What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 1. Why This Blog Exists

- 3 2. The Data Nobody Had Ever Assembled

- 4 3. What Counts as Water Evidence

- 5 4. The Numbers That Break the Model

- 6 5. Percentage, Not Just Presence

- 7 6. Control Boreholes

- 8 Control conclusion

- 9 7. Case Study: R16 Counted Properly

- 10 Step 5: Calculate frequency (events per metre)

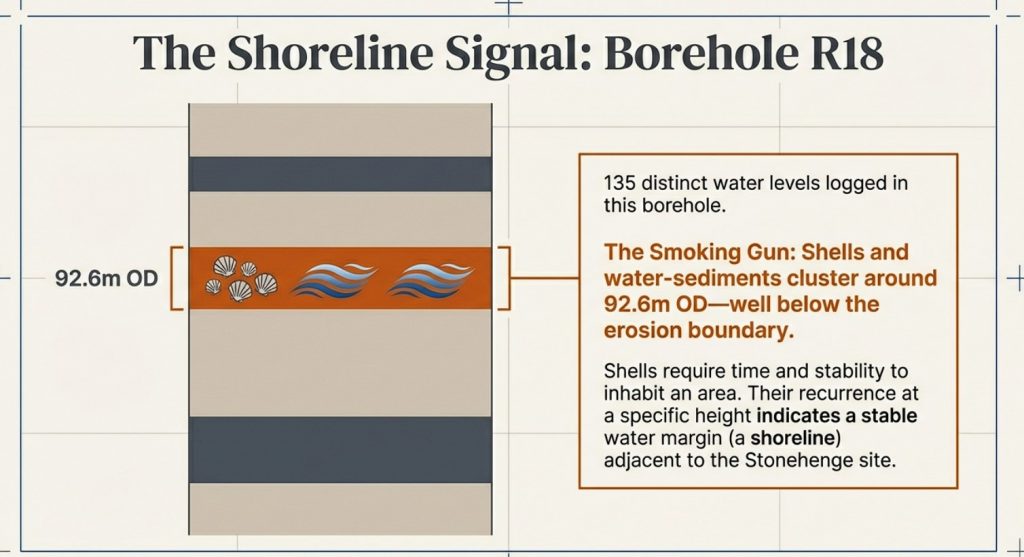

- 11 8. Case Study: R18 and the Shoreline Signal

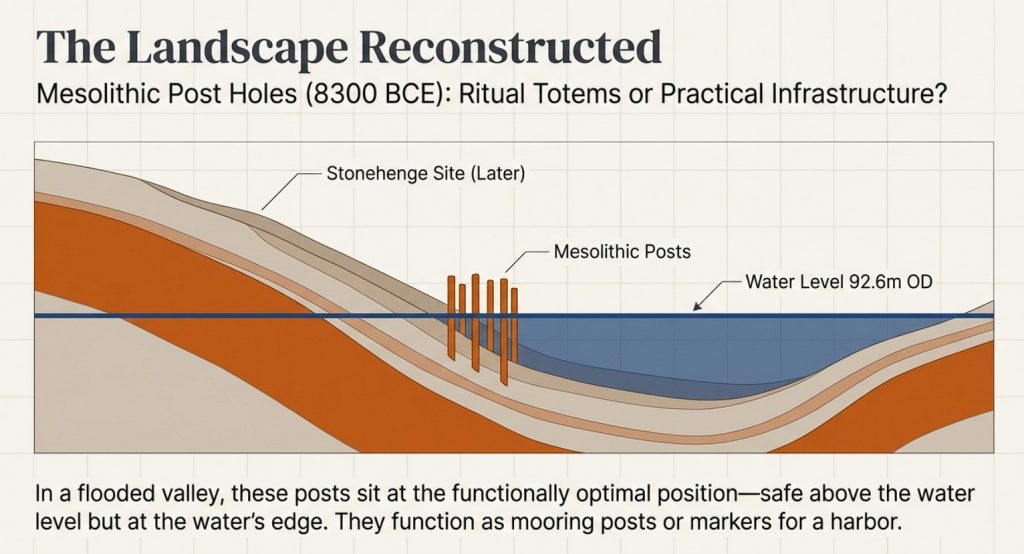

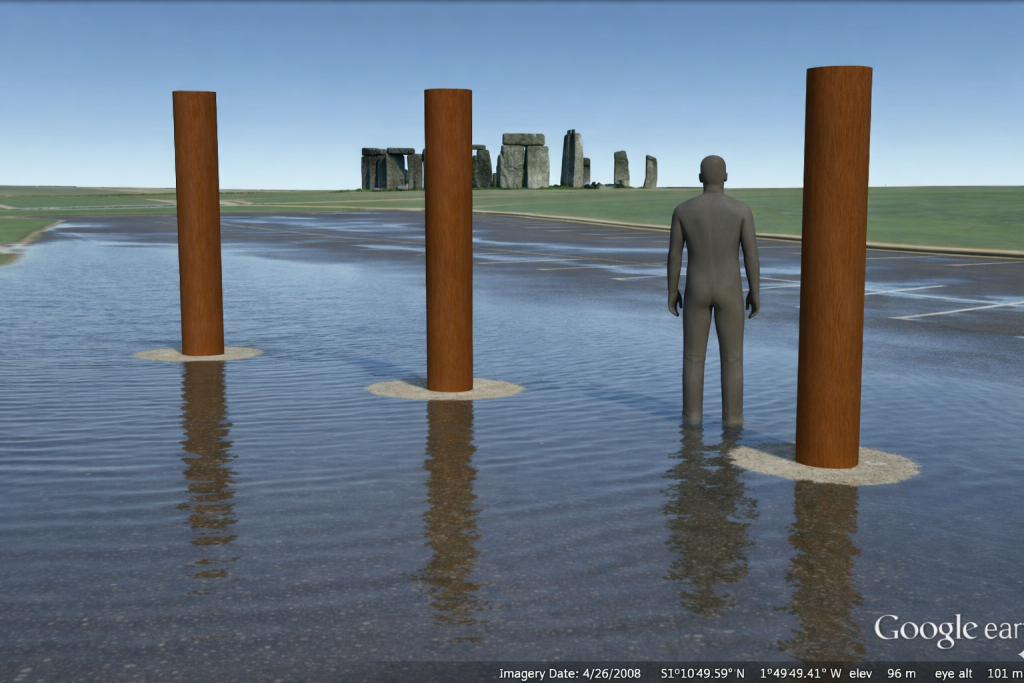

- 12 9. The Mesolithic Posts Reinterpreted

- 13 10. The Periglacial Escape Route Fails

- 14 11. Why the “Older Ice Age Valley Fill” Argument Also Fails

- 15 12. Locking into the Wider System

- 15.1 River terraces, meltwater volume, and scale

- 15.2 River terraces are volume records, not abstractions

- 15.3 Why terrace height matters more than terrace age

- 15.4 Re-evaluating Ice Age scale

- 15.5 Why Stonehenge Bottom sits where it does

- 15.6 Linking local depth to the regional scale

- 15.7 Why this matters for interpretation

- 15.8 Scale closes the loop.

- 16 13. What This Forces Archaeology and Geology to Confront

- 16.1 Archaeology’s problem: interpretation without ground conditions

- 16.2 Geology’s problem: description without measurement

- 16.3 The disciplinary gap that allowed this to persist

- 16.4 Why this is not an attack on expertise

- 16.5 What changes from here on

- 16.6 Stonehenge as a test case, not an exception

- 16.7 The final position

- 16.8 Because of the huge amount of data and this blog being over 6000 words, PART II, with all the technical data, including all boreholes, will be published next week.

- 17 Podcast

- 18 Author’s Biography

- 19 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 20 Further Reading

- 21 Other Blogs

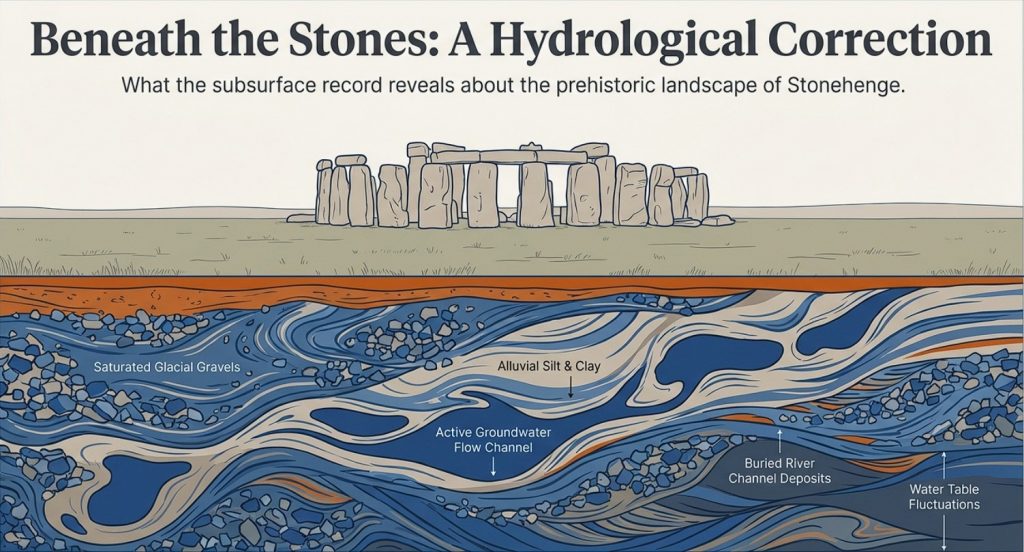

Introduction

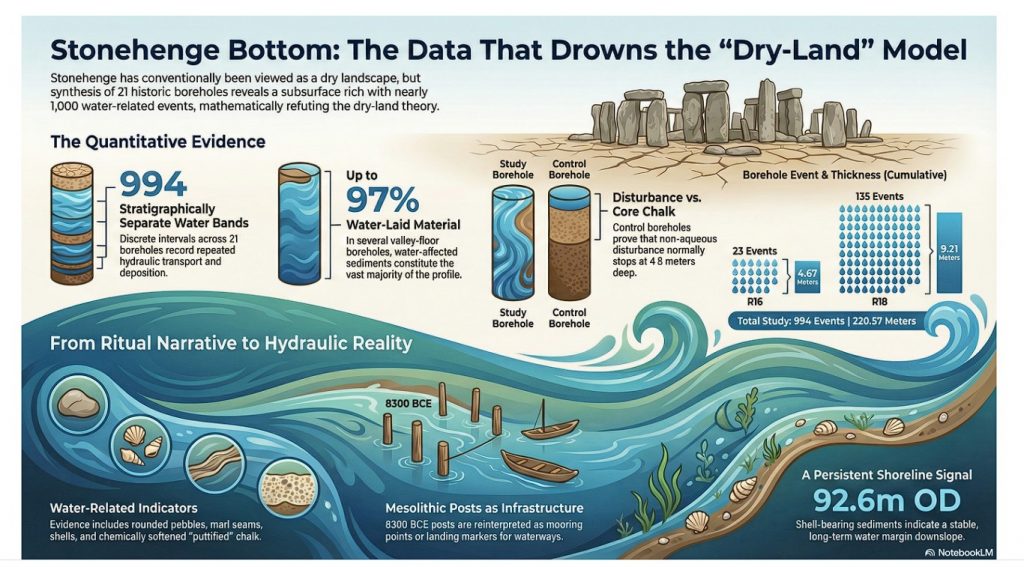

For more than a century, Stonehenge has been interpreted as if it were constructed in a dry, stable chalk landscape, with water treated as peripheral or incidental. That assumption has never been tested against the subsurface record at the landscape scale. This blog presents the results of the first complete synthesis of borehole data from around Stonehenge Bottom, linking 21 historic boreholes into a single, quantitative framework. The outcome is neither interpretative nor theoretical. It is numerical. The subsurface record demonstrates repeated, extensive, and spatially constrained water activity throughout the Holocene, fundamentally incompatible with a dry-land model for early Stonehenge. What follows is not a reinterpretation of Stonehenge — it is a correction driven by data that has been available for decades but never assembled, counted, or tested as a system. (What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge)

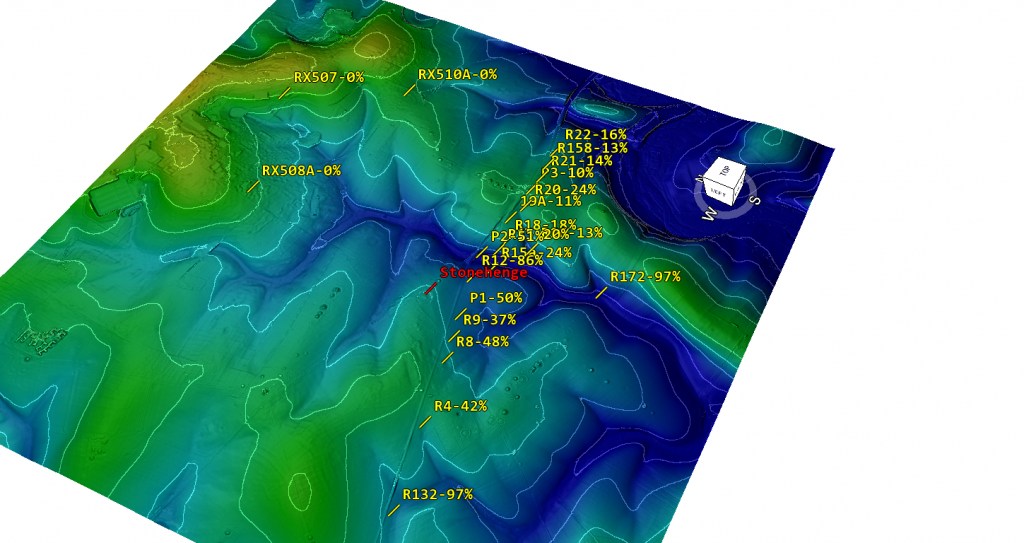

Video showing the volume of River material as a percentage of the Borehole

1. Why This Blog Exists

From surface narratives to subsurface evidence

Stonehenge interpretation has long been dominated by surface observations: earthworks, stone settings, artefact distributions, and visual landscape relationships. These are valuable, but they are incomplete. Landscapes do not function at the surface alone, and water — in particular — leaves its most durable evidence below ground.

The central problem addressed here is simple: claims about a dry Stonehenge landscape have been made without reference to the subsurface record that would be required to support them. Boreholes have existed around Stonehenge for decades, logged by multiple contractors for engineering and infrastructure projects, yet they have almost never been synthesised or quantified in archaeological interpretation.

This blog exists because that synthesis has now been done.

By analysing boreholes not as isolated descriptions but as a connected dataset — counted, measured, and compared across topography — it becomes possible to test whether Stonehenge Bottom behaved as a dry chalk valley or as a water-dominated basin during the Holocene. Once that question is asked using arithmetic rather than narrative, the answer is no longer ambiguous.

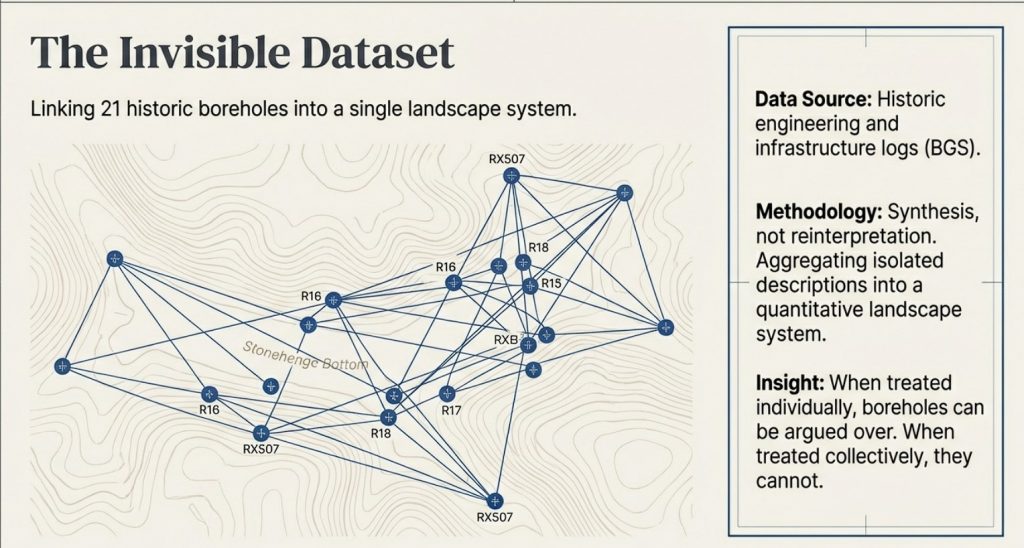

2. The Data Nobody Had Ever Assembled

Linking 21 boreholes into one landscape system

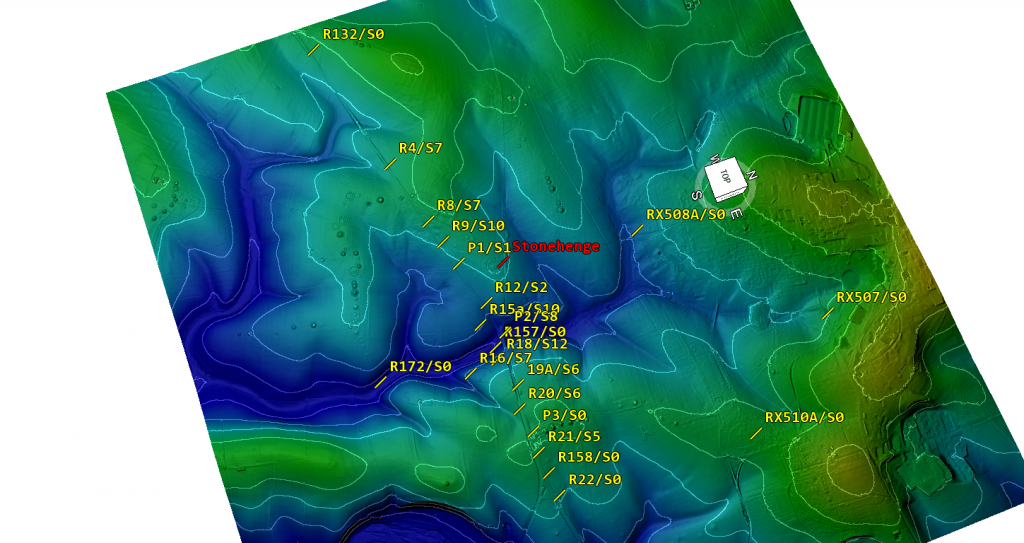

Boreholes around Stonehenge Bottom are not new. Many were drilled decades ago for engineering, infrastructure, and site investigations. What is new is that they have now been brought together and analysed as a single landscape-scale dataset, rather than as isolated, descriptive records.

Historically, each borehole has been treated as local and incidental — a column of chalk, a few notes on gravel or marl, then filed away. No attempt was made to ask whether these records, taken together, described a coherent subsurface environment. As a result, interpretations of the Stonehenge landscape were based almost entirely on surface evidence, while the subsurface record remained fragmented and effectively invisible.

That fragmentation is the core problem this section resolves.

Twenty-one boreholes distributed around Stonehenge Bottom and the adjacent valley system have now been collated, normalised, and analysed together. They span the valley floor, margins, and surrounding uplands. They were logged by different contractors, at different times, for different purposes — which makes their convergence more significant, not less.

Crucially, the analysis does not rely on reinterpretation of the logs. No lithologies were renamed. No depths adjusted. No categories merged to strengthen an argument. Each borehole was taken exactly as recorded, then subjected to the same fixed rules for identifying water-related evidence.

When treated individually, these boreholes can be argued over.

When treated collectively, they cannot.

Once counted, measured, and compared across topography, a clear and repeatable pattern emerges: water-related features are vertically stacked, repeatedly logged, and concentrated within the valley, while the surrounding high ground shows a fundamentally different subsurface character. That pattern only becomes visible when the data are assembled as a system.

This section establishes the foundation for everything that follows. The argument does not depend on a single “key” borehole, nor on selective examples. It rests on the behaviour of the dataset as a whole, which is precisely why it has such force.

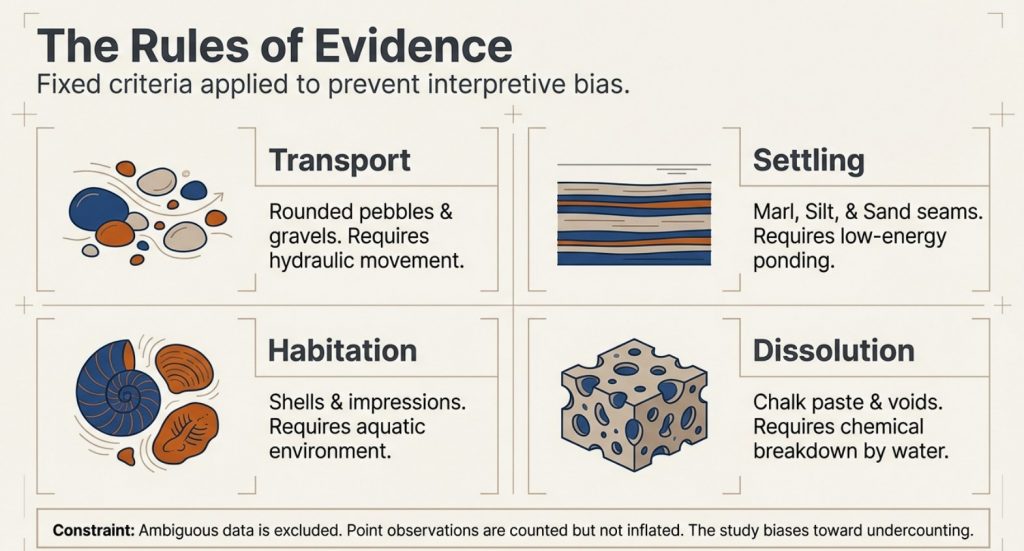

3. What Counts as Water Evidence

Rules fixed in advance

Before any counting was undertaken, the rules had to be fixed. This matters because most disagreement in geo-archaeology does not arise from missing data, but from changing definitions once results are known.

In this analysis, a water-related occurrence is defined strictly as any logged interval that requires water to exist, or to have existed, in order to form or to be preserved. Nothing is inferred. Nothing is upgraded. Only what is explicitly recorded in the borehole logs is used.

The following categories are considered water-related evidence, with reasons provided.

→ Rounded pebbles, gravel, and cobbles

Rounded or sub-rounded clasts require transport. In chalk landscapes, this transport is hydraulic. Angular flint fragments may occur residually; rounded gravels and cobbles do not. Where gravels are logged as lenses, bands, or stacked horizons, they indicate repeated water movement, not isolated disturbance.

→ Flint gravel bands, flint lags, and sheeted flint horizons

Flint concentrated into bands or sheets reflects winnowing, reworking, or lag formation by flowing or standing water. These features cannot be produced by in situ chalk decay alone and require hydraulic sorting.

→ Sand, silt, and marl seams

Fine-grained sediments such as sand, silt, and marl are, by definition, water-laid. Their presence within chalk sequences indicates periods of low-energy flow, ponding, or suspension settling. Repeated marl seams imply repeated water presence over time, not a single episode.

→ Shell material (intact shells, fragments, and shell-rich horizons)

Shells indicate habitable aquatic environments. They require sustained water conditions, not transient wetting. Their repeated occurrence at multiple depths is incompatible with surface wash or periglacial disturbance.

→ Shell impressions and moulds (dissolved shells)

In chalk aquifers, shells dissolve readily under percolating freshwater, often leaving impressions rather than intact material. These impressions are direct evidence of former shell presence and, by extension, former water, even where the shell itself has been removed.

→ Organic staining and peat-like horizons

Organic staining, darkened horizons, or peat-like material indicate stagnant or slow-moving water, waterlogging, or anoxic conditions. These features reflect prolonged saturation rather than brief exposure.

→ Chalk paste, softened chalk, and puttified chalk

Where chalk is logged as paste, soft, weakened, or puttified, this reflects chemical dissolution and mechanical breakdown under sustained saturation. These textures are aqueous in origin and fundamentally different from blocky fracture produced by freeze–thaw.

→ Solution features, voids, and collapse structures

Voids, cavities, and collapse features attributed to solution require long-term water circulation. They indicate groundwater flow paths, dissolution, and structural weakening — processes that cannot occur in dry chalk.

→ Repeated vertical alternation of the above

Perhaps most critically, these features occur repeatedly and at different depths, separated by intact chalk. That vertical stacking is itself evidence of multiple water incursions over time.

What is explicitly excluded

To avoid exaggeration, the following are not counted:

→ drilling-induced fragments or artefacts

→ administrative gaps in logging

→ colour change or staining on its own

→ lithological labels without physical description

→ assumed processes not written in the log

Where an interval is ambiguous, it is excluded.

Additional safeguards

Two further safeguards are applied consistently:

→ Point observations (e.g. “shells noted”) are included in event counts (N) but not inflated in thickness totals (W).

→ Overlapping descriptions at the same depth are treated as a single water occurrence, not multiple events.

These rules are conservative by design. They bias the analysis toward undercounting, not exaggeration.

This matters because every total, percentage, and frequency that follows rests on these fixed definitions. They are stated here in advance and applied uniformly across all 21 boreholes.

What the data show under these constraints, therefore, is not interpretation.

It is arithmetic.

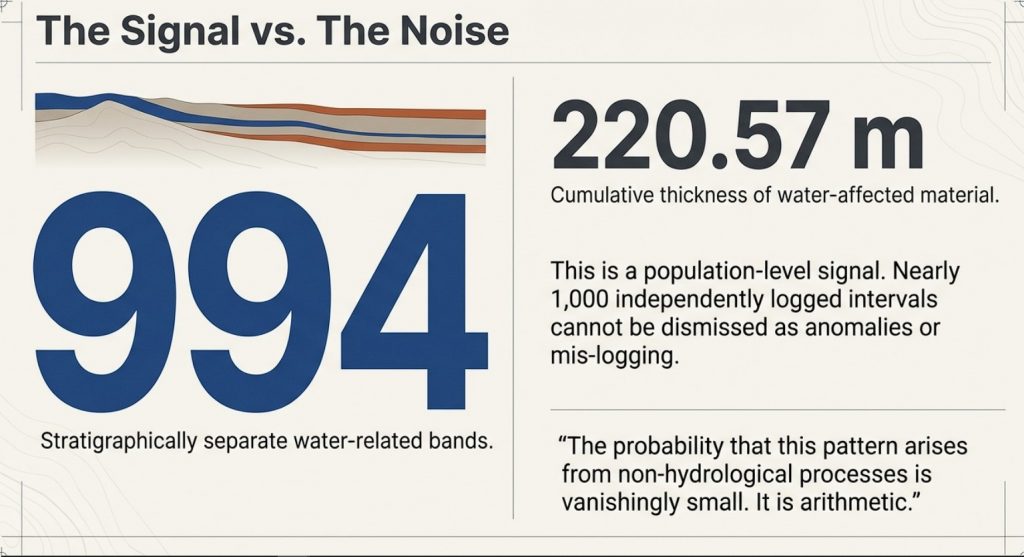

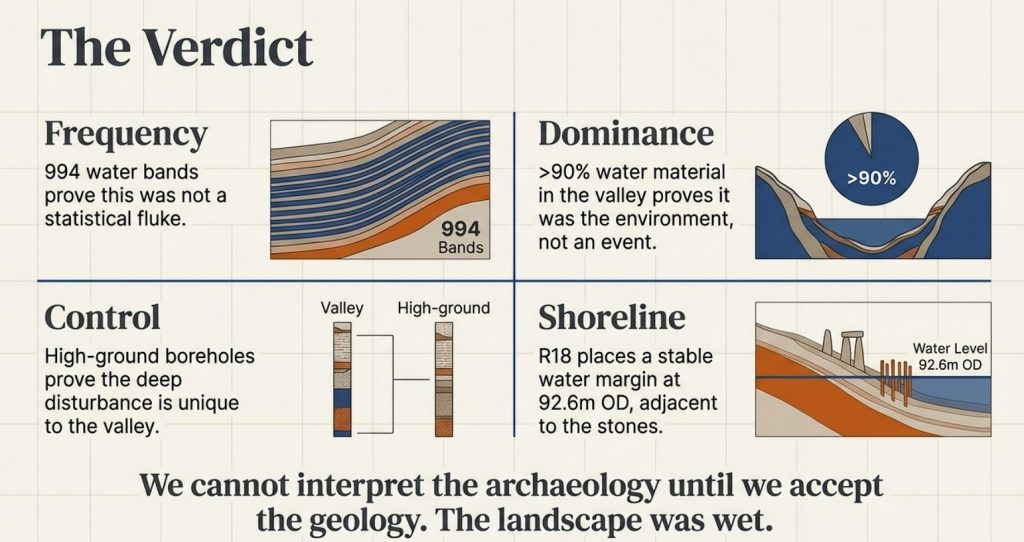

4. The Numbers That Break the Model

Counting replaces interpretation

Once the rules in Section 3 are fixed, the analysis becomes mechanical. There is no scope for reinterpretation, emphasis, or selective description. Each borehole is processed line by line, each qualifying interval counted once, and each thickness measured only where the log permits it.

When this is done across all 21 boreholes surrounding Stonehenge Bottom, the result is unambiguous.

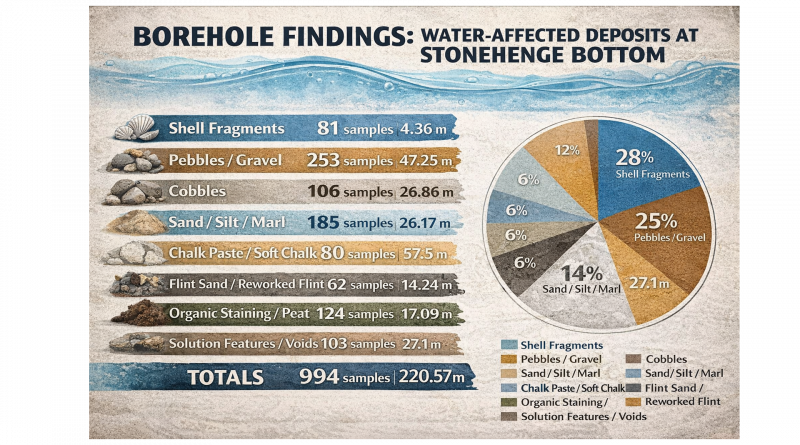

Across the dataset, a total of 994 stratigraphically separate water-related bands are recorded. These bands represent discrete, depth-specific intervals in which water action is explicitly logged. They are not repeated descriptions of the same layer, not interpretive subdivisions, and not inferred events. Each band occupies its own position in the stratigraphic column.

The cumulative thickness of these water-affected intervals is 220.57 metres.

These two figures matter for different reasons:

→ The band count (994) captures frequency: how often water interacted with the subsurface at different times and depths.

→ The cumulative thickness (220.57 m) captures dominance: how much of the valley fill has been shaped by water processes rather than intact chalk.

Together, they describe both repetition and scale.

Distribution by material class

The 994 bands are not confined to a single sediment type. They are distributed across multiple, independent indicators of water action:

→ Shell material and shell-impression horizons

→ Pebble, gravel, and cobble bands

→ Sand, silt, and marl seams

→ Flint lags and reworked flint sands

→ Organic staining and peat-like deposits

→ Chalk paste, softened chalk, and solution zones

→ Voids and collapse features

This diversity matters. A single class could be argued away. A consistent pattern across many classes cannot.

Why this exceeds statistical uncertainty

In subsurface analysis, isolated occurrences can be dismissed as noise. Sparse events can be argued as anomalous. That logic fails completely at this scale.

Nearly one thousand independently logged water-related intervals, stacked vertically through the valley fill, represent a population-level signal. The probability that such a pattern arises from non-hydrological processes — or from mis-logging replicated hundreds of times across different boreholes, contractors, and decades — is vanishingly small.

At this point, the question is no longer whether water was present.

The only remaining questions are how persistent, how extensive, and how it structured the landscape.

What the numbers do not rely on

It is important to be explicit about what these totals are not dependent on:

→ they do not depend on a single “key” borehole

→ they do not rely on shell material alone

→ they are not driven by one sediment class

→ they are not sensitive to minor changes in definition

Even if the most conservative exclusions are applied, the order of magnitude does not change. The signal remains.

This section marks the point where the traditional dry-land model becomes mathematically indefensible. The remaining sections address what these numbers mean spatially, how they vary across the valley, and why they cannot be reproduced on the surrounding uplands.

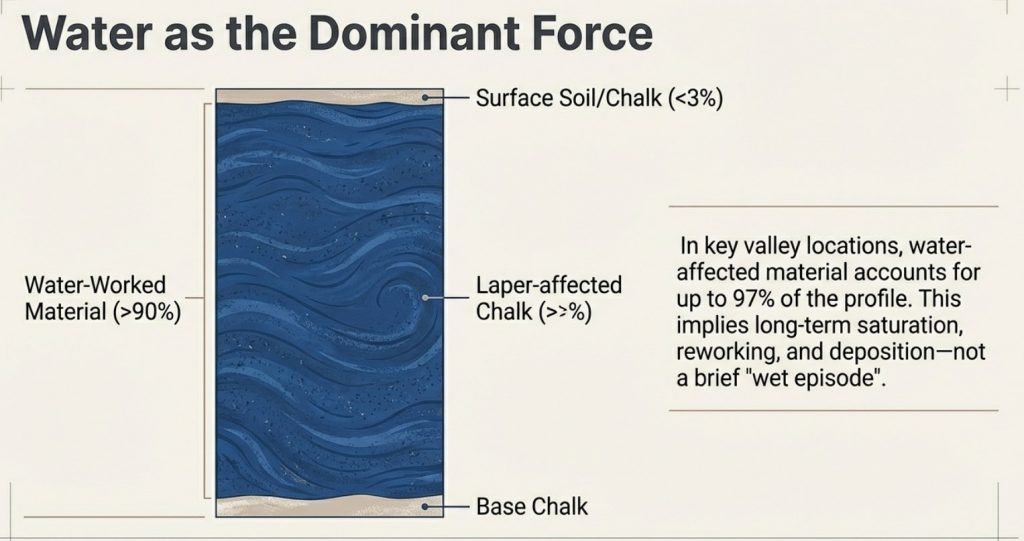

5. Percentage, Not Just Presence

When water controls the subsurface

Counts establish repetition. Percentages establish control.

While the total of 994 water-related bands demonstrates how frequently water interacted with the subsurface, the proportion of each borehole affected shows something more important: whether water was a marginal influence or the dominant process shaping the valley fill.

In several boreholes within Stonehenge Bottom, water-related sediments do not appear as thin, occasional horizons. They make up the majority of the entire borehole profile.

In the most extreme cases, over 90% of the logged sequence, and in at least one borehole, approaching 97%, consists of water-laid or water-altered material.

That figure is not rhetorical. It is arithmetic: the summed thickness of water-affected intervals divided by total borehole depth.

Why percentage matters more than occurrence

A dry chalk landscape affected only incidentally by water would produce a very different subsurface signature:

→ thin, isolated water horizons

→ limited vertical extent

→ low proportional impact

→ intact chalk dominating the sequence

That is not what is observed.

Instead, in key valley-floor locations, intact chalk becomes the minority material, repeatedly interrupted or replaced by gravels, sands, marls, shell-bearing layers, softened chalk, and solution features. Water is not an episode in these boreholes. It is the defining condition.

This distinction is critical. A single water band can be debated. A high band count demonstrates persistence. But when water-related material accounts for nearly the entire stratigraphic record, the environment being recorded cannot reasonably be described as dry.

Why this cannot be dismissed as “local wet spots”

The percentage values are not confined to one anomalous borehole. They recur across multiple boreholes distributed through Stonehenge Bottom, while dropping rapidly toward the valley margins and disappearing entirely on surrounding high ground.

This spatial behaviour matters:

→ dominance in the valley floor

→ reduction upslope

→ absence on the interfluves

That pattern is exactly what a river basin and floodplain system produces. It is not consistent with surface runoff, rainwash, or shallow groundwater effects acting on an otherwise dry landscape.

What high percentages actually record

A borehole composed almost entirely of water-affected material records time, not drama.

It indicates long-term saturation, repeated deposition, reworking, dissolution, and sealing — processes that operate over extended periods. It does not imply catastrophic flooding. It implies a persistent water presence shaping the subsurface continuously.

In that context, the ~97% figure is not an outlier. It is a signal that, in parts of Stonehenge Bottom, the subsurface history is overwhelmingly aqueous.

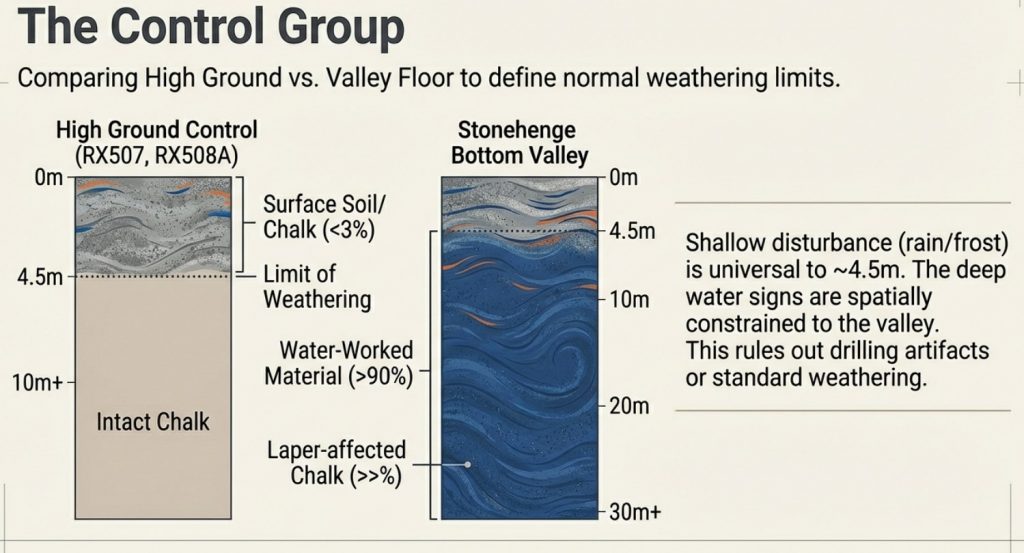

6. Control Boreholes

Defining the maximum depth of non-aqueous disturbance

Any claim that Stonehenge Bottom has been substantially reworked by post-glacial water must first answer a simpler question: how deep does non-aqueous disturbance normally penetrate into chalk on local high ground?

That question cannot be answered with a single borehole.

It requires a control group.

Three boreholes drilled on high ground around Stonehenge provide that control: RX507, RX508A, and RX510A.

These boreholes are located on interfluves outside the Stonehenge valley system, within the same chalk formation, under the same climatic history, and drilled for the same engineering purposes.

What the control boreholes show

Despite differences in total depth and drilling campaign, all three control boreholes record the same outcome:

→ near-surface disturbance confined to approximately 4.0–4.5 m

→ below this depth, structurally intact chalk

→ no progressive softening

→ no stacked gravel horizons

→ no shell material

→ no solution overprint extending downward

This convergence is critical. It shows that shallow disturbance is systematic and limited, not variable or arbitrarily deep.

The depths are consistent:

→ RX507: disturbance to ~4.0 m

→ RX508A: disturbance to ~4.0 m

→ RX510A: disturbance to ~4.5 m

These values define the maximum penetration of periglacial and near-surface processes — rainwash, frost action, soil development, and minor cryogenic disruption — on local high ground.

Why does the drilling method not undermine the control

RX507, RX508A, and RX510A include rotary open-hole drilling, which does not preserve fine sedimentary lamination. No claim is made that these boreholes provide detailed stratigraphic resolution.

Their purpose is different.

Open-hole drilling does not selectively erase:

→ deep gravel or cobble horizons

→ extensive softened or paste-like chalk

→ solution void systems

→ repeated vertical disruption

If such features were present below ~4–5 m, they would still manifest as changes in spoil character and lithological description. Their consistent absence across all three boreholes is therefore meaningful.

Why this recalibration matters

With three independent boreholes showing the same shallow disturbance limit, the analysis elsewhere can be recalibrated correctly:

→ the upper ~4–4.5 m is treated as surface / periglacial noise

→ everything below that depth is evaluated as core chalk behaviour

In the Stonehenge Bottom boreholes, water-related features occur well below this boundary, repeatedly and at multiple depths. That behaviour cannot be attributed to surface processes, periglacial activity, or drilling artefact.

What the control set proves

The control boreholes demonstrate that:

→ deep chalk disruption is not universal

→ it is not inherited from geological time

→ it is not an artefact of logging practice

→ it is spatially constrained to the valley system

Once this control is established, explanations based on dry chalk, preserved periglacial surfaces, or shallow seasonal wetting become untenable.

The contrast is no longer interpretative.

It is geometric and measurable.

Control conclusion

RX507, RX508A, and RX510A together define the maximum depth of non-aqueous disturbance in the Stonehenge landscape.

Everything below that depth in the valley-floor boreholes records a different subsurface regime — one dominated by long-term water interaction.

That control underpins all subsequent sections.

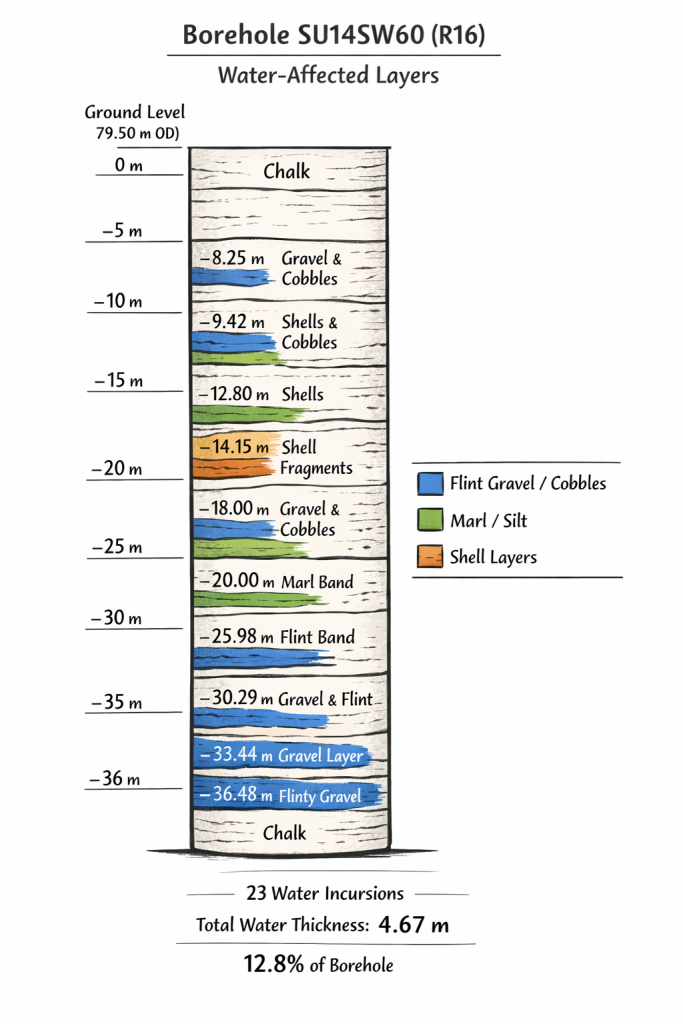

7. Case Study: R16 Counted Properly

From description to arithmetic

To show exactly how the wider dataset was analysed, it is necessary to walk through one borehole in full, line by line, using the fixed rules set out in Section 3. Borehole R16 (SU14SW60) provides a clear example.

R16 is located within the Stonehenge landscape and was logged in detail as part of a British Geological Survey investigation. The borehole has a total depth of 36.57 m and a ground level of 79.50 m OD. No reinterpretation is applied here. Only what is explicitly written in the log is used.

Step 1: Fix the definitions (no flexibility)

A water-related occurrence is counted only where the log records features that require water to exist or to have existed. These include gravel or cobble bands, marl seams, flint lags, shell material or shell impressions, softened or paste-like chalk, and solution-related features.

Colour change alone is excluded. Drilling artefacts are excluded. Ambiguous notes are excluded.

Step 2: Count discrete water occurrences (N)

Working from the top of the borehole to the base, R16 records 23 separate water-related intervals, each at a different depth and separated by non-water intervals.

These are not subdivisions of a single layer. They are discrete stratigraphic horizons, logged independently, and occurring repeatedly through the sequence.

This means water interacted with the subsurface at least 23 separate times at different points in the borehole’s history.

Step 3: Measure total water-affected thickness (W)

Each interval that has a defined thickness is measured and summed. Point observations (such as single shell notes or thin marl seams) are included in the event count but are not inflated in the thickness total.

For R16, the summed thickness of all water-related intervals is:

W = 4.67 m

Out of a total borehole depth of 36.57 m.

Step 4: Convert thickness to percentage

Once thickness is measured, the proportion of the borehole affected by water can be calculated directly:

Water involvement

= 4.67 ÷ 36.57 × 100

= 12.8%

Nearly 13% of the entire subsurface profile shows direct, logged interaction with water.

This figure is not inferred. It is not modelled. It is counted.

Step 5: Calculate frequency (events per metre)

A final metric captures how often water appears through the sequence:

Event density

= 23 events ÷ 36.57 m

= 0.63 water events per metre

In practical terms, R16 records water influence, on average, every 1.6 metres.

That is incompatible with a dry or stable chalk substrate.

8. Case Study: R18 and the Shoreline Signal

Why depth matters more than surface finds

If R16 demonstrates how water repeatedly interacted with the subsurface, R18 (SU14SW62) shows where that interaction stabilised within the landscape. This borehole does not simply record water presence — it records a persistent water level.

R18 is drilled into hard chalk beneath Stonehenge Bottom. As with R16, the analysis relies solely on what is explicitly logged, applying the same fixed rules. What distinguishes R18 is not just the number of water-related intervals, but their vertical organisation.

Within this single borehole, 135 distinct water-related sedimentary levels are recorded, comprising gravels, sands, shell material, organic staining, and solution-related chalk. The cumulative thickness of water-affected material is 9.21 m, representing 18.25% of the borehole.

These figures already place R18 well beyond incidental wetting. But the critical signal lies higher in the sequence.

The erosion boundary and what lies below it

Across multiple boreholes into hard chalk in the Stonehenge area, a consistent pattern emerges: natural surface processes — rainwash, frost action, soil formation, and minor periglacial disturbance — affect only the upper ~3.5 m of chalk. Below that depth, intact chalk is normally expected.

In R18, however, repeated shell-bearing and water-laid sediments occur well below this natural erosion boundary, clustered around approximately 92.6 m OD.

That single fact carries weight.

Below the surface-affected zone, chalk should be structurally intact unless acted upon by sustained subsurface water. Shell material at this depth cannot be explained by surface wash, slope creep, or freeze–thaw processes. Those mechanisms do not transport, preserve, or repeatedly introduce shell-bearing sediments into intact chalk tens of metres below ground.

What is being recorded here is not a transient event, but a stable hydrological condition.

Why this records a shoreline, not a flood

Shells require more than water. They require time, stability, and habitable conditions. A single flood might move gravels. It does not establish repeated shell-bearing horizons at the same elevation.

In R18, water-related sediments recur around a consistent vertical level, indicating that water returned to — or persisted at — approximately the same height over extended periods. That behaviour is characteristic of a shoreline or standing-water margin, not episodic inundation.

This distinction matters. A flood leaves chaos. A shoreline leaves repetition.

Spatial implication: beside the stones, not beneath them

The elevation of the highest repeated water-related horizons in R18 places the shoreline downslope from the later stone circle, in the area now occupied by the former Stonehenge car park and adjacent valley floor. The stones themselves sit slightly above this zone.

This spatial relationship is precisely what would be expected if early activity took place adjacent to persistent water, but deliberately positioned on ground that remained reliably dry.

At this point, the argument is no longer abstract. R18 ties water presence to a specific elevation and location within the landscape.

Why R18 matters beyond itself

R18 does not stand alone. Its shoreline signal aligns with:

→ repeated water dominance shown in the wider borehole matrix

→ high percentage water-affected sequences in nearby valley-floor boreholes

→ the absence of comparable features on surrounding high ground

Together, these strands converge on a single conclusion: Stonehenge Bottom was not merely wet at times. It contained a persistent water margin during the period when the earliest features in the landscape were established.

9. The Mesolithic Posts Reinterpreted

Infrastructure, not ritual

The Mesolithic post holes near Stonehenge have long been treated as anomalous. Dated to around 8300 BCE, they sit uncomfortably outside later monument narratives and are routinely described as symbolic, ritual, or inexplicable precursors to Stonehenge itself.

That framing has always depended on one assumption: that the surrounding landscape was dry.

Once that assumption is removed, the problem disappears.

The spatial problem that ritual never solved

The Mesolithic posts are:

→ located downslope from later monuments

→ positioned several metres above the inferred water level

→ set back from the valley floor

→ aligned along a natural route through the landscape

If these posts were ritual markers, their placement is awkward. They are not centred, not enclosed, and not associated with known ceremonial structures. Their position has always required special pleading.

In a water-dominated landscape, however, their location is exactly where it should be.

Posts above water make sense — posts below it do not

If Stonehenge Bottom contained a persistent water margin during the early Holocene, as the borehole evidence indicates, then the posts occupy a functionally optimal position:

→ safely above sustained water levels

→ close enough for access

→ far enough to avoid saturation

→ visible from the water’s edge

This is not where one places abstract symbols.

It is where one places infrastructure.

What tall timber posts do in watery landscapes

In riverine and floodplain settings, tall timber posts serve well-understood practical roles:

→ mooring points

→ landing markers

→ route indicators

→ boundary and access control

→ stable reference points in shifting terrain

None of these functions requires ceremonial explanation. They require water movement, repeated use, and practical need.

Once water is acknowledged as the dominant landscape factor, the Mesolithic posts cease to be mysterious. They become logical.

Chronology now works instead of fighting itself

The Mesolithic date of the posts is no longer a problem to be explained away. It becomes a key indicator of early engagement with a water-managed landscape.

Long before sarsens or bluestones, the valley was already being structured, navigated, and used. The posts mark activity responding to water, not anticipating monumentality.

In this context, Stonehenge does not begin as a symbolic construction placed into an abstract landscape. It emerges later within a landscape that was already organised around access, movement, and water.

From monument to harbour

This reinterpretation does not diminish Stonehenge. It grounds it.

The earliest activity in the valley is not ritual abstraction imposed on empty land. It is practical engagement with a flooded environment. The Mesolithic posts represent the first fixed points in that system.

Stonehenge, in this light, does not replace a dry ceremonial field.

It formalises a landscape that was already working.

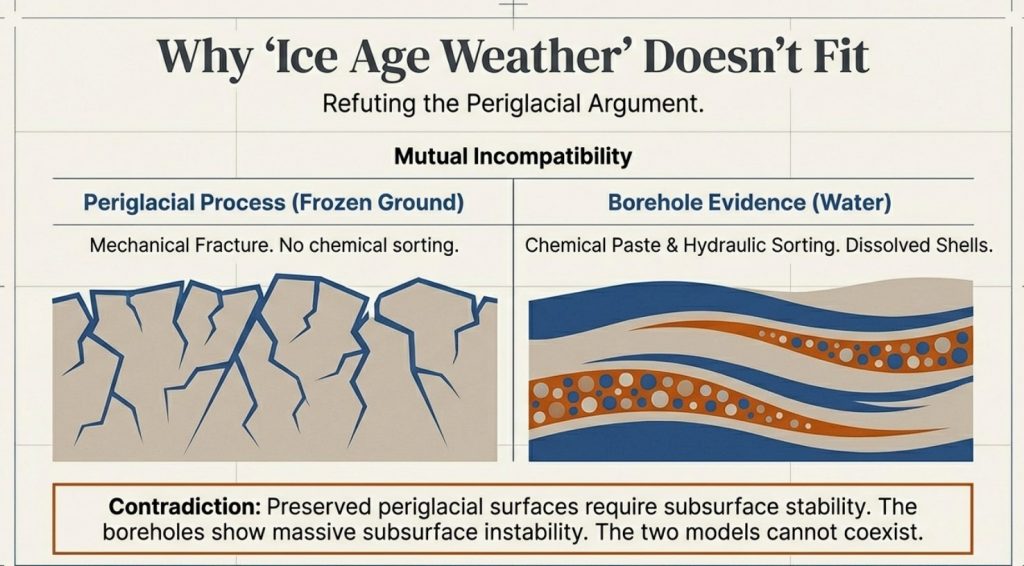

10. The Periglacial Escape Route Fails

Why do the two explanations not coexist

Once extensive post-glacial water activity is demonstrated in the subsurface, a common fallback is to invoke preserved periglacial features at the surface — particularly along the Stonehenge Avenue — as evidence that the landscape must have remained largely untouched since the Late Pleistocene.

This argument fails on first principles.

Periglacial explanations and the documented subsurface record are mutually incompatible. They cannot both be true.

What preserved periglacial features require

For periglacial stripes, polygons, involutions, or solifluction features to survive as recognisable surface relics, several conditions must hold:

→ a relatively stable ground surface since the Late Pleistocene

→ structurally intact chalk beneath the surface

→ dominance of cryogenic fracture rather than chemical solution

→ minimal post-glacial groundwater circulation and reworking

These requirements are well established in periglacial geomorphology. Preservation depends on limited later disturbance, not simply on the prior existence of cold conditions.

What the boreholes actually show

The borehole record beneath Stonehenge Bottom and the Avenue corridor shows a very different subsurface reality:

→ repeated gravel, cobble, sand, and marl bands

→ shell material and shell-impression horizons at multiple depths

→ softened chalk, chalk paste, and solution features

→ voids and collapse structures

→ vertical repetition of water-affected horizons through tens of metres

This is not conjecture. It is logged geological data from multiple independent boreholes.

These features are diagnostic of long-term water circulation, saturation, and reworking. They are not produced by freeze–thaw processes.

Why freeze–thaw cannot explain what is observed

Periglacial processes fracture chalk. They do not:

→ dissolve chalk into paste

→ create solution voids and collapse features

→ repeatedly rework sediments vertically

→ introduce or preserve shell-bearing water horizons

→ generate stacked sequences of hydraulically sorted material

Freeze–thaw acts mechanically and near the surface. The features documented here are chemical, hydraulic, and vertically extensive.

Invoking periglacial processes in this context does not explain the data. It avoids it.

The fatal contradiction

A preserved periglacial surface requires subsurface stability.

The boreholes demonstrate subsurface instability driven by water.

Once chalk has been repeatedly saturated, chemically dissolved, mechanically reworked, and overprinted by groundwater flow, the overlying surface cannot be treated as a pristine Ice-Age relic.

You cannot argue for intact periglacial features resting on a substrate that has been demonstrably broken down by post-glacial hydrology. The two interpretations cannot coexist.

Why surface analogy is no longer sufficient

Periglacial explanations for the Stonehenge Avenue rely almost entirely on surface morphology and analogy with other chalk landscapes. What they do not do is engage with the subsurface evidence directly beneath the features being interpreted.

That omission matters.

In modern geology, subsurface data overrides surface analogy. Where boreholes contradict a surface-based interpretation, the subsurface record must lead.

Here, it does—and it points unequivocally to a landscape that has been substantially reworked since the Ice Age.

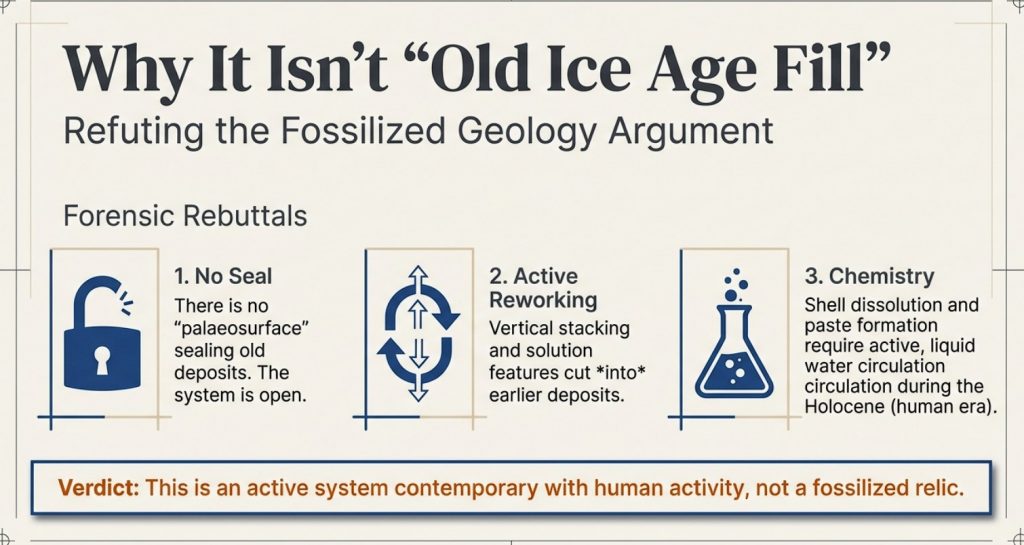

11. Why the “Older Ice Age Valley Fill” Argument Also Fails

Predictions versus what is actually observed

When faced with extensive water-related deposits beneath Stonehenge Bottom, a common fallback explanation is to argue that these features represent an inherited Pleistocene valley fill — formed during an earlier Ice Age, then later frozen, stabilised, and preserved into the Holocene.

At first glance, this sounds plausible.

In practice, it fails every test.

What an inherited Ice Age valley fill would predict

If the Stonehenge valley fill were primarily an older Pleistocene deposit, later left largely undisturbed, the subsurface record should show a consistent set of characteristics:

→ a coherent valley-fill unit with limited internal repetition

→ broad lithological continuity rather than frequent alternation

→ dominance of brecciation and blocky fracture over chemical solution

→ minimal vertical reworking once deposition ceased

→ a sealing palaeosurface separating Ice Age deposits from later soils

In short, the record should show one major depositional phase, followed by stability.

What the boreholes actually show

The borehole data beneath Stonehenge Bottom show the opposite:

→ multiple, discrete water-worked bands stacked vertically

→ repeated alternation between gravels, fines, organic horizons, and chalk

→ solution features cutting earlier deposits

→ shell material introduced at multiple depths, not confined to a single unit

→ no preserved palaeosurface sealing the sequence

This is not the signature of inherited stasis.

It is the signature of repeated reworking.

Why freezing does not preserve this pattern

A frozen or periglacially stabilised valley fill would suppress further vertical reorganisation. It would lock sediments in place, fracture chalk mechanically, and reduce chemical solution.

What is observed instead is:

→ progressive chalk dissolution

→ formation of paste and softened zones

→ collapse and void development

→ repeated sediment input long after initial deposition

These processes require liquid water circulation, not frozen ground.

The shell problem (again)

Shell material is especially diagnostic here.

If the deposits were primarily inherited from an older Ice Age phase, shell-bearing horizons would be expected to occur once, or within a narrow stratigraphic range corresponding to that phase.

Instead, shells and shell-impression horizons recur at multiple depths, often separated by metres of sterile chalk or other deposits.

That pattern requires repeated habitable water conditions, not a single ancient episode.

Why this matters for chronology

An inherited Pleistocene fill would decouple the subsurface record from Holocene landscape use. It would allow water evidence to be dismissed as irrelevant to early Stonehenge.

The borehole data do not allow that move.

The vertical repetition, solution overprinting, and distribution of water-related features demonstrate ongoing Holocene hydrological activity rather than residual Ice Age sediment.

That means the subsurface conditions recorded are contemporary with early human activity in the valley, not a frozen relic beneath it.

The logical endpoint

Once the inherited Ice Age valley-fill model fails, there is no remaining geological mechanism that can explain:

→ hundreds of vertically stacked water-related horizons

→ deep penetration below the periglacial zone

→ dominance of water-affected material in valley-floor boreholes

→ absence of the same features on surrounding high ground

The only explanation that fits all observations is long-term post-glacial water activity confined to the Stonehenge valley system.

At this point, the question is no longer geological.

It is historical.

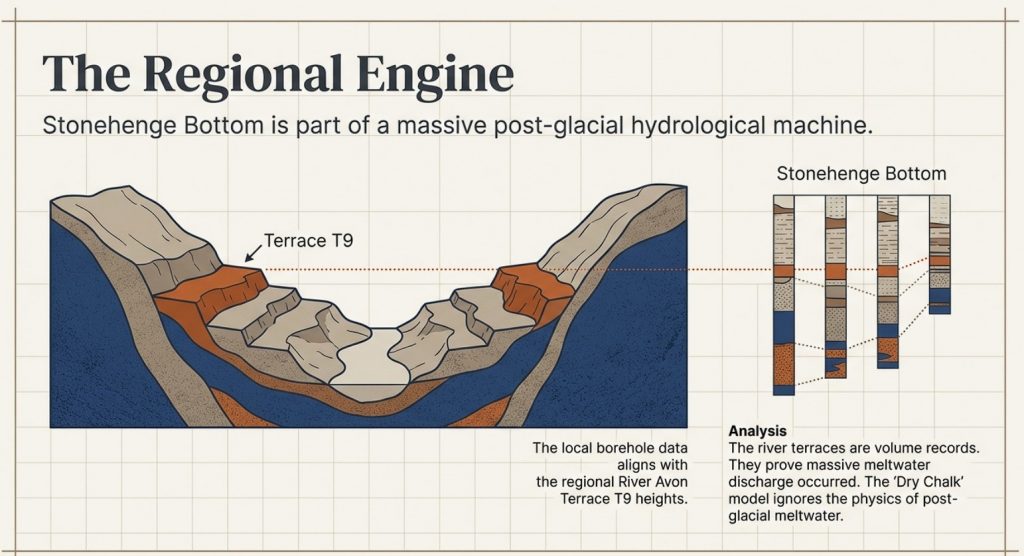

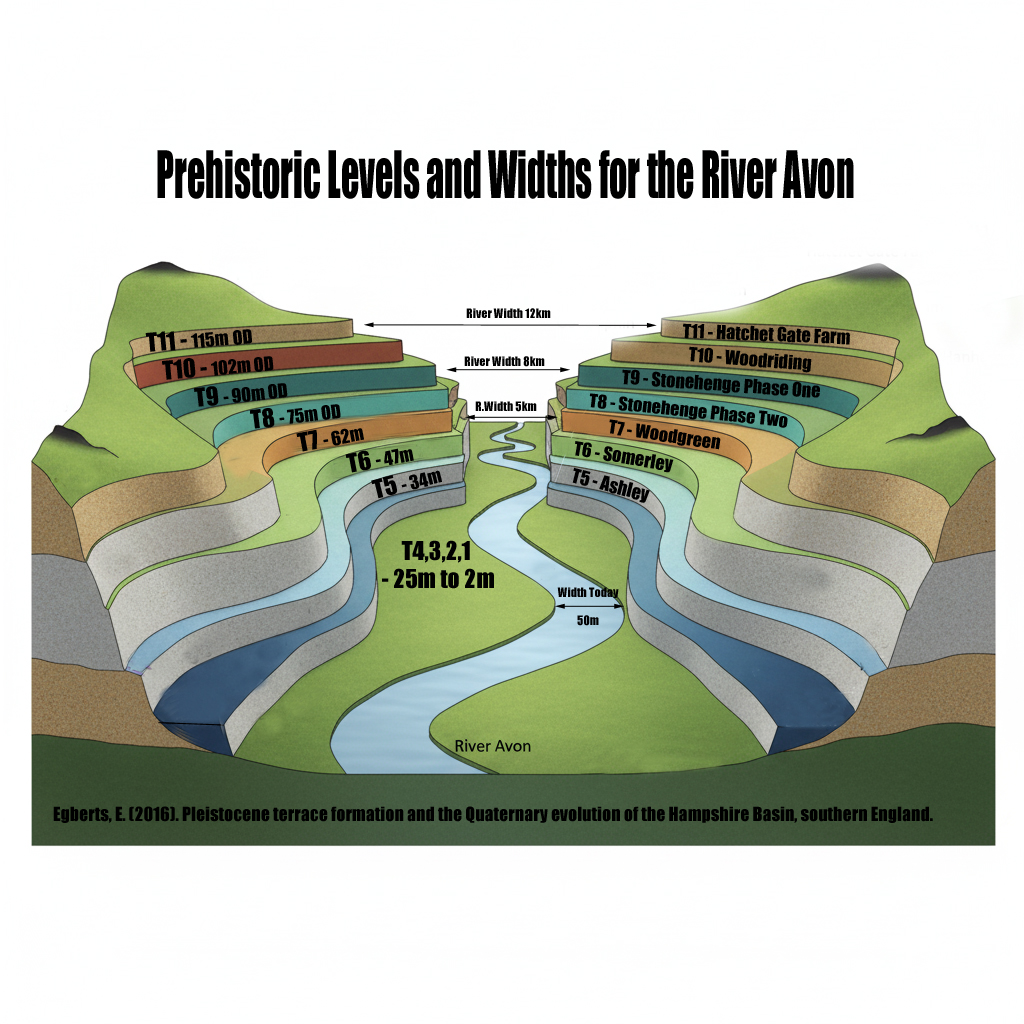

12. Locking into the Wider System

River terraces, meltwater volume, and scale

The borehole evidence beneath Stonehenge Bottom does not exist in isolation. Its significance only becomes fully apparent when it is placed back into the regional post-glacial hydrological system that governed southern Britain after the last Ice Age.

Once this wider context is restored, the Stonehenge record stops looking anomalous and instead becomes inevitable.

River terraces are volume records, not abstractions

River terraces are not symbolic features. They are physical records of water volume, discharge duration, and base-level control.

Each terrace represents a prolonged period during which:

→ meltwater input was sustained

→ base level stabilised long enough for lateral activity

→ rivers occupied a relatively fixed elevation

The Avon terrace staircase is therefore not a static landscape. It is a hydrological archive.

Why terrace height matters more than terrace age

Traditional interpretations tend to treat terraces primarily as chronological markers. In doing so, they obscure their more important function: recording the magnitude of water involved.

Higher terraces require:

→ greater meltwater volumes

→ longer durations of elevated discharge

→ sustained backing-up of inland valleys

This is not controversial. It is basic fluvial physics.

Re-evaluating Ice Age scale

The terrace staircase of the Avon has typically been explained using a model in which the most recent Ice Age contributed only a minor proportion of the total erosive and depositional work — often framed as being small compared to much earlier glacial phases.

The borehole evidence at Stonehenge Bottom contradicts this.

If meltwater volumes from the last glaciation were truly negligible, the valley would not record:

→ repeated Holocene water occupation

→ deep subsurface reworking below the periglacial zone

→ dominance of water-affected material in valley-floor boreholes

The only way to reconcile the terrace staircase with the borehole data is to accept that the most recent Ice Age contributed meltwater volumes large enough to drive active water levels up to at least Terrace T9.

Why Stonehenge Bottom sits where it does

Stonehenge Bottom occupies a low-gradient section of the Avon system, precisely where back-flooding, ponding, and stabilised water levels would be expected during periods of elevated base level.

The borehole record confirms this:

→ water-related horizons stack vertically at consistent elevations

→ disruption intensifies toward the valley floor

→ surrounding high ground remains dry and intact

This is not random. It is system behaviour.

Linking local depth to the regional scale

What the Stonehenge boreholes record is the local expression of a regional process.

The same meltwater that:

→ drove terrace formation downstream

→ sustained discharge into the North Sea

→ reconfigured river systems across southern Britain

…also occupied and re-occupied the Stonehenge valley.

The valley was not an exception.

It was part of the system.

Why this matters for interpretation

Once Stonehenge is placed back into this wider hydrological framework, long-standing interpretive problems dissolve:

→ why early activity clusters near the valley

→ why features sit at specific elevations

→ why subsurface evidence contradicts “dry chalk” assumptions

The landscape was not marginally wet.

It was structurally water-dominated during key periods.

Scale closes the loop.

Small explanations fail because the phenomenon is not small.

A handful of floods cannot produce:

→ hundreds of stratigraphically discrete water horizons

→ deep chalk reworking confined to a valley

→ terrace systems extending across catchments

Only long-duration, large-volume meltwater systems can do that.

Stonehenge Bottom records one node of that system.

And now, for the first time, the subsurface evidence allows that system to be traced — quantitatively, spatially, and historically.

13. What This Forces Archaeology and Geology to Confront

The borehole evidence beneath Stonehenge Bottom does not merely add detail to an existing narrative. It invalidates a foundational assumption shared by both archaeology and geology: that the Stonehenge landscape was fundamentally dry, stable chalk throughout the Holocene.

Once that assumption fails, a cascade of consequences follows.

Archaeology’s problem: interpretation without ground conditions

For decades, archaeological interpretation around Stonehenge has proceeded as if subsurface conditions were either irrelevant or already understood.

They were neither.

Ritual, symbolic, and cosmological explanations were layered onto features whose physical setting had never been tested against the subsurface record. Mesolithic posts became curiosities. Linear features became symbolic avenues. Landscape use was inferred without first establishing whether the ground itself was dry, wet, stable, or seasonally occupied.

The boreholes now show that this approach is untenable.

If water dominated the valley floor for prolonged periods:

→ site placement must be re-evaluated

→ access routes must be reconsidered

→ early structures must be understood as responses to water, not abstractions from it

This is not a reinterpretation of artefacts.

It is a correction to the environmental framework in which they were placed.

Geology’s problem: description without measurement

Geology’s failure is quieter, but deeper.

The borehole logs contained the evidence all along:

→ gravels

→ marls

→ shell material

→ softened chalk

→ solution features

→ voids

But these were described qualitatively, isolated within individual logs, and never synthesised into a landscape-scale analysis.

Words replaced numbers.

Confidence replaced calculation.

No one asked:

→ how many water-related horizons exist

→ how thick they are cumulatively

→ how frequently they occur with depth

→ how they vary spatially across the valley

Once those questions are asked, the “dry chalk” assumption collapses mathematically.

The disciplinary gap that allowed this to persist

Archaeology deferred to geology on ground conditions.

Geology deferred to archaeology on relevance.

Between them, the subsurface record was never integrated.

This is how a landscape can be mischaracterised for decades despite the data being publicly available.

Why this is not an attack on expertise

This work does not argue that archaeologists or geologists were careless or incompetent. It argues something more uncomfortable:

They were working inside inherited models that were never quantitatively tested.

That is not a personal failure.

It is a methodological one.

What changes from here on

The implications are straightforward and unavoidable:

→ subsurface data must precede interpretation

→ water involvement must be quantified, not described

→ control boreholes must be used to define disturbance limits

→ surface features cannot be interpreted independently of what lies beneath them

These are not radical demands.

They are basic scientific ones.

Stonehenge as a test case, not an exception

Stonehenge is not unique because it is famous.

It is unique because it is documented.

If this level of subsurface reworking can be demonstrated here, it raises obvious questions about other chalk landscapes that have never been tested at this resolution.

Stonehenge is simply where the failure becomes visible.

The final position

This work does not ask archaeology or geology to abandon their disciplines.

It asks them to finish the job properly.

The ground has already recorded what happened.

All that remained was to count it.

Because of the huge amount of data and this blog being over 6000 words, PART II, with all the technical data, including all boreholes, will be published next week.

Podcast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unraveling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?