Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

Contents

- 1 1. Introduction — The Forgotten Phase

- 1.0.1 2. How We Know Stonehenge Phase 1 Was Built in 8300 BCE

- 1.0.2 3. Layout and Function — The Real Purpose of the Site

- 1.0.3 4. The Bluestones — Transport, Composition, and Use

- 1.0.4 5. The Water — How It Worked, and Why It Mattered

- 1.0.5 6. The Evidence of Reuse and Replacement

- 1.0.6 7. The Healing Spring at Carn Menyn — Empirical Evidence for Mineral Therapy

- 1.0.7 8. The Pallisade and the Silent Towers

- 1.0.8 9. Decline and Transition to Phase 2

- 1.0.9 10. Conclusion — A Monument Built on Function, Not Fantasy

- 2 PodCast

- 3 Author’s Biography

- 4 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 5 Further Reading

- 6 Other Blogs

1. Introduction — The Forgotten Phase

Most people imagine Stonehenge as the great sarsen trilithons. In fact, those belong to Phase 2, constructed around 4300 BCE. The real story begins much earlier — Phase 1, built around 8300 BCE, and it was entirely different in form and function.

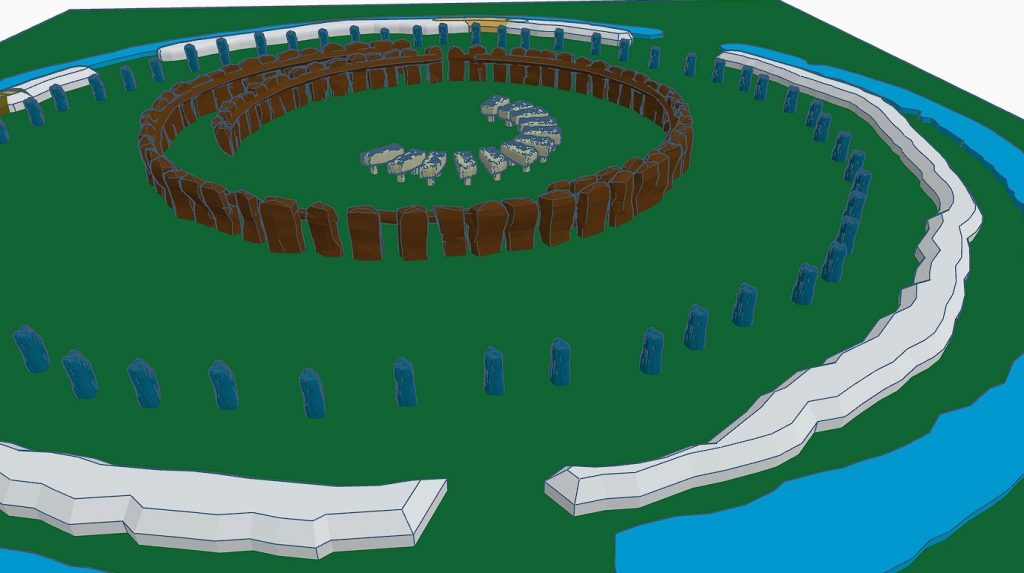

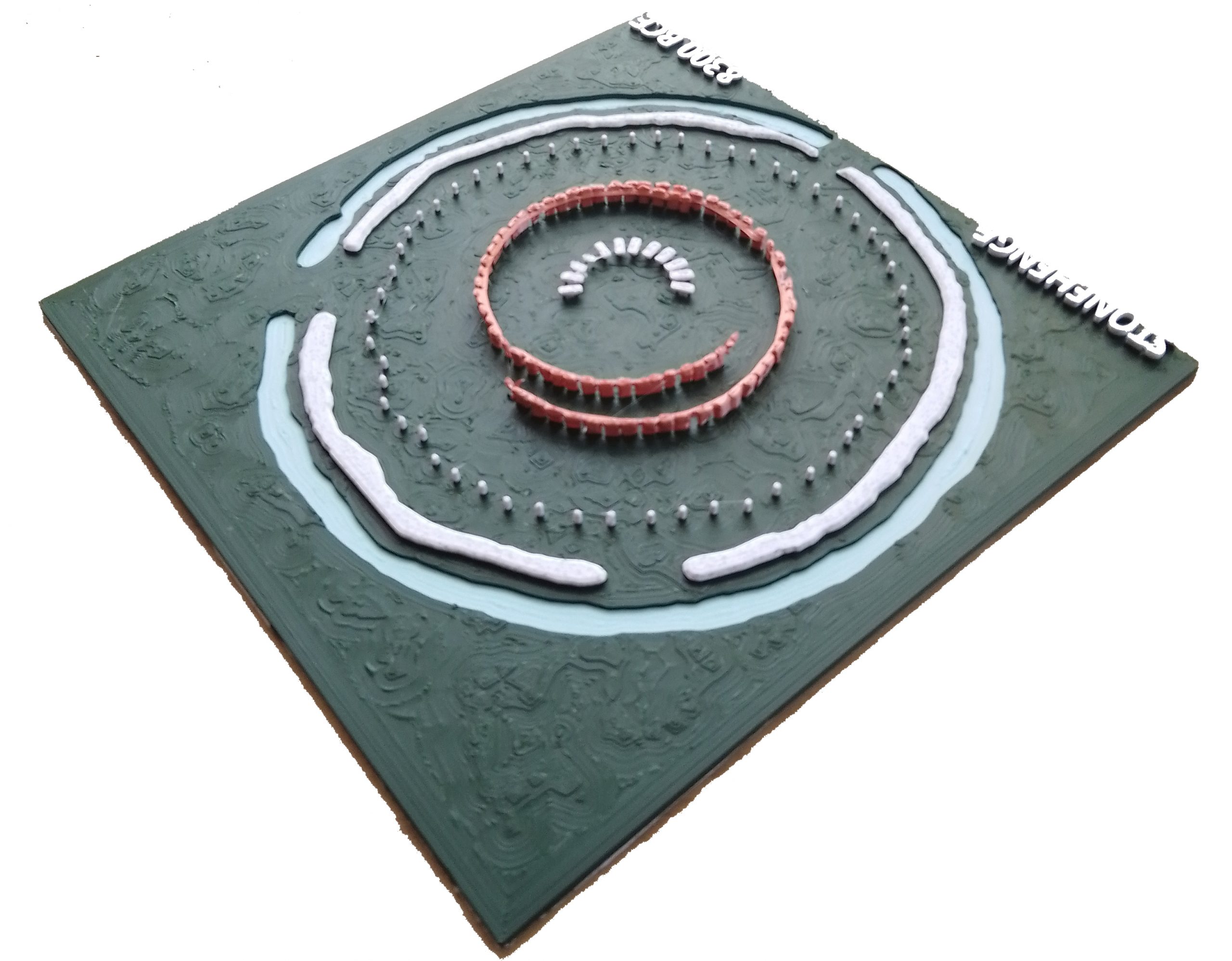

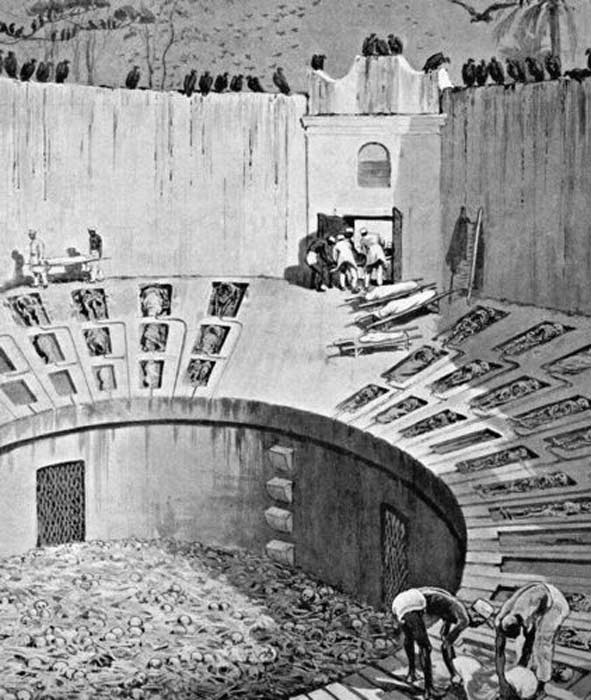

This earliest version of Stonehenge was a working health and mortuary site. It featured a chalk-cut moat that held water, 58 imported Preseli bluestones, and a timber palisade enclosing raised stone platforms for excarnation. Birds were allowed to clean the dead — a practice still seen today in India’s towers of silence. The Y and Z holes marked the outer limits of the palisade; the Q and R holes defined where excarnation slabs once stood. The entire setup was pragmatic, not ritualistic.

2. How We Know Stonehenge Phase 1 Was Built in 8300 BCE

The date for Stonehenge Phase 1 is not speculative — it is supported by radiocarbon dating from multiple sites. Charcoal samples from postholes discovered in the Stonehenge car park excavation have been dated to around 8300 BCE. This corresponds closely with two quarry sites in the Preseli Hills of Wales, where evidence of human activity — including hearths associated with stone extraction — has also produced C14 dates from the same period. These sites are not random campfires but appear to be linked directly to quarrying activity associated with the bluestones.

This level of coordination between quarrying and monument construction suggests an advanced society operating across hundreds of miles, capable of planning and logistics long before the Neolithic. The matched radiocarbon dates from the quarry and monument provide strong empirical support for the theory that bluestones were transported and erected at Stonehenge in the 9th millennium BCE.

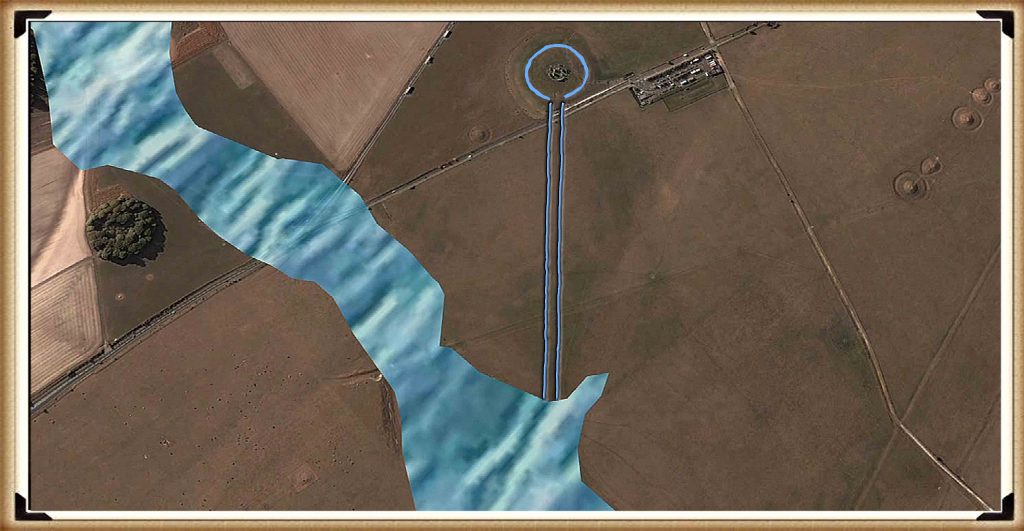

While hydrological modelling still reinforces the idea that this was the only period when the chalk aquifer would have provided a permanent water source at the monument, it is the radiocarbon evidence — independently dated at both source and site — that fixes Stonehenge Phase 1 to approximately 8300 BCE. This makes it the earliest scientifically verified monumental construction in the British Isles.

3. Layout and Function — The Real Purpose of the Site

The layout of Phase 1 was deliberate and practical. At the centre were the Q and R holes, which supported dolmen-style excarnation slabs — single flat stones balanced precisely on pointed supports to deter rodents. These slabs were used to expose bodies to the elements and scavenger birds, an efficient and sanitary method of processing the dead. The palisade surrounding the structure, marked by the Y and Z holes, enclosed this inner space to protect the area while allowing avian access. The design shows a clear understanding of decomposition cycles and scavenger behaviour.

The northwest orientation of the Q and R hole alignment corresponds to the moon’s setting position, reinforcing the functional connection to death and timing. The number of bluestones — 58 — was not arbitrary. It matches the synodic cycle of the moon, used to track its 18.6-year cycle of eclipses and nodal variation. This was likely vital for excarnation timing, navigation, tidal awareness, and critical knowledge for a riverine trading society.

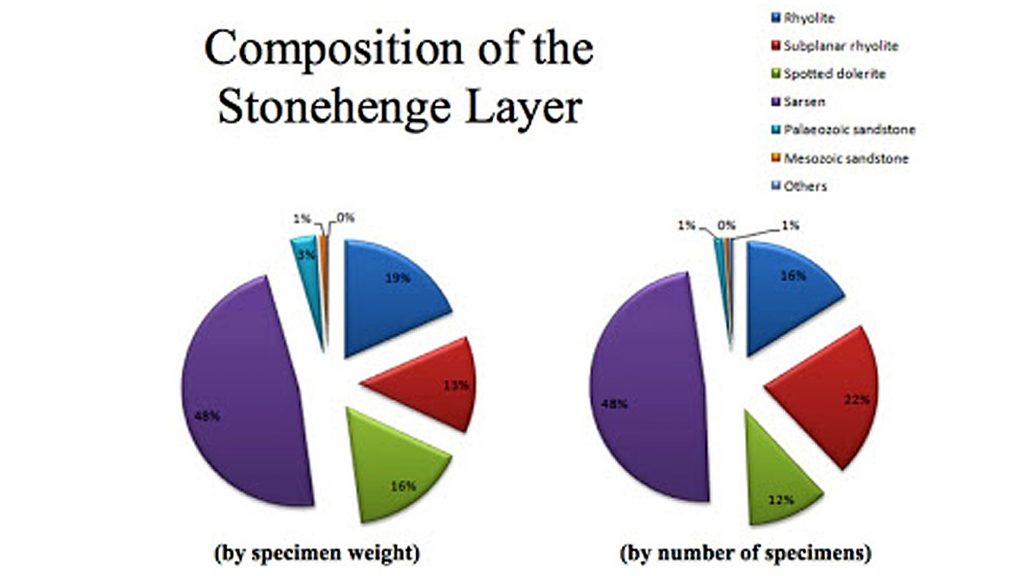

The bluestones themselves were never meant to remain intact. As noted by Darvill and Wainwright, the bluestones were chipped down almost immediately. Over 3,675 fragments have been discovered — a remarkable total given that only half the site has been excavated. These fragments were deliberately introduced into the chalk moat. With their high rock salt content, the bluestone chips enriched the water with medicinal minerals, enhancing its curative potential. This suggests that Stonehenge Phase 1 was not a ceremonial temple, but a sophisticated facility for managing death, disease, and recovery.

4. The Bluestones — Transport, Composition, and Use

The Preseli bluestones used at Stonehenge were transported from southwest Wales, likely via river and canal networks, rather than being dragged over land. The discovery of an ancient prehistoric catamaran boatyard dating to the Neolithic in Wales suggests they were moved by double-hulled craft suitable for carrying heavy loads. Britain’s river levels were significantly higher at the time, which enabled direct water transport to the site without the need for sea voyages.

What matters more than their origin is their composition. The Preseli stones are rich in rock salt, copper, and trace minerals, which leach into water when submerged or broken. This is not theoretical — over 3,675 bluestone fragments have been found in the moat area. This suggests the stones were intentionally broken up to release minerals into the water, creating a kind of early mineral spa.

This theory is further supported by Darvill and Wainwright, who observed that the stones were being chipped away from the time of their erection and even proposed the site may have served as a healing centre. This evidence strengthens the argument that Stonehenge functioned primarily as a public health structure, specifically for sepsis and infection, the leading causes of death in prehistoric times.

5. The Water — How It Worked, and Why It Mattered

The chalk-cut ditch surrounding the central enclosure was not ornamental. It was a functional water feature, drawing from a naturally high water table during the Mesolithic. The aquifer-fed ditch would have constantly circulated mineral-rich water through the site, turning the enclosed area into a therapeutic environment.

Bluestone chippings, deliberately broken and deposited in this moat, would have slowly released rock salt and trace elements into the water. Salt has antiseptic properties and is still used today in wound care. Soaking in this solution could have helped prevent or treat infections in a world without antibiotics.

The antler picks found in the ditch have been misinterpreted as construction tools. In fact, they are more logically explained as dredging tools used to maintain the flow and clarity of the water system. These were found in later layers, suggesting periodic cleaning of the moat rather than its original excavation.

6. The Evidence of Reuse and Replacement

Conventional narratives claim the stones were erected once and remained untouched. However, C14 dating and excavation records tell a different story. The bluestones were replaced multiple times over a long period, not just transported once and left to stand. Dating of stone socket fills shows repeated insertion events, sometimes centuries apart.

This supports the idea that the site was actively maintained, not abandoned or commemorated. Replacement intervals appear tied to mineral depletion — once enough salt and trace minerals had leached out of the existing stones, they were broken up and replaced. This explains the high number of fragments despite limited excavation.

With only around 50% of the site dug, over 3,600 fragments have been recovered — meaning the actual number is likely double. These are not random breakages or damage from collapse; they were systematically chipped and deposited into the water.

7. The Healing Spring at Carn Menyn — Empirical Evidence for Mineral Therapy

A major criticism of the “healing stones” hypothesis has been the supposed lack of empirical evidence. But recent research at Carn Menyn in the Preseli Mountains — one of the key sources of the Stonehenge bluestones — reveals a now-dry sacred springhead that may hold the key to understanding the stones’ original purpose.

Gordon Freeman’s 2013 fieldwork identified a collapsed cromlech and associated cairn built directly over a once-flowing freshwater spring known locally as Pen y Tarddiant Sanctaidd (Holy Springhead). This spring fed a stone-lined stream channel called Rhestr Gerrig (“Stone Row”), wounding through the landscape toward a marshy area called Fat Hazelnut Bog. While this water source has since dried up, its historical importance is undeniable. The spring was sacred enough to warrant a formal burial monument, and the fact that a cromlech capped it suggests a long tradition of ritualised — and likely therapeutic — use.

But this is more than symbolic. The springhead sits directly within the geological formation from which spotted dolerite (bluestone) was quarried — and critically, analysis of this dolerite reveals it contains natural rock salt and trace minerals. This means the spring water would likely have been slightly brined, absorbing salts and mineral ions as it passed through and over the bluestone deposits. Wound irrigation with mineral water would have had antiseptic and soothing properties — a fact observable by prehistoric peoples even without modern biochemistry.

This context gives physical, testable logic to why the same rock was selected and transported over 200 km to the chalk aquifer basin of Stonehenge: to recreate the medicinal properties of the Preseli spring. The deliberate chipping of bluestones into fragments and depositing them into the moat — as confirmed by Darvill and Wainwright — wasn’t ceremonial destruction. It was chemical replication. The stones infused the water with trace minerals, producing a brine bath system that matched the healing waters of the original spring in Wales.

Taken together — the presence of a prehistoric sacred spring, the saline-rich composition of bluestone, and the evidence of engineered mineral dissolution at Stonehenge — make this a rare case where archaeology, geology, and hydrology converge into an empirical explanation for a so-called “ritual” monument. Stonehenge Phase One was not a temple. It was Britain’s first public health sanctuary, and the spring at Carn Menyn was its biochemical blueprint.

8. The Pallisade and the Silent Towers

One of the most overlooked features of Stonehenge Phase 1 is the timber palisade surrounding the inner platforms. This structure wasn’t defensive — it was functional and hygienic, containing excarnation within the central area while restricting access.

This enclosure is clearly defined by the Y and Z holes, which are too consistent and evenly spaced to be symbolic. They formed the foundation for a pair of stone uprights, making the interior a raised series of protected platforms. Birds — especially carrion feeders (mainly Jackdaws, Ravens, and Crows)— were allowed access to clean the bodies. The cleaned bones were then taken to nearby Long Barrows for entombment.

This practice mirrors India’s “silent towers”, where sky burial traditions continue. It reflects a belief not in symbolism but in natural decomposition and purification. Stonehenge’s setup provided a sanitary, repeatable method for body disposal — highly advanced for its time.

9. Decline and Transition to Phase 2

Over time, the water table dropped as the aquifer drained and post-glacial rebound altered the landscape. The once-functioning moat began drying up, and the mineral bath lost efficacy. This environmental shift marks the end of Phase 1 and the beginning of a new chapter in the site’s life.

The bluestones were gradually replaced by larger sarsen stones, marking a transition from a practical medical site to something more monumental. These sarsens were installed around 4300 BCE, beginning what most people today incorrectly consider the start of Stonehenge.

This change is visible in the construction of The Avenue, a wide processional route that leads away from the original riverfront location to the new shoreline further northeast. This redirection reflects both cosmic alignments and the simple reality of hydrological change.

10. Conclusion — A Monument Built on Function, Not Fantasy

The first phase of Stonehenge was not a mystical temple, a ceremonial gathering place, or a stone calendar. It was a public health structure, grounded in the harsh realities of Mesolithic life — infection, injury, and death. Its foundation wasn’t spiritual conjecture, but practical science: built on a prehistoric shoreline, maintained by a saturated aquifer, and enriched by mineral-laden bluestone chips dissolved into the water. It was a place of triage, treatment, and transformation.

Thanks to a new mathematical dating model — one grounded in radiocarbon evidence from quarry hearths, site postholes, and hydrological mapping — we now know Phase 1 began around 8300 BCE. This places Stonehenge among the oldest monumental structures in Europe, second only to Carnac in France, and dismantles the false timeline held by mainstream archaeology. It was not a late Neolithic curiosity but a pioneering Mesolithic achievement. And this was a rational, functional innovation centuries ahead, unlike the speculative calendars or solar temples peddled by tradition.

Archaeologists have consistently failed to interpret key features of the site. Once thought irrelevant, the postholes forming the central crescent pattern align exactly with where excarnation slabs would have stood. Their curious shape and placement remain unacknowledged in academic literature. Even the surrounding palisade, indicated by the Y and Z holes, has gone largely ignored, despite its obvious protective function. Traditionally described as ceremonial, the ditch is no ditch at all — it is a ring of pits, designed to house seating platforms below water level for therapeutic bathing. This unique design, found nowhere else in Britain, is left undiscussed because it breaks too many taboos about what Stonehenge might truly have been.

The fog is lifting with advances in LiDAR, mineral analysis, hydrology, and radiocarbon calibration. Stonehenge Phase 1 must now be recognised as Britain’s first scientific structure — a masterpiece of Mesolithic engineering, biology, and community medicine — misunderstood for thousands of years by a profession still reluctant to let go of fantasy.

PodCast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?