📖 Stonehenge: The World’s First Computer

Free online access to the complete evidence-based reconstruction of Stonehenge’s original function

This page provides free access to the full book

The Stonehenge Computer,

which sets out a technical, testable model demonstrating that Stonehenge was originally constructed as a functional astronomical and hydrological calculation device, not a ceremonial monument.

The model presented here treats Stonehenge as:

- a working system

- built to track lunar cycles

- linked directly to tides, groundwater, and seasonal prediction

- embedded in a post-glacial flooded landscape

🛒 Available Formats

What This Book Examines

Stonehenge has been described for centuries, but rarely analysed as a machine.

This book asks a simpler question:

What does Stonehenge actually do?

By examining geometry, spacing, repetition, and landscape position, the book demonstrates that the earliest phase of Stonehenge functions as a computational device capable of tracking:

- the 56-year lunar cycle

- nodal extremes of the Moon

- predictable tidal amplification

- seasonal water-table behaviour

These are not symbolic alignments.

They are operational relationships.

The Core Components of the Stonehenge Computer

1. The Aubrey Hole System

The 56 Aubrey Holes are treated not as burial pits, but as a cyclic counting array, consistent with known lunar periodicities.

Their number, spacing, and enclosure geometry allow:

- long-term tracking of the Moon

- correction for drift

- repeatable prediction over generations

2. The Ditch and Moat

The ditch is analysed as a deliberately water-holding structure, not a defensive feature.

Its construction method, internal form, and sediment sequence are consistent with:

- retained water

- controlled seepage

- interaction with the groundwater table

Water is not incidental — it is integral to function.

3. Bluestones as Active Elements

Rather than passive symbols, bluestones are examined as:

- interactive components

- mineral interfaces

- elements within a hydrological system

Their fragmentation and distribution are consistent with use, not decoration.

4. Astronomical Geometry

The geometry of the enclosure, entrances, and station points is shown to encode:

- solar extremes

- lunar standstills

- repeatable observational baselines

No single alignment explains Stonehenge.

The system does.

Why the “Computer” Interpretation Matters

Treating Stonehenge as a ritual monument creates contradictions:

- unnecessary complexity

- excessive precision

- redundant features

Treating it as a calculation device resolves them.

A society living in a water-dominated post-glacial landscape would need:

- tidal prediction

- seasonal forecasting

- long-term calendrical stability

Stonehenge provides exactly that.

Method and Constraints

This book deliberately avoids:

- mythological interpretation

- symbolic speculation

- retrofitted ritual narratives

Instead, it applies:

- measurable geometry

- repeatable cycles

- landscape hydrology

- empirical constraints

If a feature has no functional role, it is treated as unresolved — not explained away.

Relationship to the Wider Research

The Stonehenge Computer builds directly upon the hydrological framework established in:

- Post-Glacial Flooding in Britain

That earlier volume defines the environmental conditions under which Stonehenge was constructed.

This book shows how those conditions were:

- measured

- monitored

- and engineered into stone

Who This Book Is For

- Readers dissatisfied with ritual explanations

- Researchers interested in early science and engineering

- Archaeologists working with astronomical or landscape data

- Anyone asking how rather than why

This book forms part of a wider evidence-led sequence:

- Post-Glacial Flooding in Britain

- The Stonehenge Computer

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

All are available via the online bookcase.

Podcast

The Videos

More Book information

Contents

Foreword

Robert John Langdon

Prologue — Why This Book Exists

Chapter 1 – Introduction: A New Breakthrough at Stonehenge

- Why existing explanations fail

- The problem Stonehenge presents

- What does “computer” mean in a prehistoric context

- Function versus symbolism

- Rules of evidence used in this book

- What will be proven, and how

Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase 1: 8300 BCE

- Separating Phase One from Later Reuse

- Why Later Monuments Must Not Shape Early Dating

- Dating Conflicts and Why They Exist

- What Phase One Was — and Why the Date Matters

- What Was Built — and What Was Not

- Why Phase One Must Be Understood First

Chapter 3 – Water, Flooding, and Why Prediction Mattered

- Post-glacial flooding as a measurable inland process

- Terrace geometry and Stonehenge’s elevation

- Floodplain width and water persistence

- Raised groundwater in chalk landscapes

- Stonehenge within the saturated floodplain system

- Risk, timing, and the cost of error

- Why does prediction follow inevitably

- The moat, the water table, and the need for tidal prediction

- Model of tidal behaviour

- Bluestones and mineralised water

- Phase 1 hydrology reconstructed

Chapter 4 – Construction, Sequence, and Operation of the Phase 1

- Phase 1 as a coordinated engineering project

- Bluestone arrival and functional integration

- Bluestones as information carriers and spatial memory encoding

- The Aubrey circuit is a fixed computational structure

- The single-marker operating principle

- How the one-marker system worked (step-by-step)

- Bluestone lifecycle: use, exhaustion, and replacement

- From construction to computation

Chapter 5 -The Aubrey Holes: Step, Scale, and the Bodies

- Human-scale construction as the controlling method

- Ten steps as a functional constraint

- One hundred steps across the circle

- Step length, biomechanics, and surveyor stature

- Numerical structure of Phase 1

- The Aubrey Holes as fixed records of human action

Chapter 6 – Stonehenge Phase 1 as a Predictive Subsistence System

- Integrated tide and moon modelling

- Stone height equals tide height

- The one-marker predictive system

- Why earlier astronomical models fail archaeologically

Chapter 7 – How the Model Works: Examples

- The Aubrey Hole Calculator

- Daily operation scenarios

- Tide and luminosity walkthroughs

Chapter 8 – Stonehenge Phase 2

- Hydrological decline and loss of mooring

- The engineering origin of the Avenue

- Ditch engineering and groundwater failure

- Clay lining and artificial water retention

- From water engineering to stone engineering

Chapter 9 – Why the Monument Changed

- Doggerland, cultural rupture, and monumentalisation

- Phase II orientation and the Doggerland axis

- The Slaughter Stone is an island map

- Why do humans build with stone

- Phase II as a cenotaph and memory architecture

Chapter 10 – How Phase II Was Set Out

- Setting out the monument

- Solstice alignment and dating

- The hexagram construction

- The role of equilateral triangles

- Crescent form and trilithon placement

- The hexagram encountered, not invented

- Belief System (Reframed): Why Six Matters

Chapter 11 – Number, Measure, and Construction

- The mind of the builders

- Embodied geometry

- The body was fixed in the ground

- Phase II geometry and scale continuity

Chapter 12 – Number, Division, and the Emergence of Twelve

- Measurement produces counting

- Six as a geometric outcome

- Sixty as a working number

- Twelve as a practical subdivision

- Anatomical origins of duodecimal systems

Chapter 13 – Dispersal of the Duodecimal Tradition

- Where duodecimal systems persist

- Mesopotamia

- Egypt

- Indus Valley

- Mediterranean survivals

- Why decimal eventually dominates

Chapter 14 – What Stonehenge Preserves

- What has been demonstrated

- What Stonehenge is — and is not

- Why Stonehenge matters

- The broader implication

References

Authors’ Biography & Other Books

Social Media Contributions and Links

Technical Analysis of Stonehenge Phase 1 as a Prehistoric Analogue Computer for Tidal Prediction

1.0 Introduction: A Functional Reassessment of Stonehenge

For centuries, Stonehenge has been perceived primarily as a symbolic or ritualistic monument. This paper reframes that perspective, presenting a functional model of Stonehenge Phase 1 as a piece of precision-engineered infrastructure: a working analogue computer. Through a systems analysis of its physical components, operational logic, and environmental context, we will demonstrate that the monument’s earliest form was a sophisticated tool designed to solve a critical survival problem for its builders. This analysis presents a methodological challenge to conventional archaeology, prioritising systems engineering and functional necessity over narrative symbolism.

The prevailing archaeological models—which alternately cast Stonehenge as a temple, an astronomical observatory, or a cemetery—ultimately fail because they cannot account for all of the site’s primary features simultaneously without contradiction. A temple does not require a precision counting system with built-in error correction; an observatory does not depend on variable stone heights or a permanent water feature; and a cemetery does not actively process and remove the dead. These models are mechanically incoherent because they prioritise presumed meaning over demonstrable function.

This analysis defines the term “computer” within its appropriate prehistoric, analogue context. It describes a system that uses repeatable physical operations to transform known inputs into useful predictions. Information is not stored abstractly but is encoded physically in the height of a stone, the depth of a hole, or the position of a marker. Operations are carried out not through calculation but through disciplined, sequential movement.

To accurately assess this system, it is methodologically essential to separate the original construction of Phase 1 from its later reuse and modification, a date established by a powerful statistical convergence of radiocarbon evidence to c. 8300 BCE. The historical practice of blending different construction phases has created a composite, confusing narrative that obscures the monument’s original purpose. By isolating Phase 1, its coherent internal logic becomes clear. This paper will show that the design of the Stonehenge computer was a direct and intelligent response to the specific environmental and operational needs of its time.

2.0 System Requirements: The Post-Glacial Hydrological Problem

To understand the design of the Stonehenge computer, one must first understand the strategic environmental context of Britain around 8300 BCE. The system’s architecture was not arbitrary; it was a direct response to the profound survival challenges posed by a post-glacial, water-dominated landscape. This environment created the specific “problem” that the Stonehenge system was engineered to solve.

During the early Holocene, the chalk landscape of southern Britain was characterised by extremely high groundwater levels. An analysis of the River Avon’s terrace geometry reveals a floodplain that was dramatically wider than today, extending up to 10-12 kilometres across the valley floor. The elevation of Stonehenge, at 102-103 meters Ordnance Datum (OD), places it directly within the vertical envelope of this sustained floodplain activity. This was not a landscape with a river running through it; it was a saturated, hydraulically active, and fundamentally unstable environment.

In such a world, the ability to predict tidal cycles was a critical survival requirement. Navigating the expanded river systems, accessing coastal and estuarine resources, and safely traversing the landscape depended entirely on anticipating changes in water levels. A miscalculation could mean being cut off, losing access to food sources, or being caught in dangerous currents. The primary operational requirement, therefore, was a reliable method for tidal prediction.

The Phase 1 ditch was a direct answer to this environmental context. Excavated deep enough to intersect the chalk aquifer, it was not a symbolic boundary but a self-regulating moat designed to hold permanent water. It transformed a volatile external feature—water—into a controlled internal component of the system. However, it is crucial to distinguish between the co-located systems at the site. The predictive computer, comprised of the Aubrey Holes and bluestones, does not require a body of water to operate. The moat, instead, reflects a parallel exploitation of the hydrological conditions for other purposes, such as healing and resource management. This understanding of distinct yet integrated functions provides the necessary context for analysing the predictive tool’s physical architecture.

3.0 System Architecture: Physical Components and Information Encoding

The Stonehenge Phase 1 computer was constructed from a set of carefully engineered physical components, each serving a distinct role in the system’s computational function. This section deconstructs the system’s “hardware,” detailing how each element—from the precisely arranged holes in the ground to the imported stones and earthen barrows—contributed to its ability to model and predict environmental cycles.

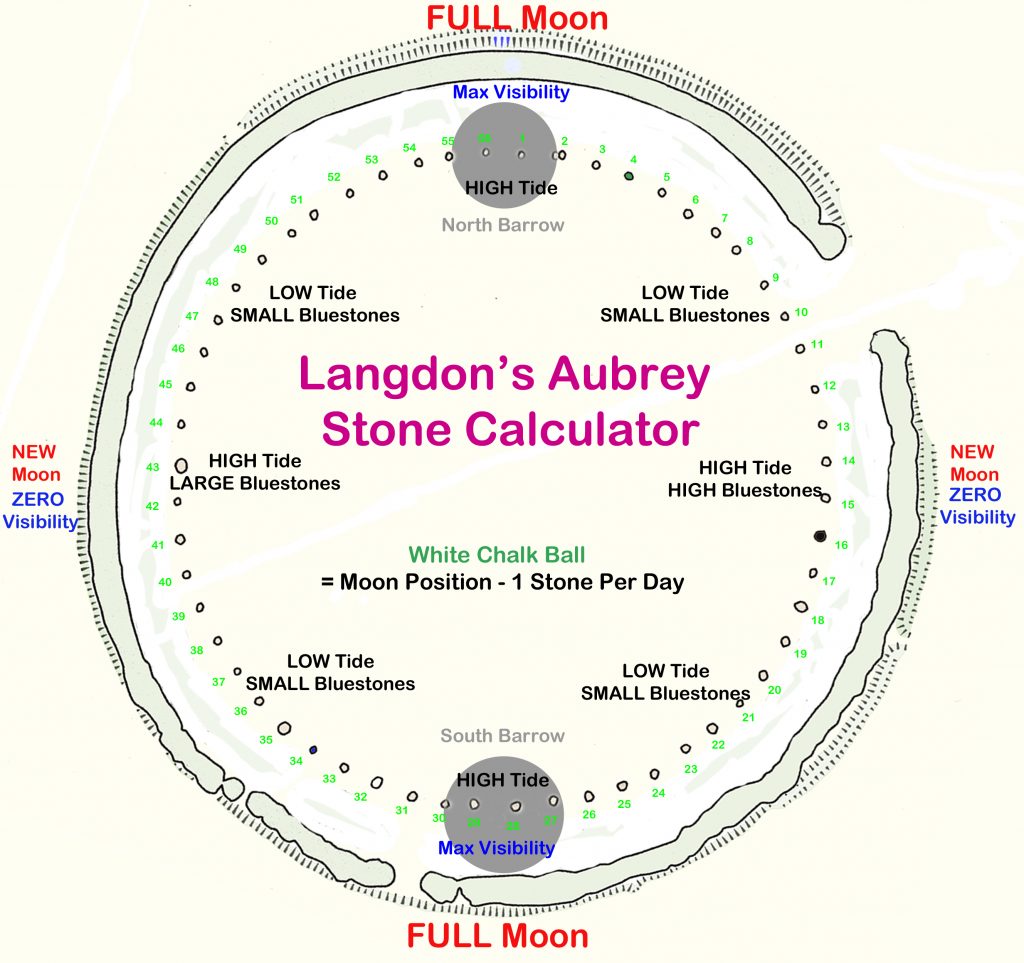

3.1 The Aubrey Hole Circuit: The Data Structure

The core data structure of the computer is the ring of 56 pits known as the Aubrey Holes. The selection of 56 positions is functional, not symbolic. It provides a perfect register for modeling two complete 28-day spring-neap tidal cycles, allowing for a planning horizon of nearly two months without fractional drift.

Physical analysis of the holes reveals that their dimensions are not uniform. The size and depth of the holes vary systematically around the circuit, embedding a permanent tidal amplitude curve directly into the ground. Larger, deeper holes, which would be required to support taller, heavier stones, correspond to positions of peak tidal amplitude (spring tides). Conversely, shallower holes are found at positions corresponding to the weakest tidal periods (neap tides). The circuit is therefore not merely a set of counters but a fixed, analogue memory that stores the fundamental pattern of tidal behaviour.

3.2 The Bluestones: Physical Information Encoding

The bluestones served a dual function as both information carriers and material resources. Their primary computational role was to encode the expected tidal amplitude for a given day. The variable heights of the bluestones placed in the Aubrey Holes provided a direct, visual read-out of the system’s prediction: a taller stone represented a stronger tide, while a shorter stone indicated a weaker one. This method of analogue encoding translated an abstract variable (tidal strength) into a tangible physical attribute that could be understood without calculation or literacy.

Secondly, the mineral-rich bluestones were used to condition the water held in the surrounding ditch. Positioned in a direct hydraulic relationship with the moat, the stones would gradually leach trace elements into the water, creating a stable, mineralised body of water likely used for healing or ritual purposes. The archaeological evidence of bluestone fragmentation, reuse, and replacement points to a systematic lifecycle of resource management, where stones were used, became chemically exhausted, and were subsequently processed and replaced. This view of the monument as a dynamic system with consumable parts reinforces the infrastructure-and-machine analogy, moving it away from the conception of a static, unchanging monument.

3.3 The Moon Barrows: Signal Amplification

The North and South “Moon Barrows“—earthen mounds integrated directly into the Aubrey circuit—functioned as a physical amplification mechanism. Because portions of the Aubrey Hole ring pass over these raised barrows, stones of identical height would appear visually taller when placed on them. This differential elevation was used to represent periods of heightened operational significance related to lunar illumination. By physically amplifying the height of the stones at key points in the cycle, the system could visually flag conditions where both tidal forces and night-time light levels were at their most extreme, providing crucial information for fishing and navigation.

This combination of components created a static architecture capable of storing and displaying complex environmental data. The next section explains how this system was operated dynamically to produce daily predictions.

4.0 Operational Protocol: The Single-Marker Algorithm

Despite its architectural complexity, the Stonehenge Phase 1 computer was operated using a simple, robust single-marker algorithm. The system’s design prioritised operational clarity and minimised the potential for human error, making it suitable for a non-literate society where procedural knowledge had to be transmitted across generations. This section provides a step-by-step analysis of the computer’s daily operation.

The system’s single movable component, or “pointer,” was a flat-based chalk ball. Examples of these artefacts have been recovered from the site. The design was entirely functional: chalk was a locally available and easily replaceable material, while the flattened base prevented the marker from rolling, ensuring unambiguous placement at a specific position.

The daily operational procedure was straightforward and required no specialised calculation:

- Initialisation: The cycle begins on the day after the full moon. The operator places the chalk ball at the designated starting position, LH1 (Lunar Hole 1), located on the North Moon Barrow.

- Daily Iteration: At each subsequent sunrise, the operator moves the marker forward by one stone/position along the Aubrey Hole circuit.

- Data Read-Out: The predicted tidal amplitude for that day is read directly from the height of the stone at the marker’s current position. A taller stone signals a stronger tide, providing actionable information for that day’s activities.

- Looping: The marker proceeds sequentially through all 56 positions, modelling two complete 28-day tidal cycles before returning to the start to be reset at the next full moon.

The efficiency of this one-marker system stands in stark contrast to the fragile multi-marker models proposed by researchers like Hawkins and Hoyle to explain Stonehenge as an eclipse predictor. The tidal model succeeds where eclipse models fail because it accounts for the physical evidence of variable stone and hole sizes, a key feature that purely abstract eclipse models cannot explain. The single-marker design of the tidal computer is operationally resilient, minimises the cognitive load on the operator, and simplifies the process of knowledge transmission. From this simple, repeatable operation, we turn to the system’s methods for handling errors and ensuring its long-term reliability.

5.0 System Robustness and Error Correction

For any piece of functional infrastructure, reliability and fault tolerance are critical design features. This is especially true in a prehistoric context, where the survival of a community could depend on the accuracy of its predictive tools. The Stonehenge Phase 1 computer was engineered with an inherent and exceptionally robust error-correction mechanism that ensured its long-term operational integrity.

The system’s primary reset mechanism was tied to a visually unmistakable astronomical event: the full moon. If the operator ever lost count, was interrupted, or made a mistake while moving the marker, any accumulated error or drift could be corrected immediately and completely. The operator simply had to wait for the next full moon and, on the following morning, reset the chalk ball marker to the designated starting position at LH1.

This method of error correction is exceptionally robust for several key reasons. First, it prevents errors from accumulating beyond a single lunar cycle. Unlike more complex computational systems where a small error can compound over time, this design ensures that the system is reset to a known correct state at least once per month. Second, it requires no specialist knowledge of the system’s underlying astronomical or mathematical principles. Any user could perform the reset, ensuring that the computer could be maintained across generations and withstand interruptions in its use without losing accuracy. This simple yet powerful reset protocol highlights a design philosophy focused on practical, long-term functionality.

6.0 Construction and Implementation: Human-Scale Engineering

The construction of Stonehenge Phase 1 was an act of precision engineering. However, this precision was not achieved through the use of abstract standard units or advanced mathematics. Instead, it was the product of a disciplined, repeatable process based on human-scale measurement, with the monument’s key dimensions resolving into whole-number multiples of a long human step.

Analysis of the monument’s layout reveals a coherent construction logic based on a step length of approximately 0.83–0.86 meters. The builders appear to have used their own bodies as measuring instruments, achieving accuracy through counted repetition and careful closure correction. The core geometric relationships of Phase 1 can be expressed in these human-scale terms:

| Geometric Element | Dimension in Human Steps |

| Ditch Inner Edge to Aubrey Ring | 10 steps |

| Aubrey Ring Diameter | 100 steps |

| Aubrey Ring Radius | 50 steps |

| Total Working Radius (Center to Ditch) | 60 steps |

| Average Aubrey Hole Spacing | 6 steps |

The 10-step dimension separating the Aubrey Ring from the ditch is not arbitrary but a functional optimum. It represents the ideal distance for mineral-rich water from the bluestone bases to leach laterally through the chalk aquifer and condition the water in the moat, a process dictated by hydrology and bluestone chemistry. This step-based methodology is further supported by a single, approximately 5-step interval between two of the Aubrey Holes. This feature acts as a closure correction, where a small cumulative error from pacing out the circle is absorbed in the final section. This is a definitive signature of construction by pacing, rather than by the abstract geometric subdivision of a circle.

Furthermore, the implied step length provides insight into the surveyor’s physical stature. Based on modern gait studies, a step of this length corresponds to a tall population, with individuals standing approximately 1.85–2.02 meters (6’0″ to 6’8″) in height. The monument’s precision is therefore a direct and legible record of disciplined human action, providing the final piece of evidence for this comprehensive functional model.

7.0 Conclusion: The Functional Specification of a Prehistoric Computer

This analysis systematically deconstructs Stonehenge Phase 1, presenting a coherent model that accounts for its environmental context, physical architecture, operational protocols, and construction methodology. The evidence demonstrates that the monument, in its earliest form, is best understood not as a place of ambiguous ritual, but as a functional analogue computer designed to solve a critical environmental problem for its Mesolithic builders. It was precision infrastructure, engineered for reliability and built to endure.

The core specifications of this prehistoric computational system can be summarised as follows:

- Purpose: Predictive modelling of lunar-tidal cycles for subsistence and navigation.

- Data Structure: A 56-position circular register (the Aubrey Holes).

- Information Encoding: Analogue representation of tidal amplitude via variable stone heights.

- Operational Method: A single-marker, daily-iteration algorithm.

- Error Correction: An inherent, visually-cued full moon reset protocol.

By prioritising function over symbolism, this model resolves long-standing archaeological paradoxes—such as the requirement for precision without writing, the functional purpose of variably sized holes, and the systematic processing of bluestones—that narrative and ritual models leave unanswered. Stonehenge Phase 1 ceases to be a mystical enigma and should be recognised as one of the earliest surviving examples of applied systems engineering—a testament to the sophisticated cognitive and technical capabilities of prehistoric societies in solving complex, real-world problems.

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?