First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification

Contents

- 1 Chapter 1 — The Problem with the Story

- 2 Chapter 2 — What Roman Defensive Ditches Are Supposed to Do

- 3 Chapter 3 — What the Excavations Actually Recorded

- 4 Chapter 4 — The Cross-Sections No One Talks About

- 5 Chapter 5 — LiDAR, Satellite Measurement, and Ground Truth

- 6 Chapter 6 — Why These Ditches Cannot Be Defensive

- 7 Chapter 7 — Water, Industry, and the Infrastructure Everyone Ignored

- 8 Chapter 8 — Why This Was Not a Garrison, but a Controlled Production Site

- 9 Chapter 9 — Why Roads Fail, and Rivers Don’t

- 10 Chapter 10 — When Assumption Replaces Science

- 11 Case Study: Testing the “Roman Road” Claim Against the Ground

- 12 Smoking Gun: The Priests Bank Junction and the End of Cam High Road

- 13 Podcast

- 14 Author’s Biography

- 15 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 16 Further Reading

- 17 Other Blogs

Chapter 1 — The Problem with the Story

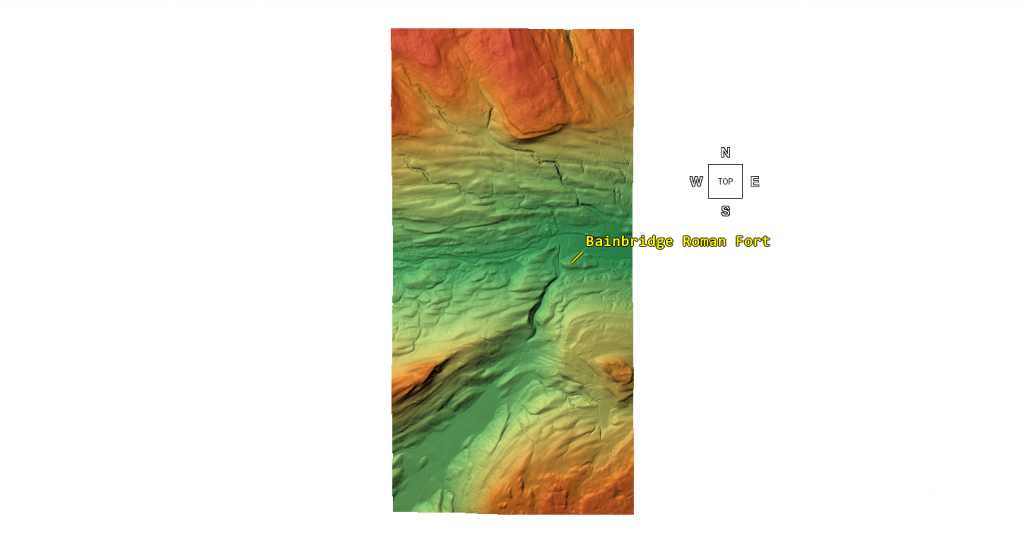

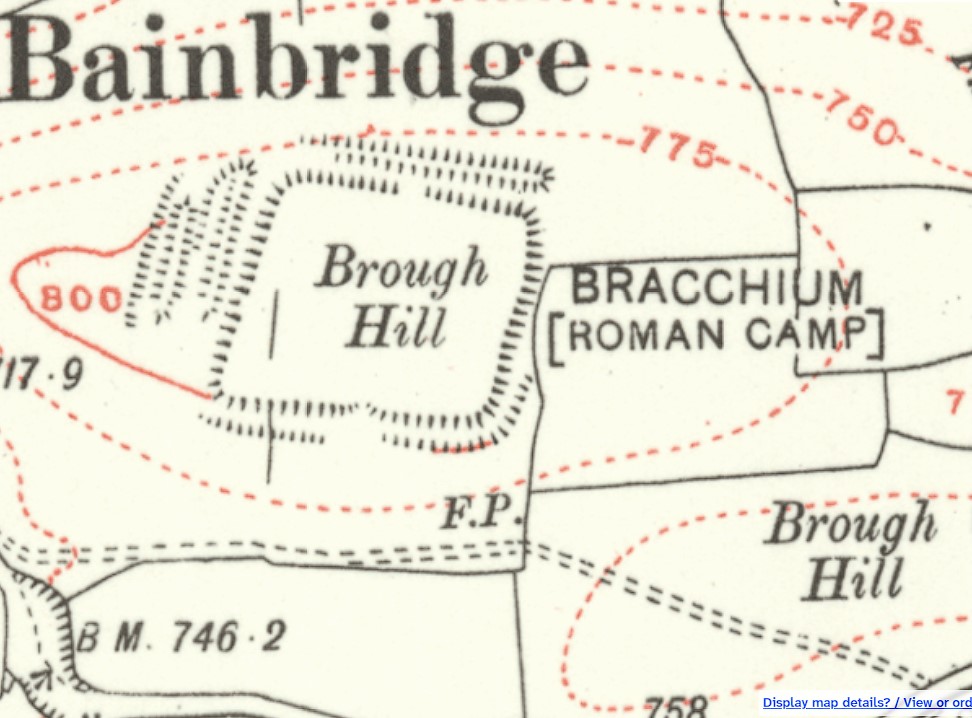

Bainbridge, known in the Roman period as Virosidum, is almost universally described as a standard Roman auxiliary fort. The explanation usually follows a familiar pattern: the fort controlled movement through Wensleydale, was supplied by Roman roads, and functioned as a military garrison in an otherwise quiet upland landscape. This narrative appears in guidebooks, gazetteers, official records, and popular archaeology alike. It is repeated so often that it has become a fact. (Bainbridge Roman Fort)

But repetition is not evidence.

The central problem with the Bainbridge story is not that it is impossible, but that it has rarely been tested against the physical landscape. Interpretation has tended to move in one direction only. Once Roman occupation is identified, roads are assumed, defences are supposed to behave conventionally, and surrounding earthworks are absorbed into a military narrative whether or not their form, scale, or placement actually supports that role. The questions that should come first — what the terrain shows, what was excavated, and what functions the measured features support — have largely been left unasked.

This matters because Roman military installations were not symbolic structures. They were functional systems, engineered to solve specific problems: defence, logistics, production, and control. Roman ditches, ramparts, roads, and drains were designed according to purpose, not tradition. If a feature cannot plausibly perform its supposed function when examined geometrically and physically, then the interpretation attached to it deserves re-examination, regardless of how long it has been accepted.

Recent decades have provided archaeology with a powerful corrective tool: high-resolution LiDAR, combined with satellite measurement and improved landscape modelling. These technologies allow entire sites to be examined without the distortion introduced by vegetation, later land use, or selective trenching. When excavation records are re-examined alongside these datasets, interpretation can finally be tested against scale, depth, and behaviour, rather than inferred from labels.

At Bainbridge, this immediately creates tension. The site is isolated. It does not clearly defend a town, a frontier, a pass, or a demonstrable engineered route. The surrounding earthworks do not behave like textbook Roman military defences when measured. And perhaps most significantly, the excavation evidence from within the site points not to a quiet garrison but to organised, specialist industrial activity, including ironworking, copper-alloy casting, and silver assaying.

These are not marginal details. They go to the heart of what the site was for.

There is also a deeper assumption that requires scrutiny: the idea that Roman-period occupation automatically implies Roman origin. Across Britain, Roman forts, temples, and administrative buildings frequently sit on earlier places of importance. The presence of a Roman temple at Maiden Castle, for example, does not make the hillfort Roman in origin; it demonstrates Roman reuse of an existing landscape. Roman material culture has a habit of dominating interpretation once it appears, pulling earlier phases into its orbit even when the evidence does not demand it.

The excavation reports at Bainbridge do not rule out earlier activity, nor do they claim that the site was founded on a blank landscape. They record complexity, phased development, and features whose function is not fully resolved. What has tended to happen since is that Roman occupation has been allowed to define the entire story, rather than being treated as one phase within a longer sequence.

This blog does not claim that Bainbridge must be pre-Roman. It makes a more cautious and defensible point: Roman presence does not, by itself, explain why this place mattered. Given the site’s hydrological position, landscape-scale earthworks, and industrial function, it is entirely plausible that the Romans formalised, enclosed, and secured a place that already had economic or strategic significance.

That distinction matters. It changes the central question from “why did the Romans build a fort here?” to “why was this place important long before a fort existed?”

What follows is not speculation, but a step-by-step examination of excavation data, ditch geometry, LiDAR profiles, satellite measurements accurate to within half a metre, and basic principles of Roman engineering. When these strands are allowed to speak together, the traditional garrison-fort narrative begins to fail — not dramatically, but decisively.

The landscape has been telling us a different story all along.

We are finally in a position to listen.

Chapter 2 — What Roman Defensive Ditches Are Supposed to Do

Roman military engineering was not symbolic, stylistic, or vague. It was functional, standardised, and purpose-built. Every component of a Roman fort — ramparts, ditches, gates, roads, drains — existed to solve a clearly defined problem. If a feature does not perform its supposed function when examined physically, then its interpretation deserves scrutiny, regardless of how often it has been repeated in the literature.

The defensive ditch (fossa) is a good place to start, because its purpose is unambiguous. A Roman defensive ditch is not merely a boundary marker; it is an active obstacle designed to slow, destabilise, injure, and expose attackers to missile fire from the rampart. This function dictates its geometry.

Across Roman Britain, the defensive ditch typically exhibits three consistent characteristics:

First, depth. A functional Roman leg-breaker ditch is usually between 1.8 and 3.0 metres deep. Depth matters more than width. A shallow ditch may inconvenience movement, but it does not seriously impede a determined attacker. Roman engineers understood this perfectly.

Second, profile. Defensive ditches are usually steep-sided and V-shaped, sometimes with an additional ankle-breaker slot or drainage channel cut into the base. The steep sides make footing difficult, while the narrow base concentrates weight and increases the risk of injury. These profiles are hostile by design.

Third, placement. Roman defensive ditches sit immediately in front of ramparts, creating a combined system: ditch, rampart, and palisade or wall working together. The ditch is not an isolated feature; it is part of an integrated defensive machine.

When these conditions are met, the ditch works. When they are not, it doesn’t.

Importantly, Roman engineers did not waste labour. Digging earth was expensive in terms of human resources, and unnecessary excavation was avoided. A ditch that is wide but shallow, gently sloped, or easily crossed represents poor return on effort if its purpose is defence. Such features may look impressive on a plan, but they do not function as military obstacles.

This distinction is critical because archaeological descriptions often rely on shorthand. A ditch may be described as “V-shaped” in text, but without reference to depth, angle, or context, that label alone tells us very little about function. A shallow V-shaped channel can serve drainage just as easily as defence — sometimes more so.

Roman sites also contain many ditches that are not defensive at all: drains, construction cuttings, boundary markers, water-management features, industrial channels, and temporary works. These are frequently narrower, shallower, and more responsive to local topography than true defensive fossae. Function cannot be inferred from shape alone.

This is why geometry matters. Width, depth, slope angle, placement, and relationship to other features determine what a ditch does, not what it is called. Any interpretation that ignores these variables in favour of typological labels is vulnerable to error.

The purpose of this chapter is not to deny the existence of Roman defensive ditches — they are well documented and unmistakable when present. It is to establish a clear, testable baseline: if a ditch cannot plausibly function as a defensive obstacle, then it should not be interpreted as one without further evidence.

With that baseline in place, we can now return to Bainbridge and ask a simple, unavoidable question: do the ditches recorded there behave like Roman military defences — or do they act like something else entirely?

Chapter 3 — What the Excavations Actually Recorded

Any serious reassessment of Bainbridge must begin with the excavation record, not with later summaries, gazetteers, or interpretive maps. The primary excavations at Bainbridge — carried out by Collingwood, Wade, and later synthesised by Hartley — were careful, methodical, and largely limited in scope. They did not attempt a landscape-scale investigation. What they recorded, and what they did not, matters.

One of the most important points to establish immediately is that the excavators did not describe a single, uniform defensive system. Instead, they recorded ditches of different types in different positions, with markedly different dimensions and characteristics. Later interpretations have tended to collapse these distinctions into a single “Roman defensive ditch” narrative, but the original data does not support that simplification.

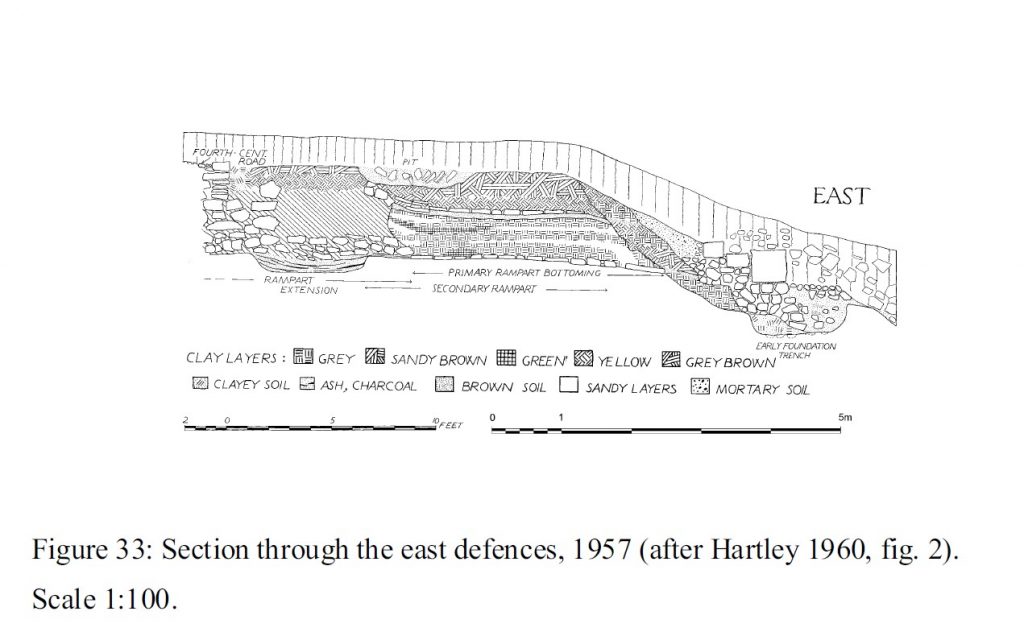

The excavations clearly identify an inner ditch, closely associated with the rampart. This ditch conforms broadly to expectations for Roman military engineering. It is relatively narrow, steep-sided, and, in places, V-shaped, sometimes with a square-cut drainage slot at the base. Its depth is significantly greater than the outer features, and its position immediately in front of the rampart makes defensive sense. There is no controversy here: this inner ditch behaves like a Roman military fossa.

However, beyond this inner ditch, the excavators encountered additional outer ditches, particularly on the western side of the site. These are the features that matter for the present discussion—and they are fundamentally different.

The published reports describe these outer ditches as broad and shallow, with recorded depths typically ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 metres. Widths are substantially greater than those of the inner ditch, reaching up to roughly 8 metres in some excavated sections. Spoil from these cuts was often thrown outward to form low, wide scarps, rather than steep rampart faces. These are not incidental details; they define how the features function.

Crucially, the excavators themselves note that these outer ditches were relatively short-lived, often deliberately backfilled rather than allowed to silt naturally. This behaviour is difficult to reconcile with long-term defensive use, but entirely consistent with features that were functional, temporary, or periodically reconfigured.

Although some of these outer ditches are described in the text using shorthand terms such as “V-shaped”, the accompanying measurements and section drawings tell a more nuanced story. A shallow cut with gently sloping sides can technically be V-shaped without functioning as a leg-breaker. Geometry, not vocabulary, determines function.

It is also important to note what the excavations did not do. They did not systematically section the broader landscape features now visible on LiDAR. They did not attempt to trace these ditches beyond the immediate vicinity of the fort. They did not integrate hydrology, slope behaviour, or wider landscape management into their interpretation. These omissions are understandable given the period in which the excavations were conducted, but they limit what can legitimately be concluded.

What the excavation record therefore gives us is not a simple answer, but a set of constraints. It shows that Bainbridge had at least one conventional Roman defensive ditch near the rampart. It also shows that it possessed additional, much broader and shallower ditches whose form, depth, and treatment differ markedly from standard military defences.

The mistake comes later, when these distinct features are treated as if they belong to a single defensive logic. Once the inner and outer ditches are merged, the site can be described as a typical fort with unusually large defences. But when they are kept separate — as the excavators themselves recorded them — a different picture begins to emerge.

The excavation evidence does not demand that all ditches at Bainbridge were defensive. On the contrary, it quietly suggests that they were not all doing the same job.

With this distinction firmly in place, we can now turn to the critical question that follows naturally from the data: if the outer ditches were not functioning as leg-breaker defences, what were they actually for?

That question leads directly to the cross-sections—and to the point where the traditional narrative begins to fail.

Chapter 4 — The Cross-Sections No One Talks About

Archaeological interpretation often leans heavily on labels: “defensive ditch”, “V-shaped”, “Roman military”. But labels only have meaning if the geometry behind them actually works. At Bainbridge, the cross-sections recorded during excavation — and now independently confirmed through LiDAR and satellite measurement — quietly undermine the defensive interpretation that has been attached to the outer ditches for decades.

The critical issue is not whether a ditch can be described as “V-shaped” in plan or section. The question is whether that ditch can function as a Roman military obstacle. When the excavated cross-sections of the outer ditches are adequately examined, the answer is clear: they cannot.

The excavated outer ditches at Bainbridge are consistently recorded as very shallow, typically in the range of 0.4 to 1.0 metres deep, and relatively broad, with widths approaching 8 metres. The section drawings show gently sloping sides and a flattened or rounded base. Even where the profile converges toward a point, the angles are shallow, and the overall depth is minimal. This is not a leg-breaker. It is not even close.

A Roman defensive ditch is designed to destabilise, injure, and delay an attacker. A ditch less than a metre deep fails all three tests. An adult can step into and out of it with little loss of balance. A group can cross it rapidly. There is no meaningful exposure time beneath the rampart, and no realistic risk of injury. Calling such a feature “defensive” relies entirely on terminology, not on function.

Depth is decisive here. Roman engineers did not rely solely on width. A wide but shallow ditch is inefficient: it requires substantial labour to excavate but delivers little defensive benefit. Roman military practice favoured depth and steepness, not broad shallow cuts. This is why classic Roman fossae are narrow, steep, and often augmented with ankle-breaker slots. The Bainbridge outer ditches exhibit none of these characteristics.

Context makes the defensive interpretation even weaker. Some of these shallow ditches lie inside the broader defensive system, not immediately in front of the rampart where a leg-breaker would be effective. A shallow obstacle placed internally makes no military sense at all. You do not defend a fort by creating trip hazards within your own circulation space, particularly in a site that shows long-term occupation, movement of materials, and industrial activity.

Once defence is removed from the equation, the geometry starts to make sense. Shallow, broad ditches are extremely effective for water management. They collect runoff from ramparts and slopes, control drainage across the site, and prevent waterlogging of working areas. In an industrial context — especially one involving metalworking — this is not incidental infrastructure. It is essential.

The excavation reports themselves hint at this functional reality, even if they stop short of stating it explicitly. The outer ditches are described as short-lived, deliberately backfilled, and lacking evidence of long-term silting. These are not the characteristics of permanent military defences. They are the characteristics of managed features, which are altered or replaced as needs change.

When these cross-sections are compared with modern LiDAR profiles and satellite measurements — accurate to within approximately ±0.5 metres — the match is striking. The shallow depths and broad profiles seen in excavation align closely with what is visible across the wider landscape today. There is no contradiction between excavation and remote sensing. The contradiction lies between the data and the interpretation.

This is the point at which the traditional narrative breaks. A ditch that cannot function as a defensive obstacle should not be interpreted as one simply because a fort exists nearby. Geometry does not lie, and physics does not bend to narrative convenience.

The cross-sections at Bainbridge do not describe a fortress bristling with hostile obstacles. They describe a site where water, movement, and activity were being managed, not where attackers were being repelled.

Once this is recognised, the question is no longer “why are these defences so odd?”

It becomes “why was water management so important here?”

And that question leads directly to industry.

Chapter 5 — LiDAR, Satellite Measurement, and Ground Truth

One of the strengths of modern archaeology is that excavation no longer stands alone. Features recorded decades ago in narrow trenches can now be tested against whole-landscape datasets that reveal form, scale, and context with far greater clarity. At Bainbridge, high-resolution LiDAR and satellite measurements do not contradict the excavation evidence—they confirm it and, in doing so, expose the weakness of the traditional interpretation.

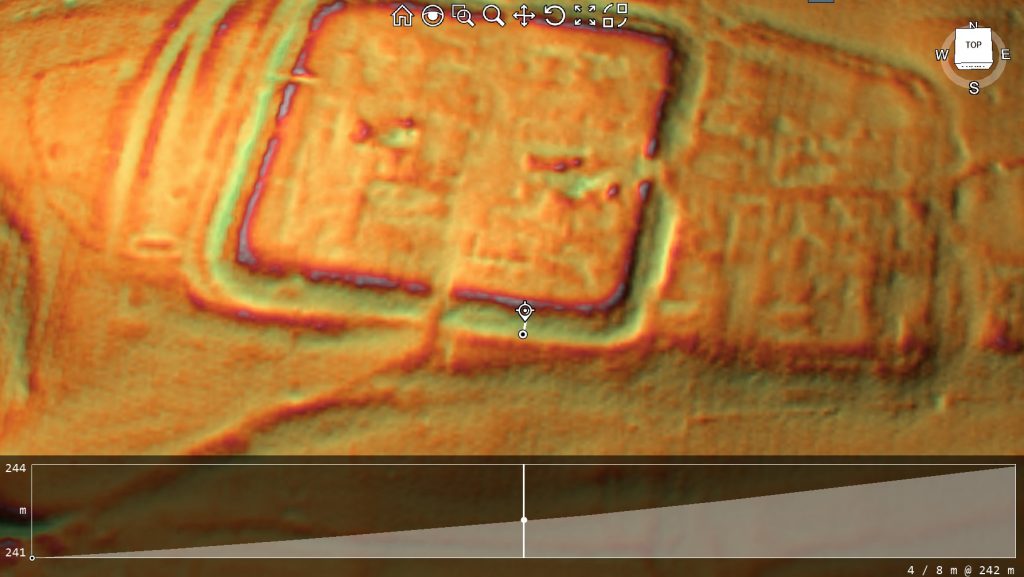

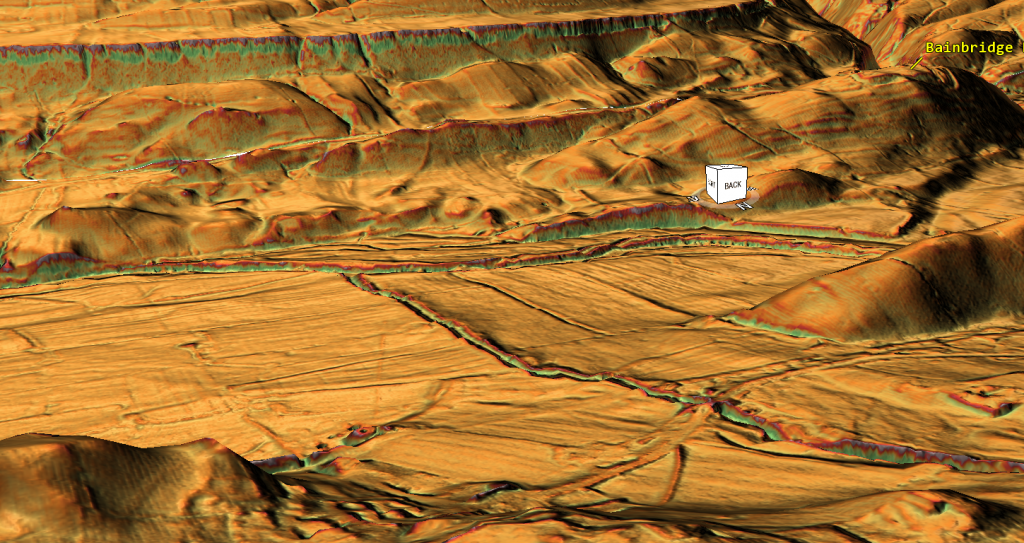

LiDAR has a particular advantage in that it removes vegetation and modern land use from the equation. When examined using multiple hillshades, colour relief, and oblique or horizontal views, features that are genuinely engineered behave very differently from those produced by drainage, erosion, or long-term landscape management. Roman military works, when present, tend to stand out clearly: aggers persist, ditch lines remain crisp, and geometry resists topography. At Bainbridge, that behaviour is notably absent outside the inner defensive zone.

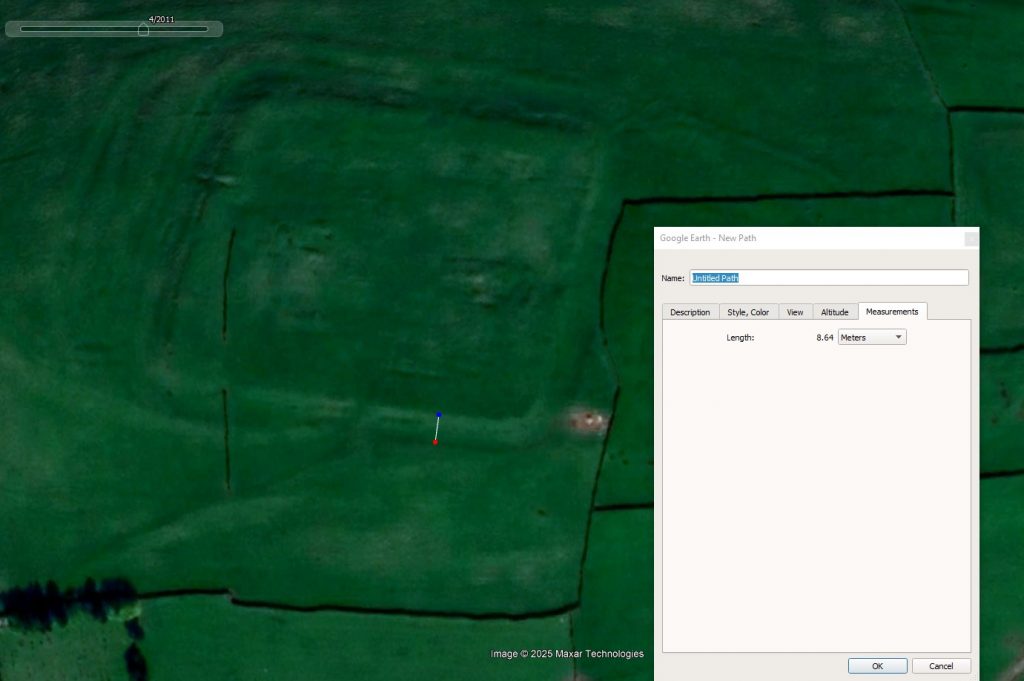

Using LiDAR profiles and Google Earth measurement tools, the principal outer ditch surrounding the site can now be measured with reasonable confidence. Across multiple transects, the ditch consistently falls within a width range of approximately 8.0–8.6 metres, with measurement accuracy to around ±0.5 metres. This result is not derived from a single section or favourable angle; it repeats across the landscape wherever the feature is visible.

Just as important as width is profile. The LiDAR cross-sections show a broad, shallow cut with gently sloping sides and no sharply incised base. There is no indication of a steep V-profile, no ankle-breaker slot, and no abrupt edge that would signal a deliberately hostile obstacle. Instead, the ditch blends smoothly into the surrounding slope, exactly as described in the excavation sections of the outer ditches.

This correspondence matters. It means the excavated sections were not anomalies or local quirks; they were representative of a much larger, coherent landscape feature. LiDAR does not reveal a hidden deeper ditch waiting to be found. It reveals continuity—the same shallow geometry repeated beyond the excavation trenches.

Equally telling is what LiDAR does not show. There is no evidence of large-scale rampart construction associated with these broad ditches. There is no agger-like build-up of material, no sharp counterscarp, and no consistent defensive frontage. The spoil appears dispersed or levelled rather than piled into a formidable barrier. This is consistent with features designed to manage space or water, not to resist assault.

Satellite imagery reinforces the same picture. Measurements taken independently of LiDAR produce comparable widths and confirm that the feature is not the result of modern agricultural activity or mapping artefact. The ditch respects natural slope and drainage patterns rather than imposing a rigid, engineered geometry across them. That behaviour is fundamentally non-military.

What is especially significant is that these measurements now remove uncertainty. Debate no longer hinges on impressionistic descriptions such as “large” or “substantial”. We are dealing with quantified geometry. An outer ditch approximately 8–8.6 metres wide and less than a metre deep simply does not behave like a Roman defensive work, regardless of how it has been labelled in the past.

This also resolves a long-standing interpretive tension. Excavation reports described shallow, broad ditches that did not sit comfortably within a defensive model, while later summaries continued to treat them as such. LiDAR bridges that gap by showing that the excavators were accurately recording the feature—and that the problem lies in how those records were later interpreted.

At this point, the question shifts again. If excavation sections and modern landscape data tell the same story, and that story is incompatible with defence, then the interpretation must change. The outer ditches at Bainbridge were doing something, but that something was not stopping attackers.

Measured against the ground itself, the evidence is no longer ambiguous.

The outer ditches are real, coherent, and deliberate — but they are not military defences.

Understanding what they were for requires us to stop thinking like soldiers and start thinking like engineers.

Chapter 6 — Why These Ditches Cannot Be Defensive

By the time geometry, depth, and landscape context are considered together, the defensive interpretation of Bainbridge’s outer ditches becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. This is not a matter of alternative opinion; it is a matter of function. A feature that cannot physically perform the task assigned to it should not continue to be interpreted as if it does.

A Roman defensive ditch works because it creates risk and delay. Its purpose is to force attackers to descend into a confined space, lose balance, and expose themselves to missiles while struggling to climb out. This requires depth, steep sides, and placement directly in front of a rampart. A ditch that is shallow, broad, and gently sloped fails on every count.

At Bainbridge, the outer ditches are consistently less than a metre deep. Even allowing for erosion, backfilling, or truncation, their present profiles do not approach the depth required for a leg-breaker. An able-bodied adult can step into and out of such a ditch with little difficulty. Groups could cross it rapidly, carts could be manhandled across it, and animals would not be seriously impeded. As a military obstacle, it is ineffective.

Placement further weakens the defensive argument. Some of these ditches lie well beyond the immediate rampart zone, while others sit in positions that would place them inside the broader circulation space of the site. Roman forts were busy environments. Soldiers, pack animals, carts, and supplies moved constantly. Introducing shallow obstacles within or immediately adjacent to internal working areas would hinder daily operation far more than it would hinder an attacker. Roman military design avoids this.

The labour logic is also wrong for defence. Digging an eight-metre-wide ditch requires significant effort. Roman engineers did not expend manpower on features that offered poor defensive return. If defence were the aim, the same labour could have produced a far deeper, steeper, and more effective obstacle. The fact that it did not strongly suggests that defence was not the priority.

Once the defensive explanation is removed, the geometry starts to make sense in a different way. Broad, shallow ditches are highly effective at controlling water. They intercept runoff from ramparts and slopes, channel excess water away from working areas, and reduce erosion. In valley-side locations like Bainbridge, managing water is not optional — it is essential to keeping a site functional.

This is particularly relevant given what the excavations reveal about activity within the site. Metalworking requires water at multiple stages: cooling and quenching hot metal, washing ores, managing ash and waste, and preventing working surfaces from becoming waterlogged. Shallow, wide ditches allow water to move predictably and safely through a site without cutting deep scars or destabilising structures.

The excavation reports themselves support this functional reading, even if they stop short of stating it outright. The outer ditches are described as short-lived, deliberately backfilled, and frequently reworked. Defensive ditches are normally maintained; water-management features are altered as needs change. The behaviour recorded in the ground fits the latter pattern far better than the former.

There is also a conceptual issue at play. Archaeology has a tendency to treat all ditches associated with a fort as “defensive” by default. Yet Roman sites are full of non-defensive cut features that serve practical purposes. Drainage, construction, zoning, and industrial processes all generate ditches that can superficially resemble defences when stripped of context.

At Bainbridge, the evidence points consistently in one direction. The outer ditches lack the depth, profile, placement, and permanence required for military defence. They possess exactly the characteristics expected of managed infrastructure in a working, industrially active site.

If these ditches were not built to stop enemies, then the key question changes again. It is no longer “why is this fort so strangely defended?”

It becomes “why was water management so critical to the operation of this site?”

Answering that question takes us directly to industry.

Chapter 7 — Water, Industry, and the Infrastructure Everyone Ignored

Once the defensive interpretation of the outer ditches is set aside, the question is no longer why Bainbridge’s defences look wrong, but why water management appears to have been such a priority. At this point, the excavation evidence and the landscape data begin to reinforce one another in a way that is difficult to ignore.

Bainbridge sits on a valley-side position above the River Bain, close to its confluence with the Ure. This is a hydrologically active setting. Runoff from higher ground, seasonal saturation, and fluctuating water tables would all have affected the site. Any long-term occupation here — military or otherwise — would have required deliberate control of surface and subsurface water.

The geometry of the outer ditches fits this requirement precisely. Broad, shallow channels are highly effective at intercepting runoff, slowing flow, and directing water away from key working areas without destabilising buildings or ramparts. Their gentle slopes reduce erosion, while their width allows them to function even during periods of heavy rainfall. This is infrastructure designed for management, not obstruction.

This matters because Bainbridge was not a quiet administrative outpost. The excavations demonstrate repeated and sustained industrial activity within the site, including iron smithing, copper-alloy casting, and silver assaying. These are water-dependent processes. Metalworking generates heat, waste, slag, ash, and residues that must be cooled, quenched, washed, and removed. Without reliable drainage, such activity quickly becomes impractical.

In this context, water is not an afterthought — it is a requirement. Controlled drainage protects furnaces and working floors, prevents contamination of materials, and allows waste to be managed rather than dispersed randomly across the site. Shallow ditches that can be altered, backfilled, or re-cut as production needs change are exactly what one would expect in a working industrial environment.

The excavation reports quietly support this interpretation. The outer ditches are repeatedly described as short-lived and deliberately backfilled. This behaviour makes little sense for defensive features, which are normally maintained and periodically re-cut. It makes perfect sense for functional infrastructure that is modified as layouts change, activities expand or contract, or new working zones are established.

The presence of coal as a fuel source strengthens this picture further. Coal use implies sustained, high-temperature operations rather than occasional repair work. It also implies smoke, waste, and heat management challenges — all of which benefit from controlled airflow and drainage. Water management and industrial activity are inseparable in such settings.

Seen in this light, the outer ditches are not anomalous at all. They are part of a managed operational landscape, designed to keep a busy, productive site functioning over a long period. Their scale reflects the scale of activity, not the scale of threat.

This also explains why these features do not conform to textbook Roman military design. They were not built to meet a standard defensive template; they were built to meet local, practical needs. Roman engineers were pragmatic. They adapted form to function, especially in economically important sites.

Once water management is recognised as a central concern, Bainbridge stops looking like a strangely defended fort and starts looking like a place of work — a site where control, organisation, and infrastructure mattered more than spectacle.

And that leads directly to the next question: if Bainbridge was an industrial site first and a military site second, what was the military actually there to do?

That question takes us straight to security, control, and the real role of the garrison.

Chapter 8 — Why This Was Not a Garrison, but a Controlled Production Site

Chapter 8 – The Metalworking Evidence and the Question of Origin

One of the strongest pieces of evidence at Bainbridge has always been the scale and diversity of metalworking debris recovered during excavation. This includes ironworking waste, copper-alloy residues, silver-processing material, coal, and lead-based by-products. Such an assemblage immediately distinguishes the site from a routine military garrison, where limited repair and small-scale production would normally be expected. Instead, the material points to sustained industrial activity.

The published analysis usefully presents the metalworking debris by chronological phase, expressed by weight. When examined closely, however, this distribution raises a critical question that has not been fully explored in previous interpretations.

Of the total metalworking assemblage, approximately 79% is recorded as “unphased” — meaning it cannot be securely attributed to Roman stratigraphic contexts. Only around 21% of the material can be confidently assigned to Roman-period phases. This imbalance is not a minor statistical detail; it is the dominant signal in the dataset.

Importantly, “unphased” does not mean “Roman by default.” It indicates that the material lies outside tightly controlled Roman horizons, either because it predates the fort, postdates it, or derives from long-lived or repeatedly disturbed industrial deposits. In a site where metalworking was primarily driven by a Roman garrison, we would expect the opposite pattern: strong clustering within Roman phases, clear association with military structures, and a comparatively small residual component.

That is not what the data show.

This does not, on its own, prove a pre-Roman origin for metalworking at Bainbridge. However, it does undermine the assumption that metalworking activity was primarily generated by Roman military occupation. At the very least, it requires the possibility that the Romans encountered, formalised, or expanded an already active industrial landscape.

This interpretation aligns closely with other lines of evidence discussed earlier in this study: shallow non-defensive ditches consistent with drainage or water management, the absence of Roman road engineering approaching the site, and the site’s strong hydrological advantages. Together, these factors point toward an industrial function that is not dependent on Roman military logistics for its explanation.

Comparable patterns are well documented elsewhere in Britain, where Roman structures were imposed on pre-existing productive or ritual landscapes. Roman presence in such cases represents control, regulation, or enhancement — not necessarily origin. Bainbridge fits this model far more comfortably than that of an isolated fort built solely to house troops in a marginal location.

The key issue, therefore, is not that previous excavators were wrong to identify Roman-period activity. It is that the dominance of unphased industrial material was not interrogated as a question of origin, longevity, or pre-existing function. That omission matters, because it directly affects how the site is understood.

The metalworking evidence does not demand a pre-Roman interpretation. But it also does not support a purely Roman one. Any robust account of Bainbridge must therefore treat Roman occupation as part of a longer industrial sequence, rather than its beginning.

Chapter 9 — Why Roads Fail, and Rivers Don’t

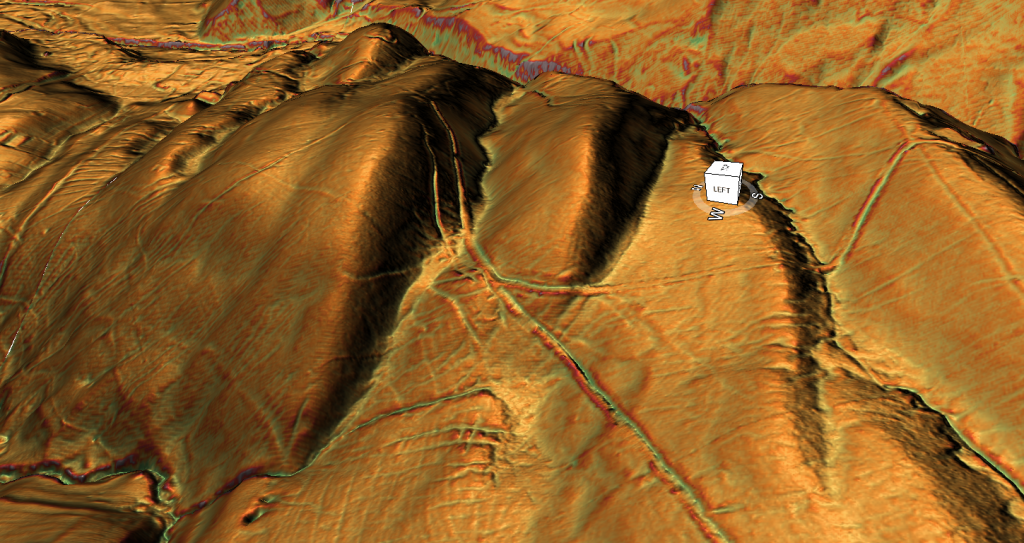

If Bainbridge were a conventional garrison fort, its logistics would be straightforward: roads in, roads out, carts supplying men and equipment. Yet this is precisely where the traditional model collapses. Once examined against the physical landscape, the assumption of a road-based supply system becomes increasingly implausible, while a river-based system explains the site with remarkable efficiency.

Roman roads are not subtle features. Even when badly eroded or ploughed, they tend to leave persistent traces: aggers, flanking ditches, straight alignments that ignore minor topography, and engineered river crossings. At Bainbridge, none of these elements can be demonstrated beyond the immediate interior of the fort. Proposed road lines exist largely as cartographic expectations rather than as engineered realities. When tested against LiDAR and satellite imagery, they dissolve into slope-following tracks, later hollow-ways, or nothing at all.

The absence of convincing road infrastructure is not a minor gap; it is a structural problem for the garrison narrative. A permanently occupied fort engaged in specialist production would require the regular movement of heavy materials: fuel, ore, semi-processed metal, and finished goods. Moving such loads repeatedly by cart over upland terrain without engineered roads would be slow, expensive, and inefficient. Roman administrators were many things, but inefficient logisticians they were not.

Rivers, by contrast, solve the problem immediately. Bainbridge sits above the River Bain, close to its confluence with the Ure, which in turn feeds into the Ouse and Humber system. This places the site within a navigable network that connects inland production zones to lowland distribution routes and coastal access. Water transport allows heavy materials to be moved in bulk with a fraction of the effort required on land.

This logistical logic aligns perfectly with the industrial evidence. Metalworking produces weight: slag, ingots, finished objects, and fuel residues. Coal, in particular, is bulky and inefficient to transport by cart in quantity. Rivers are the natural solution, and Roman industry elsewhere repeatedly demonstrates a preference for water-based logistics wherever possible.

Hydrology also explains the site’s location far better than any road-based model. The fort is not perched to command a route; it is positioned to access and control a water system. Its relationship to the river valley is functional, not incidental. The broad, shallow ditches discussed in earlier chapters then make sense as part of an integrated system managing water flow, access, and movement within this hydrological context.

The river model also resolves the question of isolation. Bainbridge looks remote only if one thinks in terms of roads and towns. In river terms, it is connected. The apparent remoteness is an artefact of later transport priorities, not of Roman ones. What seems peripheral today may have been central within a water-based economic network.

This perspective also reframes the military presence. Soldiers were not stationed here to police roads that barely existed; they were there to secure a nodal point within a riverine supply system, protecting valuable production as it moved through controlled channels. Roads, where they existed, were secondary connectors, not the backbone of the site’s operation.

The failure of the road model is therefore not an absence of evidence waiting to be filled, but a misapplication of expectation. Once roads are assumed, every faint linear feature becomes a candidate. Once rivers are recognised as primary infrastructure, the landscape begins to behave logically again.

By the end of this process, the contrast is stark. The road-based interpretation struggles to explain the site’s location, infrastructure, industry, and longevity. The river-based model explains all of them with fewer assumptions and greater consistency.

With roads removed from the centre of the story, and rivers restored to their proper role, Bainbridge emerges not as a misplaced fort, but as a deliberately positioned industrial and logistical hub within a managed hydrological network.

That realisation brings us to the final question: how did the traditional narrative survive for so long — and what does its failure at Bainbridge tell us about Roman Britain more broadly?

That is the subject of the final chapter.

Chapter 10 — When Assumption Replaces Science

The failure of the traditional interpretation at Bainbridge is not the result of missing data, poor excavation, or bad faith. It is the result of something more subtle and far more common: assumption hardening into orthodoxy. Once a site is labelled a “Roman fort”, every feature around it is quietly recruited into that story, whether it actually behaves like Roman military infrastructure or not.

At Bainbridge, the process is easy to trace. A fort was identified. From that point onward, roads were assumed to exist even when they could not be demonstrated. Ditches were assumed to be defensive even when their depth, profile, and placement made that function implausible. Industrial evidence was treated as incidental rather than central, because it did not fit the garrison template. Over time, the narrative became self-reinforcing, and the landscape itself stopped being interrogated.

What breaks that cycle here is not reinterpretation but measurement. Excavated cross-sections show shallow, broad ditches that cannot function as leg-breakers. LiDAR and satellite data confirm those dimensions across the wider landscape with sub-metre accuracy. Hydrology explains the form and placement of the features far better than defence ever could. And the industrial evidence — iron working, copper-alloy casting, and silver assaying — demands a model based on production, control, and logistics rather than patrol and warfare.

None of these strands are controversial in isolation. Roman industry is well documented. Roman use of river transport is well documented. Roman reuse of earlier landscapes is well documented. What is unusual is allowing all of those strands to override the comfort of a familiar label.

This is where Bainbridge becomes important beyond its own valley. If a site this well studied, excavated, and published can still be mischaracterised because interpretation was allowed to outrun function, then the same problem is likely repeated elsewhere. How many other “forts” are actually production sites? How many “defences” are actually infrastructure? How often has Roman presence been mistaken for Roman origin?

The excavation reports at Bainbridge never claimed final answers. They recorded what was found, within the limits of the methods available at the time. The error crept in later, when interpretation stopped being provisional. Modern tools now allow us to revisit those records, not to contradict them, but to finish the job they began.

Seen this way, Bainbridge is not an embarrassment to archaeology. It is a correction. It shows what happens when geometry, physics, hydrology, and excavation data are allowed to speak together, without forcing them into a predetermined story. The result is not a weakened history, but a stronger and more interesting one.

Bainbridge was not a misplaced garrison guarding nothing. It was a fortified manufacturing and logistics centre, embedded in a managed river landscape, probably formalising and securing a place that already mattered before the Romans arrived. The military presence was there to protect value, not to repel enemies. The ditches managed water, not attackers. The river moved goods where roads never did.

This conclusion does not diminish Roman Britain. It reveals it as more complex, more pragmatic, and more economically driven than the cartoon version we often repeat. And it reminds us of a basic rule that archaeology — like all sciences — ignores at its peril:

If the story does not match the ground, it is the story that must change.

The Romans did not create the industrial activity at Bainbridge; they encountered it.

Case Study: Testing the “Roman Road” Claim Against the Ground

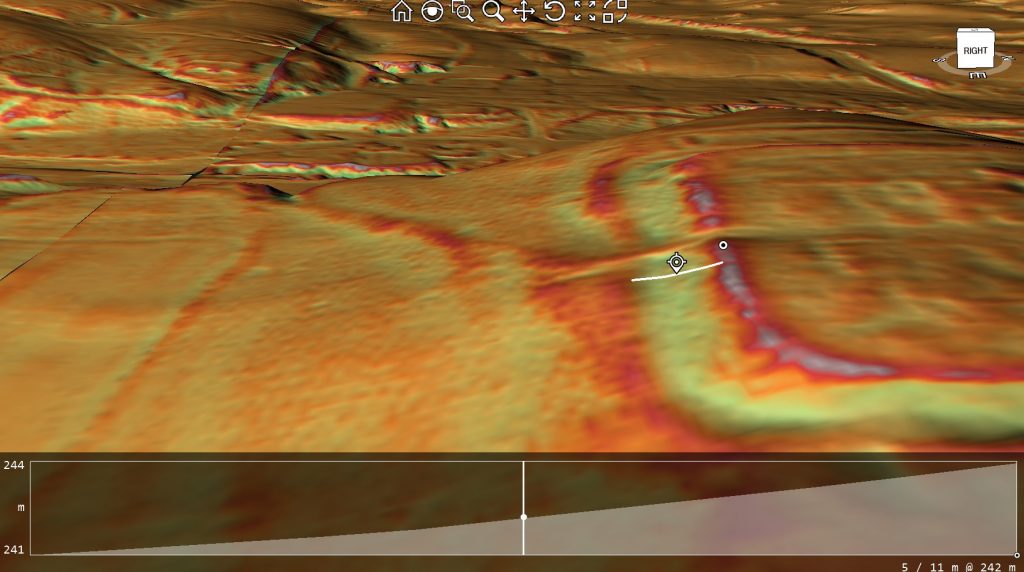

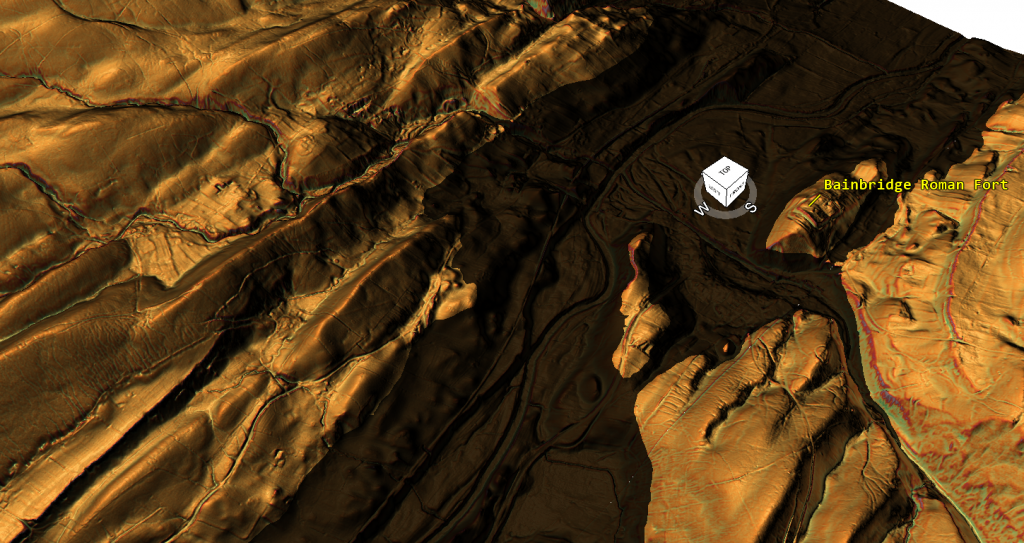

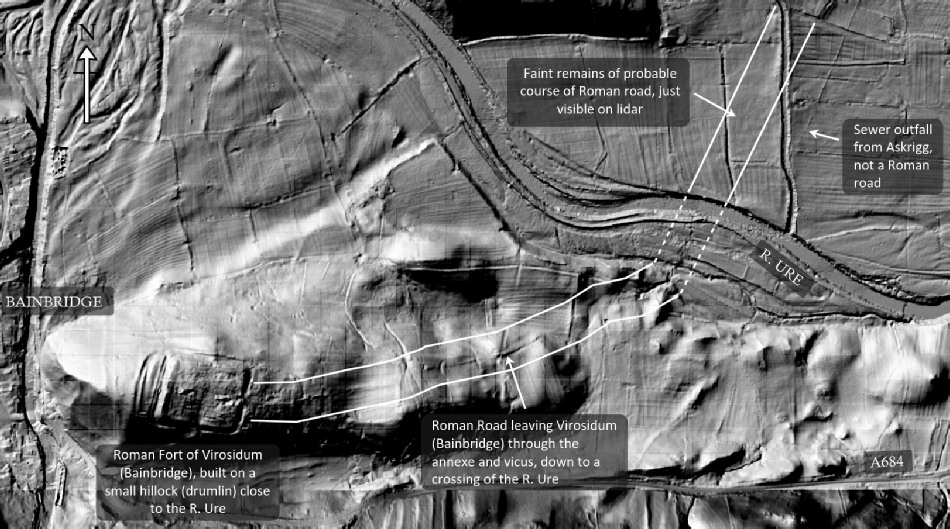

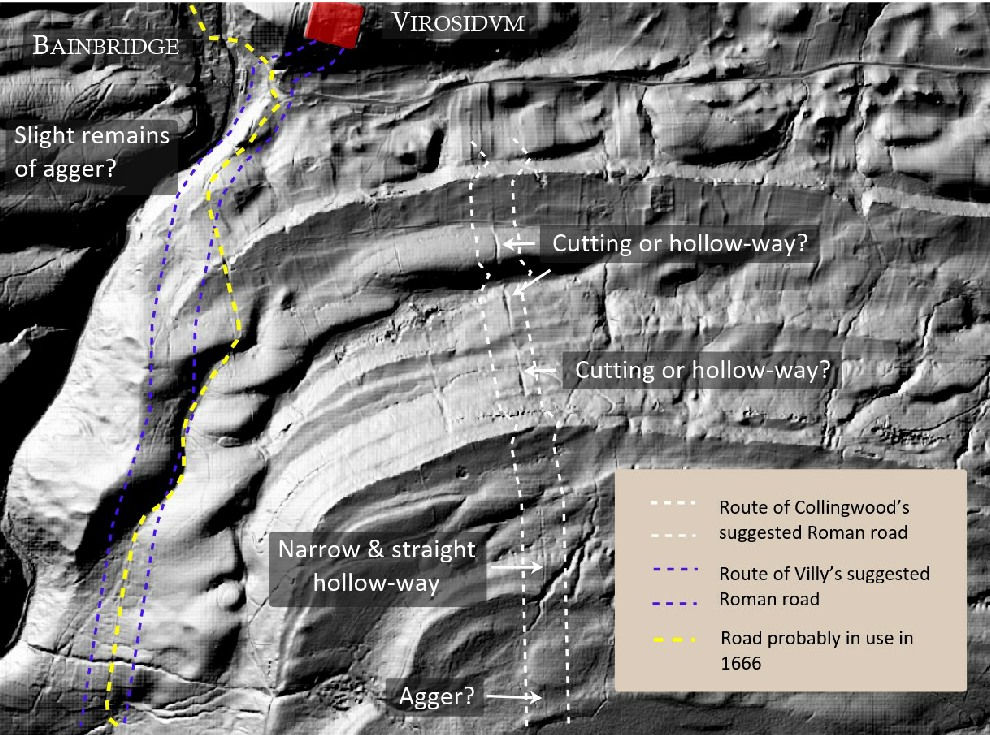

The LiDAR relief image above shows the southern approach to Bainbridge (Virosidum), viewed obliquely to expose slope behaviour, surface form, and constructional signatures. This image is the evidence.

At first glance, a linear feature appears to traverse the hillside and descend toward the valley. This line has been interpreted as the approach of Cam High Road to the fort. The key question is not whether a line exists, but whether the feature visible here behaves like a Roman-engineered road.

When examined carefully, the answer is no.

1. There is no agger visible in this image.

Roman primary roads are built on a raised embankment to provide drainage and structural stability. In oblique LiDAR views, aggers normally appear as continuous, slightly elevated ribbons that persist even under ploughing. In this image, no such raised platform exists. The surface remains flush with the slope, thinning and dissolving rather than standing proud. Where gradient increases — precisely where an agger should be most obvious — it disappears entirely.

2. There are no paired roadside ditches.

Roman roads are typically flanked by drainage ditches that define and protect the carriageway. These ditches often survive better than the road surface itself. In the LiDAR image, no parallel ditch system can be traced along the line of the supposed road. Instead, the feature merges into general slope wash and irregular cuttings, with no consistent boundaries.

3. The width is unstable and inconsistent.

Roman roads maintain a consistent carriageway width, typically around 5–7 metres. The feature visible here narrows, broadens, and fades unpredictably. In places it becomes a narrow hollow; elsewhere it fragments or vanishes. This behaviour is incompatible with engineered construction but entirely typical of routes formed gradually by repeated later movement.

4. The feature follows the contour rather than resisting it.

Roman engineers minimised gradient change by cutting through minor undulations rather than obediently tracing hillsides. In this image, the line hugs the slope, curving gently to accommodate terrain. That is the behaviour of a path chosen for ease of passage, not one imposed by survey and construction.

5. There is no engineered river approach or crossing.

The line descends toward the valley floor and reaches the river without any visible bridge abutments, causeway, revetment, or stabilised approach. Roman roads do not simply arrive at rivers and stop. Where crossings existed, structural traces normally persist in LiDAR and topography. None are present here.

What is visible in this image is entirely consistent with a hollow-way or slope-cut access route — a feature created by prolonged movement along the easiest available line. Such routes naturally align on entrances or landmarks, creating the illusion of deliberate planning when viewed from above. Alignment, however, is not evidence of Roman engineering.

Crucially, this interpretation does not rely on denying Roman presence at Bainbridge. It relies on recognising that Roman occupation does not automatically generate Roman roads, and that later and post-Roman movement can overwrite the landscape far more visibly than short-lived engineered surfaces.

The conclusion drawn directly from this image is therefore straightforward:

this is not a degraded Roman road. It is a slope-following access route that lacks every defining constructional characteristic of Roman primary road engineering.

This case study demonstrates a wider methodological issue explored throughout the blog. Once a site is labelled a fort, linear features nearby are often interpreted as roads by default. When those features are tested against constructional behaviour rather than visual alignment, the interpretation fails.

Here, the LiDAR does not show a Roman road in poor condition.

It shows the absence of one.

📌 What the Roads of Roman Britain (RR73) entry actually indicates

The Roads of Roman Britain entry acknowledges that:

the road heading south-west from Virosidum (Bainbridge) — often called Cam High Road — is treated as an exception among Roman road routes in the region. roadsofromanbritain.org

That wording is already significant: “exception” in this context means that it does not have the same evidential certainty as other documented routes.

The only formal source routinely cited for a Roman road connecting Bainbridge to the south-west is the Roads of Roman Britain gazetteer entry RR73. This entry is often treated as confirmation that Cam High Road reached the fort. A close reading shows that this confidence is not warranted.

RR73 does not present an excavated road, a confirmed road body, or any demonstrated Roman engineering on the ground. Instead, it catalogues a proposed route, assembled from alignments, historical references, and inferred continuity between better-attested road sections elsewhere. Crucially, the gazetteer itself treats RR73 as an exception rather than as a securely evidenced Roman road.

This distinction matters. In the Roads of Roman Britain project, well-attested roads are supported by one or more of the following: excavated metalling, identifiable aggers, paired roadside ditches, engineered river crossings, or consistent construction signatures traceable across the landscape. None of these are recorded for the supposed approach to Bainbridge.

There is no published excavation demonstrating a Roman road body on this alignment. There is no section showing metalling or agger construction. There is no evidence of an engineered crossing of the River Bain. The “road” exists only as a mapped hypothesis, not as an archaeological structure.

Even if RR73 represents a genuine Roman route elsewhere in Yorkshire, that does not demonstrate that it physically connected to the fort at Bainbridge. Roman roads do not terminate invisibly, nor do they abandon engineering precisely at valley descents and river crossings. Where roads entered forts, the connection is normally unmistakable in both excavation and topography. At Bainbridge, that connection is absent.

The significance of RR73, therefore, is not that it proves a Roman road reached Bainbridge, but that it exposes how easily inferred routes harden into assumed facts. The gazetteer records a possibility, not a demonstrated reality. Treating that possibility as evidence reverses the burden of proof.

Taken together with the LiDAR analysis presented above — the absence of an agger, lack of roadside ditches, unstable width, contour-hugging behaviour, and missing river engineering — the RR73 entry does not rescue the road hypothesis. It confirms that the connection between Cam High Road and Bainbridge is interpretive, not archaeological.

If a Roman road had genuinely approached the fort, a single excavation trench would have resolved the question decades ago. The fact that none exists is telling.

Smoking Gun: The Priests Bank Junction and the End of Cam High Road

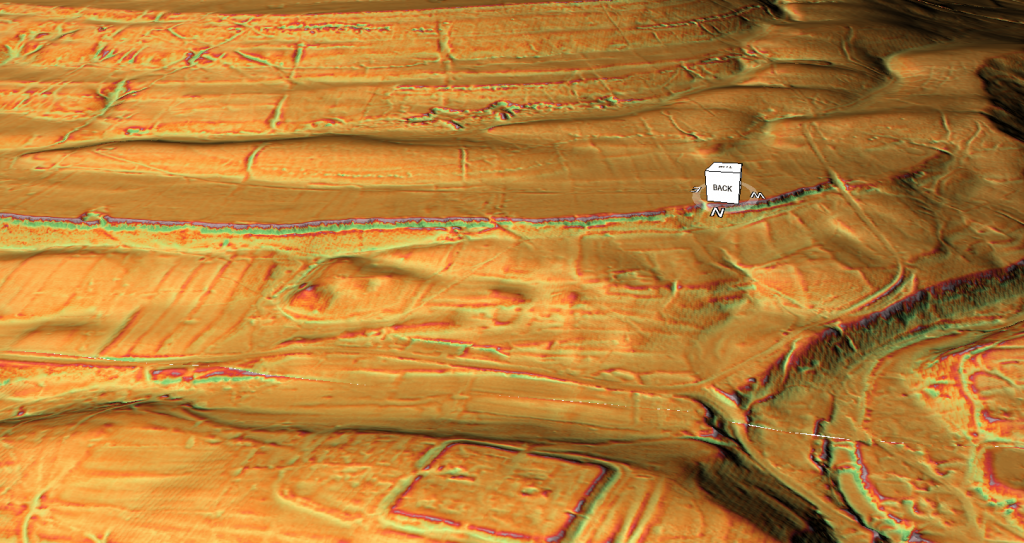

The junction at Priests Bank provides the clearest and most decisive evidence yet that the feature traditionally labelled Cam High Road did not function as the Roman road serving Bainbridge, and may not be Roman in origin at this point at all. Unlike alignment-based arguments, this conclusion is derived from physical interaction between earthworks, which allows relative dating and functional priority to be established directly from the ground.

As shown in the accompanying LiDAR relief graphic, the route identified as Cam High Road is physically cut by the Countersett road. The bank associated with Cam High Road continues on either side of the junction but is breached and truncated where the Countersett route passes through it. This relationship is unambiguous: the feature that is cut must be earlier, and the feature that cuts must be later. On morphological grounds alone, Cam High Road predates the Countersett road at this location.

From this junction onward, Cam High Road loses coherence and functional priority. One branch turns upslope and peters out into the hills; the other becomes increasingly indistinct. It no longer behaves as a through-route with a clear destination. By contrast, the Countersett road maintains continuity, direction, and purpose, forming the only route that demonstrably carries movement toward Bainbridge.

This geometry matters. If Cam High Road were the Roman arterial route serving a fort at Bainbridge, it would retain priority through the junction, with subsidiary routes branching away from it. What is observed is the opposite. Cam High Road becomes secondary and residual, while the Countersett route assumes the primary role in accessing the site. Bainbridge is therefore not the destination of Cam High Road.

The implications are decisive. Even if Cam High Road represents a genuine Roman route elsewhere, the junction at Priests Bank shows that it terminates functionally before reaching Bainbridge. The road that actually connects to Bainbridge is a different route altogether, one that intersects Cam High Road rather than extending from it. This finding aligns precisely with the absence of Roman road engineering on the approach to the site: no agger, no roadside ditches, no consistent carriageway, and no engineered river crossing.

This junction analysis resolves a long-standing assumption. The supposed Roman road serving Bainbridge has never been excavated, never been demonstrated as an engineered structure, and now can be shown not to connect to the site in functional terms. The idea that Cam High Road served the fort rests entirely on expectation rather than evidence.

In methodological terms, this is the critical point. Alignment can mislead; names can mislead; maps can mislead. Cutting relationships do not. At Priests Bank, the landscape itself records the sequence, and that sequence shows that Cam High Road is earlier, secondary, and irrelevant to access at Bainbridge.

This is the smoking gun.

Cam High Road does not serve Bainbridge.

And without a Roman road, the fort narrative collapses into something far more interesting: a site whose importance lies not in military logistics, but in landscape, hydrology, and long-term industrial use.

Podcast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?