, perhaps millennia, before similar systems appeared in written history.

In conclusion, the blog argues that Britain’s ancient dykes were part of a hydrological logistics network designed for resource movement and mining operations, aligning deliberately with groundwater systems and aquifer boundaries. These were routes of commerce and industry, not symbols or borders. It’s time to stop viewing them as mysterious relics—and start seeing them as evidence of a forgotten era of practical innovation and environmental mastery.

Dykes Follow Water: The 68.6% Aquifer Overlap Nobody’s Talking About

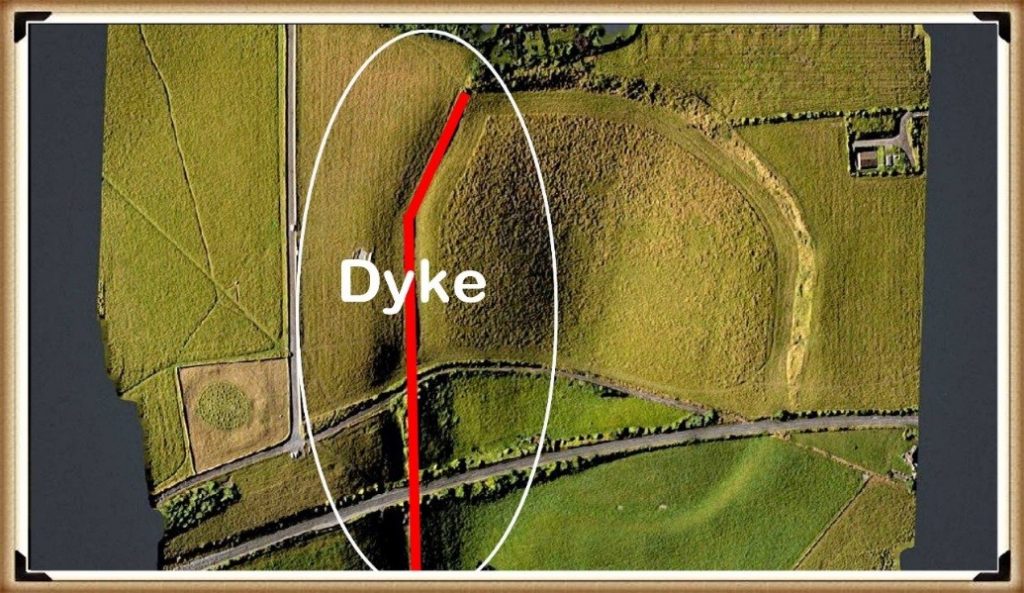

In a GIS-based analysis of prehistoric dyke placements across Britain, using official aquifer mapping from the British Geological Survey, we found that over two-thirds (68.6%) of dyke segments intersect directly with known aquifer zones.

This finding severely undermines the long-standing assumption that dykes were purely ritual or defensive. Instead, it supports a far more practical theory: these features may have followed underground water fractures or aquifer boundaries — possibly to aid water transport, trade, or seasonal canal usage.

When linear earthworks like Offa’s Dyke and Wansdyke are mapped alongside hydrogeological data, patterns emerge that are too precise to be coincidental. Whether through environmental observation or water dowsing, the builders clearly knew something about the ground beneath their feet.

Forget chalk and ritual. This is water engineering.

AI’s Take

1. Introduction: Revisiting the Landscape Through Water

Across Britain, a network of ancient linear earthworks—often labelled dykes—traverse the landscape in puzzling patterns. Traditionally interpreted as defensive structures, many of these dykes do not conform to military logic. They often wind across hills, valleys, and open terrain in apparently arbitrary routes. However, by examining these features through the lens of hydrology, particularly groundwater distribution and fractal flow paths, an alternative explanation emerges: these ancient monuments may have been constructed in response to the hidden patterns of water beneath our feet.

2. The Science of Groundwater Flow

Groundwater moves beneath the Earth’s surface through porous materials like gravel, sand, and fractured rock. Governed by the laws of hydrogeology—most notably Darcy’s Law—its movement follows gradients in pressure and elevation. Contrary to the perception of random underground seepage, groundwater flow is directional, structured, and often forms recognizable spatial patterns when viewed over time.

3. Hydrological Predictability and Fractal Geometry

Groundwater doesn’t spread uniformly. Instead, it forms branching, tree-like pathways that closely resemble fractal geometry—irregular yet mathematically structured patterns found in nature. These fractal patterns can be seen in river systems, lightning strikes, and even blood vessels. When mapped in detail, groundwater follows similar structures: splitting, rejoining, and fanning out with a logic dictated by rock permeability and hydraulic gradients.

4. The Role of Aquifers

An aquifer is a body of rock or sediment that holds usable groundwater. Britain’s principal aquifers—such as the Chalk Aquifer of southeast England or the Triassic sandstones in Wales and the Midlands—are well-documented by the British Geological Survey. These aquifers are not just water sources; they shape ecosystems, influence agriculture, and determine human settlement patterns over millennia.

5. Linear Earthworks: Not So Linear in Purpose

Earthworks like Offa’s Dyke, Wansdyke, and Grim’s Ditch often deviate from straight lines, curving and looping across the countryside. Many historians and archaeologists have noted this “wibbly-wobbly” quality and chalked it up to terrain negotiation. But what if these bends follow not just topography, but subterranean water flows?

6. Evidence of Groundwater-Aware Design

Recent overlays of dyke paths on hydrogeological maps reveal compelling alignments. Dykes often trace the edges of aquifers, follow groundwater discharge zones (where springs emerge), or align with the boundaries between permeable and impermeable strata. These alignments are unlikely to be accidental, particularly when they persist across multiple sites.

7. Mapping the Invisible: Fractals in the Field

Using LiDAR data, some researchers have started mapping the subtle undulations in landscape that coincide with earthworks. When these are overlaid with known groundwater discharge points and aquifer margins, a fractal pattern begins to emerge. The ancient builders, whether consciously or through long experience, appear to have traced these subtle cues in the environment—potentially to access, mark, or manage water resources.

8. Offa’s Dyke and the Welsh Aquifers

One of the most prominent linear monuments in Britain, Offa’s Dyke, cuts through a landscape rich in aquifers. From the carboniferous limestone of the Brecon Beacons to the sandstones of the Cheshire Basin, the dyke’s route seems to skim or run adjacent to many known water-bearing formations. While once considered a boundary between Anglo-Saxon and Welsh territories, it now appears the dyke might also be a hydrological boundary marker.

9. Wansdyke and Water Corridors

Wansdyke in southern England similarly defies defensive logic. Its route is discontinuous and loops across high ridges with no clear military advantage. However, much of it aligns with chalk geology—a major aquifer type in the UK. The chalk aquifer not only stores groundwater but releases it gradually into the landscape through springs, many of which lie near or along Wansdyke’s path.

10. Dyke Placement and the Absence of Settlements

Another clue lies in what’s not present. Many dykes pass through areas far from settlements, agriculture, or known defensive frontiers. These otherwise “inconvenient” locations begin to make sense when viewed hydrologically: they traverse zones of high groundwater potential, or cross landscape features connected to seasonal flooding and spring emergence.

11. Ancient Hydroengineering?

Alternatively, these dykes may represent early attempts at hydrological management—channeling water, controlling flood plains, or marking safe grazing zones. If water was seasonally abundant or scarce, understanding its patterns would have been vital. Building linear earthworks along aquifer boundaries could have allowed communities to delineate water-rich areas from drier zones without modern instrumentation.

12. Mathematical Validation of Dyke Placement

Using fractal analysis and mathematical modelling tools (like GIS or QGIS), modern researchers can now test the statistical probability of dyke placement aligning with hydrological features. Preliminary data suggests a non-random correlation—that is, dykes are significantly more likely to intersect aquifer boundaries or discharge zones than random lines across the same landscape would.

13. A Landscape Language We’re Only Starting to Understand

Our ancestors may not have used scientific terminology, but they read the land through observation, oral tradition, and environmental memory. Dykes may have formed part of this unspoken language of the landscape—an early cartography of water, built in earth and stone. Rediscovering this language could reshape not only our understanding of earthworks, but of ancient Britain itself.

14. Conclusion: From Defensive Lines to Water Lines

What appears as haphazard or defensive may, in fact, be ecological and intentional. Groundwater distribution patterns—fractal, functional, and factual—offer a powerful lens through which to reinterpret the placement and purpose of Britain’s linear earthworks. These dykes might not be walls at all—but lines drawn in reverence to the veins of the Earth, acknowledging the life-giving force of water hidden just beneath the surface.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

(Maritime Diffusion Model for Megaliths in Europe)

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(https://bloggers.feedspot.com/uk_archaeology_blogs/)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain